How Long It Would Really Take To Get To Jupiter On Our Fastest Manned Rocket

This history of human spaceflight is remarkably short. Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space when he circled the Earth aboard Vostok 1 in 1961. The next big step forward came in 1965 when Aleksey Leonov stepped out of the Voskhod 2 craft, performing the first spacewalk. That same year, Gus Grissom and John Young were the first to change their orbit while in flight aboard Gemini 3.

These firsts were all just a prelude to the Apollo missions which took us to the moon. In 1968, Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders were the first to leave low Earth orbit on their trip to the moon on Apollo 8. Less than a year later, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin would take their historic first steps on the surface of the moon.

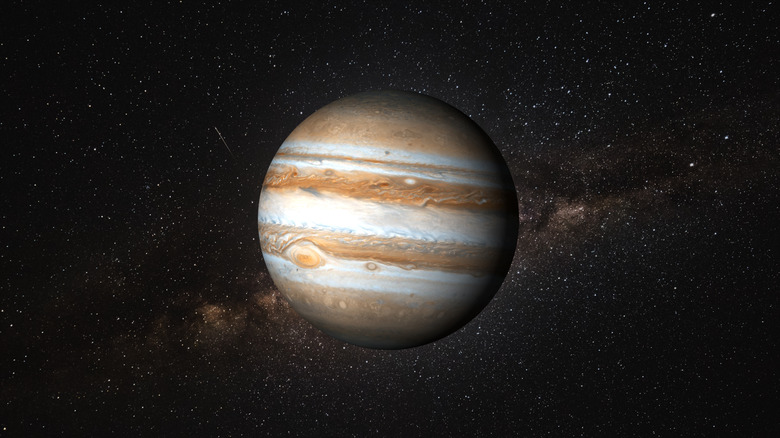

Now that NASA's going back to the moon (hopefully in 2026), it also has its sights set on getting to Mars sometime in the 2030s. Beyond Mars, the next target in the solar system is Jupiter, although there probably won't be any manned flights to the king of the planets before the 2070s. But if it were to be done, how long would it take, and what route would one need to travel?

How do you get to Jupiter?

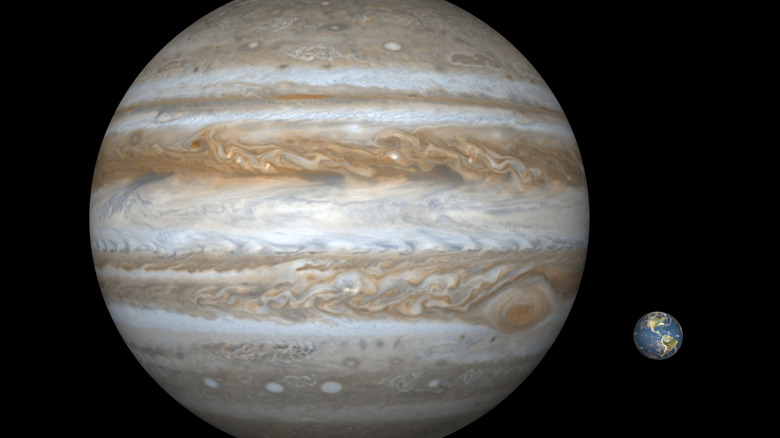

At its closest, Jupiter is over 1,500 times further away from Earth than the moon is: a whopping 365 million miles. Traveling at 24,816 mph (the fastest humans have ever gone), that trip would take about 613 days, but traveling in space isn't as straightforward as traveling here on Earth.

For one thing, Earth and Jupiter are always moving, so timing the window of departure is critical: You need to make sure Jupiter will be there when you arrive. You also have to take into account that any spacecraft sent to Jupiter will also be orbiting the Sun. In other words, you can't fly in a straight line to Jupiter.

Further complicating matters is the fact that you need a lot of fuel to get around in space. There's no wind resistance to slow you down, for one thing, so for every ounce of fuel you burn to go forward, be prepared to burn another ounce to slow down. That means that you're going to have to find a way to get there that burns the least amount possible. Fortunately, Walter Hohmann figured that out back in 1925.

How long will it take humans to travel to Jupiter?

Walter Hohmann developed something now called the Hohmann transfer orbit, an idealized transition from the orbit of one planet to another that uses as little fuel as possible. The general idea is to find the smallest orbit possible between the orbit you're launching from (Earth) and the orbit you're launching to (Jupiter).

The time it takes to make that trip is roughly equal to half of the average of the times it takes each object to orbit the sun. Jupiter orbits the sun every 4,333 days, and Earth orbits every 365 days. That comes out to a one-way trip of 1,174 days, or a bit over 3 years.

Because the two planets have to be precisely aligned for this to work, you'll only get a chance every 13 months thanks to the 398.88 day synodic period (a measure of relative positions, generally speaking). And this window works both ways. You'll have to stay on Jupiter long enough for this window to open up again before you could come home using this optimized route.

Haven't we already been to Jupiter?

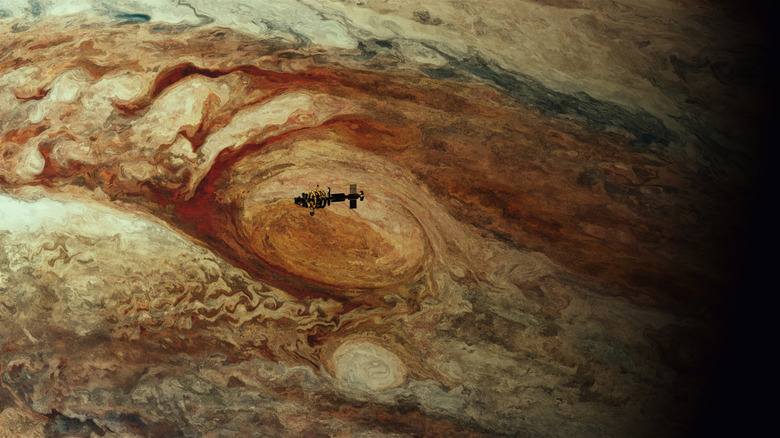

Even though a human has never traveled to Jupiter, humanity has sent a total of 11 robotic missions into the outer solar system that have visited the massive gas giant. Six of those missions merely passed through the Jovian system on their way to somewhere else, the fastest of which, New Horizons, reached Jupiter in a mere 405 days.

As for the other four missions, their path to Jupiter is a bit more circuitous. Whereas the flyby missions didn't have to stop, these orbital missions would have to have enough fuel to stop when they got there, meaning high speed wasn't really an option. The Galileo mission, launched in 1989, got a boost from Venus before doing a Hohmann transfer to arrive at Jupiter after six years. NASA's latest mission — Europa Clipper — launched in October 2024 and will take a similar path as Galileo, but instead of relying on Venus for a gravity assist, it will pick up extra speed from Mars, then Earth, before heading off to Jupiter. Europa Clipper is expected to take a bit under six years to arrive.

NASA takes these longer paths for its unmanned missions because it saves fuel that is needed to slow down on arrival at Jupiter. Humans, who are notoriously reliant on food to survive, will need to take a shorter path than their robot predecessors.