Major Scientific Discoveries That Happened By Accident

When we think of the great inventors and scientists of the past, it's easy to imagine them tinkering away in their lab or poring over their diagrams until their skilled deductions finally result in them hitting the jackpot. However, with many of the most significant inventions of recent centuries, there was more than a little serendipity involved.

From pacemakers created due to the wrong resistor, to post-it notes made from failed adhesives, it was often a scientific failure that led to an amazing discovery. Accidental science is testament to the idea that curiosity and a willingness to learn from your mistakes will get you far, as these inventors have all proven. Sure, without the chocolate bar in Percy Spencer's pocket he may not have started his work on the microwave oven when he did, but his determination and resilience may well have got him there eventually. Join us as we explore the fascinating stories behind the inventions that very nearly weren't, and marvel at the amazing technology that has come about by accident.

Penicillin

As Scottish scientist Alexander Fleming left his lab to go on a two-week vacation in 1928, he couldn't possibly imagine that what he would return to would change the face of medicine forever. He had been working with Staphylococcus bacteria before his departure, and on arriving back to the lab, was shocked to find that mold had made its way onto the petri dish, and it had prevented the bacteria from spreading.

Like many of the discoveries on this list, the significance of Fleming's accidental experiment wasn't fully appreciated by the scientific community at the time. Fleming continued his research with help from a small group of chemists, but they were unable to isolate the drug from the mold. It was more than a decade before penicillin as a drug was created, and the success of animal trials meant the scientific world began to take it seriously.

The scaling of production of penicillin from lab to mass market took off in America during the Second World War, and it allowed for the successful treatment of infections that would previously have proved fatal. Alexander Fleming won the Nobel prize for Medicine in 1945, and antibiotics went on to save more than 200 millions lives since then. If Fleming had been a bit tidier and cleaned up his experiments before he went on holiday, who knows how long the power of penicillin would have remained a secret?

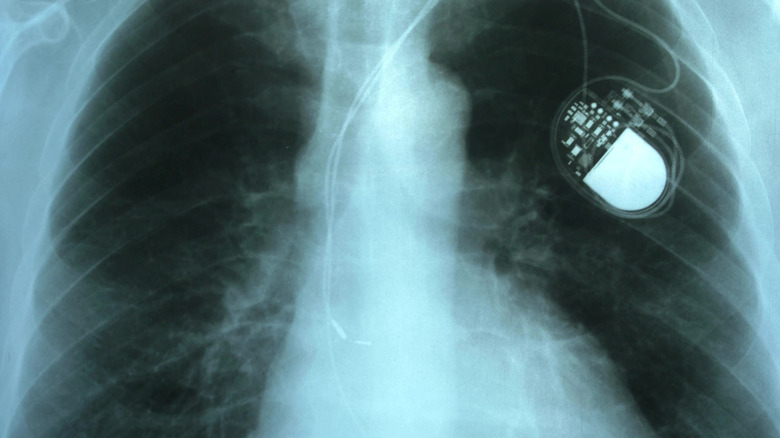

Pacemaker

Wilson Greatbatch was an American electrical engineer working in medical research in 1956, when he made a mistake that would change his career — and medicine — forever. He was attempting to build a device that could record heartbeats, but he used the wrong resistor, installing a 1 megaohm component instead of a 10 kiloohm one. Instead of recording the sound of a heartbeat, it produced pulses of its own instead, in a steady, rhythmic beat. Greatbatch instantly realized what this could mean, and he set about creating the first truly portable pacemaker.

Most existing pacemakers leading up to this time were portable only in the sense that they could be unplugged to be moved to another room, then plugged back into the mains. The concept of a pacemaker that would allow the patient to move around freely was revolutionary.

After a few years of development, Greatbatch's invention was installed in its first human patient in 1960, curing his heart block in a way that had never before been possible. Later, Greatbatch also invented the long-life lithium battery that would power the pacemakers for longer. His accidental discovery and subsequent invention was honored in the 1980s when the wearable pacemaker was named one of the top 10 most impressive and influential feats of engineering. Around 200,000 pacemakers are fitted in the U.S. every year, making Greatbatch's invention a crucial part of our modern healthcare system.

Post-it notes

While many of the accidental inventions on this list have changed the direction of medicine or saved millions of lives, there are some that have simply made our lives much easier — the Post-it note being one of them. This is a classic case of an experiment failing miserably, only to uncover something that no one even knew we needed.

In 1968, a chemist named Spencer Silver was trying to develop, essentially, one of the strongest types of glue – one to be used on aircraft. Instead he created a weak one, though it had the unusual property that it stuck well but was easily removed. Unknown to him at the time, Silver has discovered the intriguing properties of microspheres. A few years later, his colleague Art Fry was looking for a bookmark for his hymn book, and he chose to use Silver's glue on paper, knowing it could be removed without leaving behind unsightly residue. Between them, Silver and Fry saw the potential of this little square of sticky paper, and they went on to develop the Post-it note together. The bright yellow color of the Post-it was also a happy accident — when trialing their product in the early stages, yellow was the only color of paper they could find. Without Silver's determination to find a use for his failed adhesive, our office supplies would have never known the colorful joy of a block of Post-it notes.

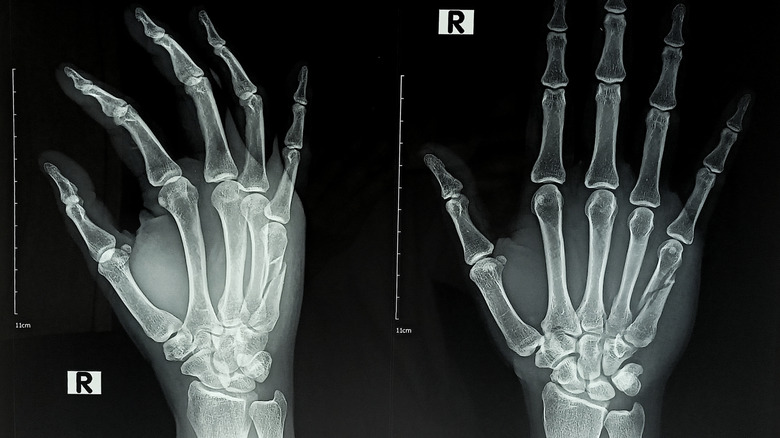

X-Rays

When German physicist Wilhelm Röentgen was conducting an experiment with cathode ray tubes in 1895, he noticed something intriguing. Having covered the tubes completely to block light, rays had somehow managed to escape and produce a glow. Whatever was producing the light was able to travel through solid objects, as he would soon find out when experimenting with a variety of materials. He took an image of his wife's hand to show that the mysterious rays could pass through human flesh, but not bone, allowing bones to be seen for the first time without cutting open the patient.

The "X" in x-ray comes from the fact that Röentgen didn't know what these rays were, so he labeled them "X" for unknown, and the name stuck, though they are officially called Röentgen rays. Once the news of his discovery began to spread, the potential of x-rays quickly became clear. In 1901, he deservedly won the first ever Nobel prize in physics for his discovery, which soon transformed the medical field. Modern x-rays use specific elements and can detect pneumonia, cancer, and dental issues as well as broken bones, thanks to Röentgen keen observation and problem-solving skills.

Microwave oven

If you've ever stowed a chocolate bar in your pocket, only to realize later that it has melted, you likely didn't share the same reaction as Percy Spencer did in 1945. Spencer was working with magnetrons, a source of microwaves, while in the middle of a radar project. Noticing that his chocolate snack had melted as he worked, Spencer wondered if the microwaves could be responsible for the cooking effect.

To confirm his theory, Spencer used an egg and later some popcorn to see what happened to them in close proximity to the microwaves. When the egg exploded and the kernels popped, it was enough to convince him to patent his discovery and set about creating the microwave oven. The first commercial oven was available a few years later, and it was around the size of a refrigerator. Over the subsequent decades, they became smaller and more affordable, and by the late 1980s, they were beginning to appear in kitchens, revolutionizing home cooking as they did.

The microwave in your kitchen contains a magnetron similar to the one Spencer was working with, which directs microwaves at your food, making the water particles vibrate. This generates friction, which cooks the food quickly and with little fuss. Today, more than 90% of homes in the U.S. have a microwave oven, making Percy Spencer's fortuitous discovery and subsequent invention a crucial time saver in the lives of most people.

Teflon

While some fortuitous inventions over the centuries have happened by pure accident, the majority are due to the determination and perseverance of the scientists who spotted something unusual. Roy J. Plunkett is a perfect example, as an American chemist who felt the need to investigate further when his refrigerant gas he was working with seemed to disappear. After further examination, Plunkett and his colleagues discovered that the tetrafluoroethylene gas he was working with had polymerized, turning into a slippery white solid.

Plunkett ascertained that his new example of a polymer compound had unique qualities that could prove very useful. It was incredibly stable and resistant to heat and virtually all chemicals, and it's still now considered to be one of the most slippery substances that exists. This led to the development by DuPont of non-stick coatings on cookware, and the brand name Teflon is now widely used to describe polytetrafluoroethylene. This non-stick cookware was a revelation for home cooks, allowing for much easier cooking of meals and significantly less clean-up.

PTFE is also used in industries other industries — textiles, aerospace, and electronics have all benefited from the discovery and commercialization of this wonder substance. So, next time you manage to clean up your frying pan in a matter of seconds, take a moment to thank the tenacity of Roy J. Plunkett and his desire to find out where his gas had disappeared to.

Viagra

Now the most famous little blue pill in the world, Viagra was never meant to be used to help things along in the bedroom. In the early 1990s, scientists at Pfizer were working on creating a new angina medication, sildenafil citrate. Since angina restricts the blood vessels to the heart, the purpose of the medication was to open them up and relieve pain and discomfort in the chest. Trials of the drug showed that it was unsuccessful, and it was nearly discontinued, until the nurses tending to the patients noticed a strange side effect — it was causing long-lasting erections in males.

It turned out the drug was doing exactly what it was meant to by dilating blood vessels; it was just doing it on the wrong organ. Once this became apparent, Pfizer researchers began to test the drug on impotent men — and realized they had discovered something groundbreaking. Until the development of Viagra, there was no medication that could treat erectile dysfunction, leaving many men frustrated and embarrassed by their condition. By 1998, Viagra was available on prescription as a treatment for erectile dysfunction, and instantly became one of the most successful drugs ever created – by 2012, it was bringing in sales of more than $2 billion per year. With erectile dysfunction affecting increasingly more men each year, including younger men, Viagra remains one of the most significant accidental discoveries of the last century.

Radioactivity

In 1896, Henri Becquerel made a breakthrough in his investigation into fluorescence, and had the sun been shining that day, the significance may have gone unnoticed. In light of the recent discovery of x-rays, Becquerel was intrigued by the concept of fluorescence and phosphorescence. He has been studying how uranium behaved after being exposed to the sun, and he found that it emitted rays that could be seen on photographic film, in a similar way to x-rays.

In February 1896, he was continuing with his experiments, and he was frustrated by the presence of clouds in the sky — without sunlight, he couldn't find a use for his uranium crystals, as they would not be able to absorb the light they needed to fluoresce. He tucked the uranium away in his drawer and left them there with the photographic film. To his surprise, when he returned to them a few days later, there was an incredibly clear image of the crystals on the film, despite the lack of sunlight. Becquerel correctly deduced that the uranium was emitting rays without being exposed to the sun, and thus the concept of radioactivity was born.

Becquerel's discovery led to Pierre and Marie Curie investigating the phenomenon further, and shortly after, polonium, thorium, and radium had all been discovered. It instigated a new branch of physics and chemistry that would lead to the development of new medicinal techniques, including treatment for cancer.

Super glue

Super glue is a feature of most toolboxes around the country, and our DIY lives have been transformed by its unique ability to bond objects together so securely. Its proper name is cyanoacrylate, and it was first created in 1942 by Dr. Harry Coover. Coover was attempting to make sights for the guns of Allied soldiers, and one of the polymers he came across was cyanoacrylate. Its ability to stick to everything it touched was of no use to Coover at the time, as it wasn't suitable for his current project, so he dismissed it.

Nine years later, Coover was on a mission to form another polymer, this time for jet canopies. He returned to the cyanoacrylate from a decade earlier, and this time, he saw the potential it had. Within a few years, superglue had been patented and became an instant success. Its ability to bond to virtually any surface — metal, plastic, and, as many of us have found out the hard way, skin — made it incredibly useful for both household and industrial projects. It requires no heat or pressure to work, with just a drop of moisture causing it to set firmly.

Super glue was used in the Vietnam war as a surgical aid to close up wounds until patients could get robust medical treatment, which led to many lives being saved, something Coover was understandably very proud of. What started as a failed project has become a household essential and a multi-million dollar market.

Plastic-eating bacteria

Plastic has been one of the most transformative inventions of the 20th century, allowing us to replace objects made of wood, paper, and metal with alternative versions that are waterproof, non-rusting, and lightweight. However, in recent decades we have become painfully aware of the one major drawback of these versatile polymers – - their reluctance to naturally degrade.

Kohei Oda and his team were trying to find bacteria that could soften plastic in 2001, and came across something remarkable. They discovered a microorganism that was completely breaking down the plastic and effectively eating it. As groundbreaking as this discovery seems, 20 years ago, the plastic problem was nowhere near as recognized as it is now, so Oda's findings were not met with much enthusiasm. However, in light of our serious plastic pollution issue across the world, this bacterium could prove to be crucial. With the raw materials of plastic bottles taking around 450 years to break down, a drastic solution is needed, and these plastic-munching bacteria may just be the answer.