The 5 Worst Things To Ever Happen On The ISS

In November 2024, the International Space Station (ISS) faced an unexpected challenge when the Russian Progress 90 spacecraft — an unpiloted resupply ship launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan — docked at the station's Poisk module. Upon opening the hatch, astronauts onboard detected an odd odor and observed unidentified droplets, causing them to close it immediately.

Soon after, air scrubbers (a kind of air purifier that uses filtration, cooling, or moisture as air flows through the device) were employed while contaminant sensors kept an eye on the air quality inside the station. The following Sunday, it was determined that the air quality inside the ISS was at normal levels and posed no risk to the crew onboard. "There are no concerns for the crew," NASA said in an official statement on the event, also explaining that "the crew is working to open the hatch between Poisk and Progress while all other space station operations are proceeding as planned."

The incident was far from the first unsettling mishap that the ISS and its crew have endured over the years and underscores the unpredictable and tenuous nature of space missions. Despite rigorous protocols and safety measures, things can and do go wrong. Astronauts need to be prepared to address unforeseen challenges that arise in the wholly unique environment of space, which explains why there is a list of foods that astronauts are banned from eating on the ISS. But while space exploration is fraught with potential hazards, not all incidents are perilous. Here, we take a look at five of the worst things to ever happen on the ISS and what they taught the professionals about life in space.

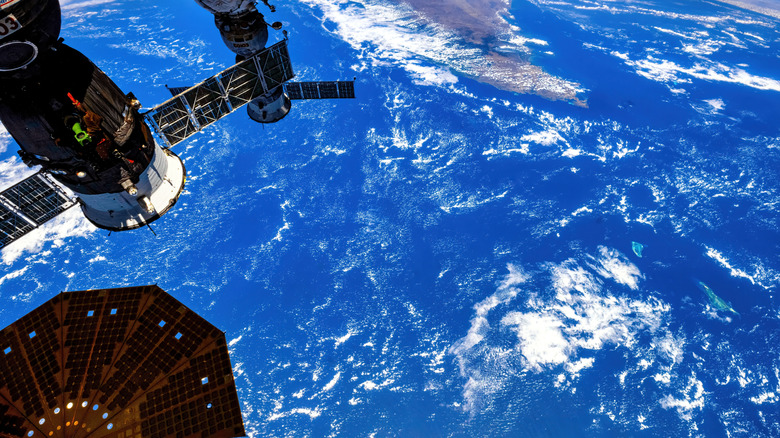

ISS air leaks

Since September 2019, the ISS has grappled with a persistent air leak problem in the Russian Zvezda service module. Initially minor, the leak has progressively worsened, with air loss reaching 3.7 pounds per day by April 2024. Despite extensive investigations, the exact cause remains elusive, though both internal and external welds are one of the suspected contributors.

NASA was initially tight-lipped about the issue until its Office of Inspector General released a September 2024 report, entitled NASA's Management of Risks to Sustaining ISS Operations through 2030. In the report, NASA noted that it had been unable to reach an agreement "on the point at which the leak rate is untenable" with Roscosmos, the Russian government organization that operates its space program. While NASA officials remain concerned that a catastrophic failure at the station is possible, there appears to be no agreement between it and Roscosmos on the exact severity of the issue. For now, a hatch between the U.S. and Russian sections is being kept closed, an uncomfortable but attainable compromise while Roscosmos continues to investigate the leaks.

These disagreements extend to more than just the source of the leaks, however. The ISS's planned deorbiting — in which the aging station will be intentionally burned up in the atmosphere in 2030 — requires Russian propulsion capabilities to do so. However, the report added that Roscosmos had, as of yet, failed to commit to the agency's plan.

A near drowning in space

On July 16, 2013, during Expedition 36, European Space Agency astronaut Luca Parmitano embarked on what was planned to be a routine spacewalk outside the International Space Station. Early in the extravehicular activity (EVA), Parmitano reported a sensation of water at the back of his head inside his helmet. Initially small, the amount of water quickly increased, covering parts of his eyes, nose, and ears, impairing his vision and hearing, and affecting his ability to breathe.

Recognizing the severity of the situation, mission controllers made the critical decision to abort the planned 6.5-hour spacewalk just 92 minutes in. Parmitano, accompanied by NASA astronaut Chris Cassidy, carefully navigated back to the airlock, where inspection of Parmitano's suit revealed roughly 1.5 liters of water had leaked into his helmet — enough to potentially asphyxiate him.

An investigation into the incident revealed that the water intrusion was caused by a blockage of inorganic materials in the drum holes of the water separator of Parmitano's Extravehicular Mobility Unit, the space suit that astronauts wear during walks on the ISS. The blockage caused water to backflow into the ventilation system and, subsequently, into Parmitano's helmet. Interestingly, during a prior spacewalk a week earlier, Parmitano had similarly reported a small amount of water in his helmet, but it was mislabeled as a leak in his drink bag.

When the ISS almost fell out of orbit

In June 2007, during the STS-117 mission, the International Space Station faced a critical challenge when Russian computers responsible for propulsive altitude control and command functions experienced multiple failures. These malfunctions, which manifested as a series of automatic and manual restarts, meant the station lost power over its automatic thruster controls, jeopardizing the station's ability to maintain its orientation and, more crucially, its stability in orbit.

As a temporary fix, the station's altitude control was taken over by the shuttle Atlantis, which was docked at the ISS. The key issue was that if the shuttle left, the station itself wouldn't be able to regain altitude control when the shuttle undocked. While the shuttle kept things steady, Russian and U.S. teams worked to bring power back to the failed computers, which they were able to do by bypassing the secondary power circuitry to deliver an uninterrupted "ON" command.

Later investigations revealed that the point of failure was cable corrosion in the unit of the computer that monitors power, which led to an electrical short. The corrosion was likely caused by the cables' proximity to an air separator, which raised the humidity levels enough to lead to the cables' degradation. This incident highlights how a seemingly minor technical flaw could have led to a catastrophic failure of the entire station.

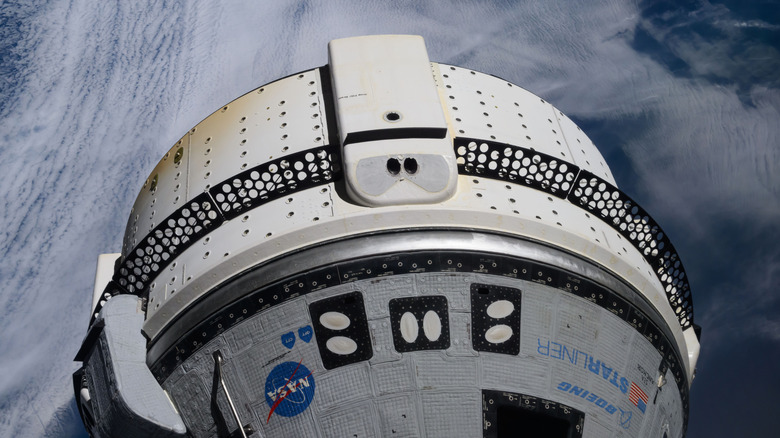

Boeing's troubled Starliner docking at ISS

Boeing's Starliner spacecraft was meant to be a key player in NASA's Commercial Crew Program, an endeavor aimed at ferrying people to and from the International Space Station via partnerships in private industry. However, its long-delayed first crewed mission in June 2024 ran into major complications. Astronauts Butch Wilmore and Sunita Williams — who comprised Starliner's test flight crew — launched aboard the spacecraft, which experienced problems docking with the ISS after five of its 28 thrusters malfunctioned and several helium leaks were detected.

The two were expected to return just a few days later, but after the issues involved with the launch, NASA decided the risk was too high for Williams and Wilmore to return on the Starliner spacecraft. The pair will instead return sometime in early 2025 on a SpaceX Dragon. This left Starliner to attempt a crewless return journey to Earth, and when it undocked from the ISS in September 2024, yet another of the craft's thrusters failed, and a navigation system glitch occurred after coming out of a reentry communications blackout. Thanks to built-in system redundancies, the incidents did not compromise safety, and Starliner successfully landed at White Sands Space Harbor, New Mexico on September 7, 2024.

The mission has put Boeing's ability to live up to the high safety standards that space exploration demands in serious doubt. Starliner's failure has not only delayed future crewed missions but also cost the company billions of dollars. The company is now under pressure to fix Starliner's issues or risk being sidelined as NASA increasingly relies on SpaceX's Crew Dragon for ISS operations. In any case, the event underscores the importance of safety when dealing with getting people to and from the ISS.

A 2 millimeter hole, a big problem

In August 2018, the International Space Station experienced a minor drop in cabin pressure, prompting crew members to investigate. They discovered a 2-millimeter hole in the orbital module of the Soyuz MS-09 spacecraft, which was attached to a Russian segment of the station known as the Rassvet module. Initially applying Kapton tape — a carbon-infused polyamide tape — to seal the leak temporarily, astronauts fixed the hole using an epoxy-based sealant. The measures were successful in stabilizing the station's internal pressure.

On December 11, 2018, Russian cosmonauts Oleg Kononenko and Sergey Prokopyev conducted a seven-hour spacewalk to inspect the hull of the Soyuz MS-09. The two captured images and collected samples from the area around the hole to gather information on the cause of the breach. The origin of the hole led to various speculations. Initial concerns considered the possibility of a micrometeor impact. However, the hole appeared to have been human-made, like the result of drilling. And while some have speculated that the hole was a potential case of intentional sabotage, ISS crew members and other officials have dismissed the idea, pointing to a far more probable mistake in the craft's construction on Earth.

This unsettling incident underscores how even the smallest oversight can become a significant safety risk in space. If you're interested in learning more about things going on in low-Earth orbit, check out our guides to the temperatures of space around the Earth and the reason why stem cells grown in space have doctors so excited.