Almost Famous: How William Weston Became England's Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus is widely known as the first European to set foot in the "new world" in 1492. Although he thought he landed in India, he actually reached the island now split into the Dominican Republic and Haiti and never got close to what is now the United States. Instead, Italian explorer John Cabot is credited as the discoverer of North America in 1497 under the commission of King Henry VII. However, historians following the surge of exploratory expeditions throughout the late 15th century to early 16th century believe that William Weston was on the same voyage and the first Englishman to set eyes on the northern continent.

Weston's place in the history books has been overlooked mainly because he and other first-hand observers didn't leave detailed accounts. Historians have scoured diplomatic letters, charter details, and receipts to piece together the little information they have, explains Evan T. Jones, senior lecturer in Economic and Social History at the University of Bristol and co-author of "William Weston: early voyager to the New World" published in the Historical Research journal in 2018.

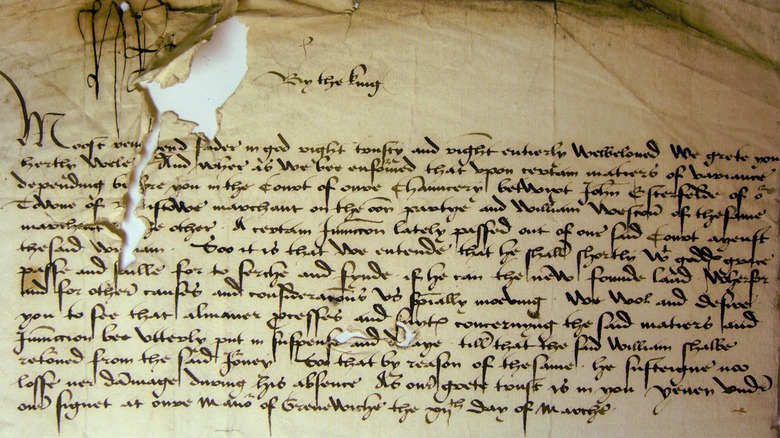

As part of The Cabot Project, Jones has continued to follow the findings of Dr. Alwyn Ruddock, a now deceased member of the Institute of Historical Research who uncovered evidence in the 1960s and 1970s that Bristol men had reached North America before Cabot. Combining their research, it's believed that Weston (a minor Bristol merchant) was the first Englishman to lead a North America-bound voyage. The key evidence is a letter from King Henry VII, which was published in Historical Research in 2010, in addition to evidence that he sailed under Cabot's patent — a permit to undertake cross-Atlantic voyages in search of new lands, which can be assigned to third parties and was awarded in 1496.

What historians know about William Weston

Historian Evan Jones and fellow researcher Margaret Condon, co-author of "William Weston: early voyager to the New World," still aren't certain about Weston's familial connections, but they've been able to trace his activities as a merchant via the Bristol port's customs accounts dating from the late 1460s to the late 1480s. More specifically, he appears in the accounts fairly regularly starting in 1469. For about 20 years, he traded on a level similar to that of an established Bristol merchant's or shipowner's servant or agent and almost solely with Portugal.

Meanwhile, Bristol men were also taking exploratory voyages from the port, and there was talk of the Island of Brasil, which they believed was home to the valuable dye-wood of the same name. In 1480 and 1481, local merchants tried to find it again, and it was so legendary that they believed Cabot's 1497 discovery was the famed island. So, it seems coincidental that Weston's name doesn't appear in the customs accounts quite as much after 1480, although he was still recorded shipping goods on the Anthony until it was shipwrecked in 1488.

After the shipwreck, Weston seemingly ceased his overseas trade activities and eventually married sometime between 1491 and '92. Not much is known about his life before Cabot's arrival in 1495 to '96, but court accounts show that he faced financial ruin. Even though it's not clear why, it's believed that Cabot brought Weston onto his crew, feeling a kinship with him because of their similar life woes. Historians surmise that the pair regarded the 1497 expedition as a gamble, and they were rewarded by King Henry VII for their success. However, Weston's contribution to English exploration of the New World was forgotten soon after with his death a few years later.