The Inventor Of Aerosol Spray Destroyed The Ozone Layer. Here's How We Fixed It

In 1929, Norwegian scientist Erik Rotheim patented a way to distribute liquids via an aerosol can for the first time in history. Despite Rotheim's efforts, however, this invention never resulted in a profitable product for Alf Bjercke, the lacquer manufacturer that helped Rotheim develop the patent. Bottle production was prohibitively expensive, and the dimethyl ether gas that Rotheim had used as the propellant needed to make the spray can concept work was dangerous.

It wasn't until William Sullivan and Lyle Goodhue, researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, developed a working aerosol dispenser using chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gas that aerosol cans began to take off in earnest. Patented in 1941, their design came about as the result of the pair working on a solution to help U.S. troops combat insect-borne disease during World War II. Their design was so successful that manufacturers like Westinghouse Corporation sold tens of millions of the spray cans to the U.S. Armed Forces over the course of the war. By the 1970s, CFC-powered aerosol cans, air conditioning, and refrigeration systems were everywhere.

But the phenomenal success and celebration of these aerosol cans would be relatively short lived. In 1974, researchers Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina published groundbreaking findings about CFCs that forever altered the spray can industry, changed how humanity saw its relationship to the planet and the environment, and ultimately led to the two winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995.

CFCs destroyed the ozone layer

Published in Nature, Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina's research linked CFCs to the depletion of Earth's ozone layer. Initially utilized for their stability and nontoxic properties, CFCs were found to float up and eventually break down under ultraviolet (UV) light in the stratosphere, releasing chlorine atoms that destroy ozone molecules.

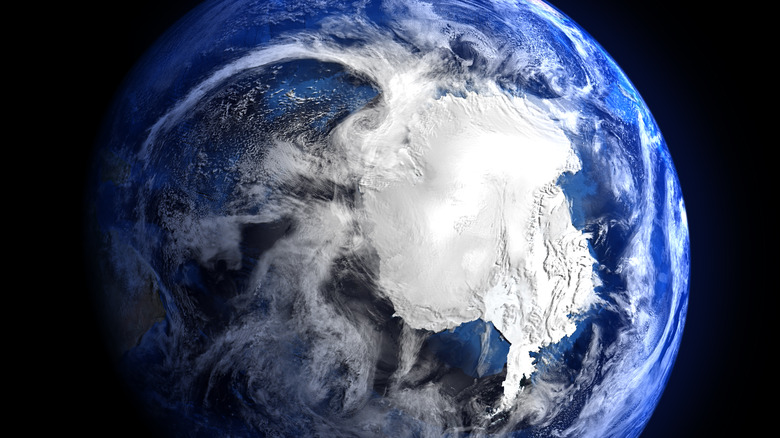

These findings were alarming. The Earth's ozone layer functions as the planet's natural shield against harmful UV radiation, exposure to which can lead to increased rates of skin cancer, cataracts, and even the disruption of marine ecosystems. Unsettlingly, the two were proven right in 1985 when scientists working with the British Atlantic Survey discovered a massive hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica. The imminent danger this presented, especially to countries in the Earth's southern latitudes, was clear. What followed was an unprecedented coming together of global policymakers and the scientific community that set in motion one of the most ambitious environmental efforts in history.

The response to the ozone crisis culminated in the Montreal Protocol, which was ratified in 1987. The landmark multilateral treaty called for the gradual phase-out of over 100 ozone-depleting substances, including CFCs, setting strict targets that all 197 countries on the planet agreed to follow. The protocol now includes several amendments that expand the list of controlled chemicals it addresses and reiterates the urgency of phasing out their production. To this day, the Montreal Protocol remains the most widely adopted environmental agreement in history.

A lesson for tackling climate change

The protocol's results have been nothing short of astounding. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, approximately 99% of ozone-depleting gases have been phased out of use. Because ozone is a naturally occurring substance, the Earth's UV radiation shield has been slowly "healing" since the agreement went into effect. Scientists expect the ozone layer over the Antarctic to return to pre-1980s levels by the 2060s.

Ozone-depleting substances also help drive global temperatures higher, so the fact that the ozone layer is repairing itself is welcome news. At a time when climate change threatens the natural systems that human civilization depends on for its survival, the story of the ozone layer's recovery is a potent reminder of what humanity can achieve when science and policy align for a common goal. As we face the current climate crisis of rising temperatures, biodiversity loss, and increases in the frequency of natural disasters, the success of the ozone recovery effort offers hope and a blueprint for addressing global warming.