The Tragic Story Of The Scientist Destroyed By Her Own Discoveries

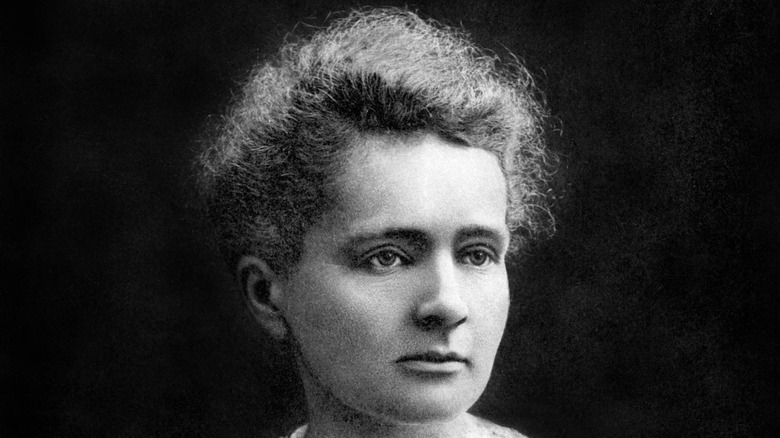

Marie Curie is a name that is now known worldwide thanks to her association with cancer care, but few people know the compelling, tragic story of her scientific journey. From humble beginnings in Poland to her groundbreaking discovery in Paris that would change the face of science, Curie was a remarkable woman who did not let adversity beat her down.

In a male-dominated industry she was determined to prove herself, and won not one, but two Nobel prizes. She was the first person to ever do so, proving that she was capable not only of matching her male peers, but of surpassing them!

Curie's triumph came with a tragic twist, as the very elements that brought her success would ultimately be her downfall. Her lack of understanding of the unique properties of radium meant that she was slowly being poisoned by her own discovery. Radiation would eventually be used to save millions of lives as a cancer treatment, but Curie would not live to see it reach its potential, as the effects from the radioactive elements led to her untimely death at 66. Let's uncover the sad truth behind Marie Curie's amazing discovery, examining the highs and lows of her impressive science career.

Early life and fascination with science

Marya Skłodowska was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1867, as the youngest in a family of five children. Her mother and father were both teachers and Marie was a keen reader and avid learner. Tragedy struck the family in Marie's formative years, losing both her eldest sister and mother to illness. Despites these losses and the family's difficult financial position, Marie flourished in school, graduating at the top of her class and being awarded a gold medal at graduation.

Along with her siblings, she developed a love of academia and science from her father, and would have loved to follow her brother Joseph to medical school in Warsaw. Higher education, let alone science, however, was not a path that women were allowed to take in Poland at that time. Instead, with her sister Bronya, her further education would take place at a secret school known as the Floating University.

As much as this education opportunity was inspiring, Marie and Bronya knew that they needed to attend one of the prestigious European universities that would allow women to attend. They came up with a plan — Marie would get a job to support Bronya's education in Paris, and once she was qualified, Bronya would then repay the favor. Marie got a well-paid job as a governess and continued to teach herself physics and chemistry. After many years of hard work, and with the help of her father's new job, there was enough money for her to make the trip to Paris herself.

Paris and meeting Pierre

Marie Curie arrived at the prestigious Sorbonne university in 1891, and she could never have known the path her life was to take in the coming years. She lived alone in Paris' Latin quarter, and she was so engrossed in her studies that she was known to faint from hunger after forgetting to eat.

Determined to make up for the gap in her official education, she completed two masters degrees by the end of 1894 — one in physics and the other in math. She caught the attention of senior scientists, and was offered a scholarship which led to her meeting her future husband.

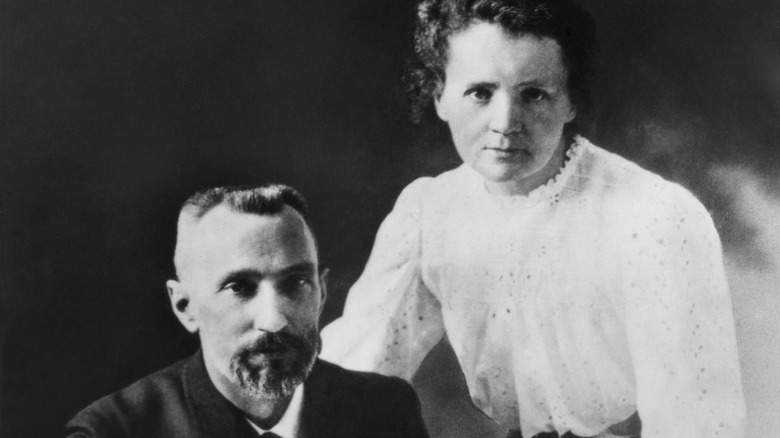

Pierre Curie had been studying magnetism, and connected deeply with this woman who shared his passion for science. After they both completed their doctorates, they married in 1895 and cemented the partnership that would lead to one of the most significant discoveries of the 20th century.

Her groundbreaking experiments

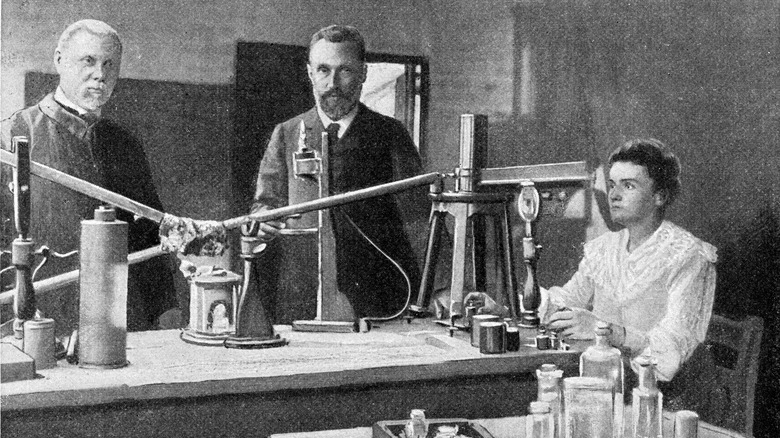

After the birth of their daughter Irene in 1897, Marie Curie set about finding a subject to study for her doctorate. Although Henri Bequerel's (somewhat accidental) scientific discovery of radiation had created little excitement in the scientific community, Marie was intrigued by these new rays, and chose to continue to explore them.

Using an electrometer that Pierre and his brother Jacques had invented, she discovered very quickly that thorium produced the same mysterious rays as Becquerel's uranium had. Upon further investigation, Marie discovered something that at the time was astonishing: It didn't matter what compound uranium or thorium were a part of, they still produced the same radiation. The amount of radiation was only proportional to the quantity of uranium or thorium in the sample.

This blew open the widely held belief that atoms were unchangeable, as the Curies would soon work out that the radiation was coming from the nucleus of the atom, rather than the outside. This revelation set the groundwork for understanding how the nucleus of an atom affects its properties, which would eventually lead to the field of nuclear physics. Inspired by her discovery, Marie set about testing the entire known periodic table, finding that there were no other elements that produced this effect. Once she moved on to testing uranium and thorium ores, however, she was presented with astonishing results.

Discovery of polonium and radium

On testing the ore known as pitchblende, Marie Curie discovered that it produced more than four times the radioactivity that was expected from the uranium it contained. She correctly deduced that this must be due to another radioactive element contained within. In the coming months, the Curies successfully isolated not one new element, but two. Polonium was named after Marie's homeland, and radium was suggested for the second. They also came up with the term radioactivity, which was used for the first time in their 1898 paper.

The next few years would mean extraordinary work and effort from both Curies, as they attempted to isolate the two proposed new elements and calculate their atomic masses. They worked in a shed near Pierre's school, and surrounded themselves with kilograms of the radioactive pitchblende at a time. Finally, in 1903, she presented her results in her thesis. According to The Nobel Prize official site, the committee she presented to, of whom two would become Nobel laureates themselves in future years, cited Marie's work as "the greatest scientific contribution ever made in a doctoral thesis."

Intrigued by the mysterious glow emanating from the radium compounds, Pierre and Marie frequently carried them about on their person, unaware of the devastating effect it would have. As much as their amazing discovery would change the face of science, it would also sadly become Marie's downfall.

The first ever female Nobel laureate

At a time where women were not considered even close to being equal to men in science, Marie Curie was determined to prove that notion false. When she published her thesis in 1903, she became the first woman in France to earn a doctorate. Although plenty of distinguished scientists were beginning to take note of her extraordinary work, including Ernest Rutherford and Lord Kelvin, the French Academy of Sciences did not acknowledge her contribution, nominating only Pierre alongside Henri Becquerel.

Thankfully, Magnus Goesta Mittag-Leffler, a Swedish Mathematician, was able to influence the decision after Pierre insisted that his wife should be recognized for her work, and Marie was rightly honored alongside the two men. The Curies' work built upon Becquerel's discovery of uranium years from a few years earlier: The three scientists between them had advanced the world of physics' knowledge of radioactivity, which would lead to unprecedented progress in medicine in the coming century.

The tragic death of Pierre

The Curies seemed unstoppable, but tragedy was just around the corner. In 1906, when crossing the streets of Paris in the rain, Pierre slipped on the cobbles and was hit by a horse-drawn carriage that killed him instantly. At the age of 38, Marie was now a widow with two young children, left to continue their pioneering work alone, in an industry that was reluctant to recognize her.

Shortly after his death, Marie was offered Pierre's teaching post at the University of Sorbonne, and became the first ever woman to hold such a position at the institution. She was determined to honor her husband's memory, and set about working towards the Radium Institute, which would eventually open in 1915. Claims from fellow scientists that radium was not actually an element spurred her on to prove once and for all that the theories she and Pierre had hypothesized were correct. Her relentless work led to a recognition that no other scientist had achieved — a second Nobel prize.

A second Nobel prize despite personal controversy

Marie Curie had originally set out to prove that there were female scientists who could change the world and achieve everything that a man could in science, but she ended up going one step further. No man had ever been awarded two Nobel prizes, and Curie achieved that astonishing second award in 1911 for the isolation of elemental radium. Even more impressively, she remains to this day the only person to receive a Nobel prize in two different scientific fields, since her second was awarded in chemistry.

Her personal achievements were somewhat overshadowed though, by the negative press attention she received over her affair with a married man. Her relationship with physicist Paul Langevin was twisted by the press and painted the foreign Curie as a villain. For this reason, she was advised by the committee to decline the prize. According to Native Scientists, she replied, "The prize has been awarded for the discovery of radium and polonium. I believe there is no connection between my scientific work and the facts of my private life." Curie was determined to let her extraordinary work rise above the personal scandal, and deservedly collected the award she had earned.

The radiation begins to take its toll, and her untimely death

Despite signs of ill health in Pierre Curie before his death, Marie Curie was unaware of the severity of the dangers posed by radioactive substances, including the radium she is so famously associated with. While nowadays, handling radium would require lead-lined gloves and clothing, Marie carried a test tube of the substance around in her pocket and kept some in her nightstand, enjoying the glow it produced.

Her health declined in 1934, and doctors were initially unable to find a cause. Eventually, they concluded she had aplastic pernicious anemia, a blood condition likely caused by the long-term proximity to radiation. She died in July 1934 at the age of 66, and had to be buried in a coffin lined with lead since her body was highly radioactive.

Marie Curie was initially buried next to Pierre in Sceaux Cemetery, Paris, but they were both moved to the Pantheon in Paris in 1995. This famous French institution honors the greatest contributors to French society, and the Curies now share a resting place with Voltaire and Victor Hugo, among many others. In true Marie fashion, she was the first woman to be buried at the Pantheon as a result of her achievements. Even in death, she continued to be a trailblazer, and now has the recognition she so desperately craved in her early career.

How Marie Curie's discoveries changed the world

Marie Curie is famous the world over for her association with cancer treatments, but not all of the uses for radium were quite as successful. Though she wasn't directly involved, an entire industry was developed using the glowing qualities of radium, with scientists quite unaware of the extreme dangers of the element. In fact, it was assumed that the energy given out would in turn improve energy levels in those who were exposed to it.

The tragic story of the Radium Girls in three factories across the midwest and northeastern U.S. is one of the most famous and shocking examples of the misunderstood radiation. While painting watch faces during the war to cause them to glow in the dark, the girls were encouraged to bring the radium-covered paintbrushes to a point with their lips, meaning they were ingesting the dangerous element on a daily basis.

Fortunately, the Curies had other plans for radium, having noted early on how it burned tissue, and theorizing that it could potentially kill cancer cells. At the turn of the century, Pierre had experimented on himself by strapping radium salts to his arm for 10 hours, then observing how the wound healed. Marie continued to investigate medical uses for radium after his death, and became director of the French Red Cross Radiology Service during the First World War, developing mobile x-ray units to help locate shrapnel embedded in soldiers' bodies. In contrast to the devastating consequences of the commercial radium industry, Marie Curie's efforts during the war are thought to have saved over 1 million lives.

Her legacy

There can be no doubt that the work of Marie Curie, and particularly the discovery of radium, changed the world of science and medicine as we know it. Her "pure science" work, as she described it (via AIP), investigating the properties of this mystery substance without knowing its purpose, eventually led to significant advances in cancer treatments. The Marie Curie Hospital in London opened a few years before her death, and after being destroyed during the war, the Marie Curie cancer charity was set up in her name.

After Marie's death, her daughter Irene continued her parents' vital work researching radioactivity, and in 1935 won the Nobel Prize jointly with her husband for creating artificial radioactive elements. With expensive radioactive elements now being replaced with artificial alternatives, radiotherapy as a cancer treatment was able to advance much more quickly and at a significantly reduced cost. In the ultimate scientific tribute, in 1944 the new element curium was named to honor the exceptional work of Marie and Pierre. It was one of the first elements to be named after a scientist, though many more would follow.

The Marie Curie Foundation (via Radiotherapy UK) estimates that more than 1 million lives could be saved every year by 2035 if radiotherapy were available to all who need it. Even a century after her death, her contribution to medicine is still being felt. We have no way of knowing when radioactivity would have been brought into the limelight without the tireless work of Marie Curie, but it is clear that her groundbreaking research paved the way for modern medicine to save countless lives.