Fool's Gold In New York Actually Hid A Surprising Treasure

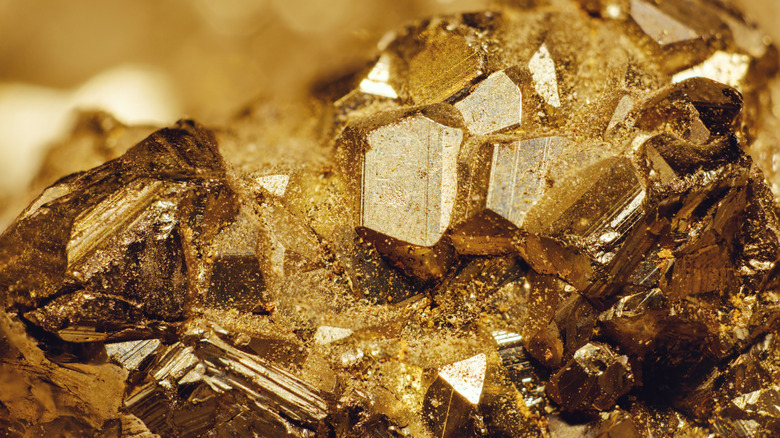

Sometimes, there's more to iron pyrite than meets the eye. While testing it to differentiate between fool's gold and real gold, it's possible to find tiny amounts of real gold inside. And that's not all. Scientists have discovered a new prehistoric arthropod impeccably preserved in iron pyrite specimens found near Rome, New York, in a fossil-rich spot called Beecher's Trilobite Bed.

In findings published in the Current Biology journal, the researchers describe seeing the anatomy of the creature. They used computed tomography to capture thousands of X-ray images of the specimens, which were likely immortalized in a submarine landslide. The scans were possible because the iron pyrite preserved the animal in three dimensions. What was inside was an arthropod that lived on the bottom of the ocean some 450 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. It has been named Lomankus edgecombei in honor of Greg Edgecombe, an arthropod expert at the Natural History Museum in London.

Lead author Luke Parry, an associate professor in the University of Oxford's Department of Earth Sciences, told CNN, "Preservation in pyrite of this kind is extremely rare. In the last half a billion years there are only a handful of examples of places where this occurs." The reason is that the soft tissues of arthropods usually decay before preservation.

What researchers know about the Lomankus edgecombei

As an invertebrate animal, the Lomankus edgecombei is part of the arthropod umbrella of creatures that includes centipedes, crustaceans, millipedes, and spiders. It belonged to the extinct megacheiran subgroup, which lived 485 to 538 million years ago during the Cambrian Period and had large appendages on the front of its body for catching prey. In keeping with why scientists study fossils, this newly discovered species could provide insight into how these appendages evolved on their heads.

The CT images captured of the Lomankus edgecombei allowed the researchers to create a three-dimensional reconstruction of the creature, but it's not the typical prehistoric sea animal that fuels nightmares. Instead, it more closely resembled shrimp as we recognize them today. It didn't have eyes, and its frontal appendages were less pronounced than those of megacheirans, so it likely felt its way around with them rather than use them to catch prey. Also, it had mouthparts or antennae similar to that of modern spiders or scorpions.

"Rather than representing a 'dead end', Lomankus shows us that megacheirans continued to diversify and evolve long after the Cambrian, with the formerly fearsome great appendage now performing a totally different function," Luke Parry explained in a press release. Co-author Yu Liu, a professor at Yunnan University in China, added, "This is a very similar arrangement to the head of megacheirans from the early Cambrian of China except for the lack of eyes, suggesting that Lomankus probably lived in a deeper and darker niche than its Cambrian relatives."