The Reason Dodo Birds Went Extinct Is More Depressing Than You Thought

The dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) is one of history's most famous cautionary tales: a flightless bird that vanished forever because of human recklessness. For centuries, the standard narrative has been relatively simple: Portuguese and Dutch sailors arrived on the island of Mauritius in the 1600s, found a slow, defenseless bird that didn't fear humans, and hunted it into oblivion. But recent research suggests the truth is far more complex and depressing.

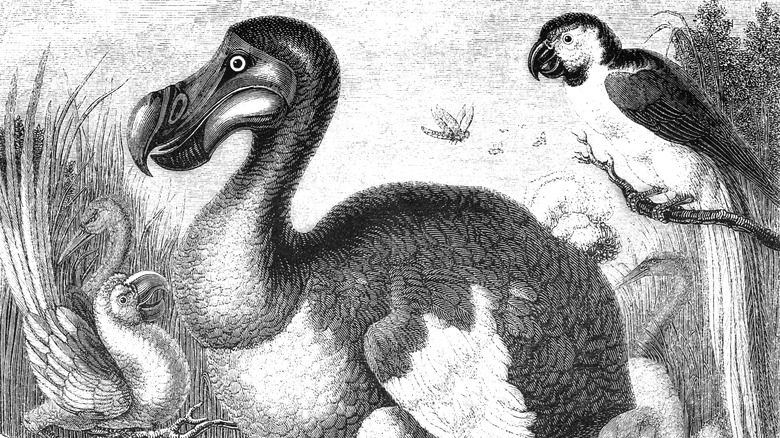

For starters, the dodo wasn't the bumbling, clumsy creature it's often portrayed to be. It was actually a well-adapted forest bird with strong legs and a keen sense of its environment. The dodo was related to pigeons, and having spread over the ocean to Mauritius, where it faced no predators, it likely grew larger and eventually became flightless. Because of that lack of natural predators, the bird lacked a natural fear response to the European settlers that visited and began making permanent encampments on the island. Those settlers brought with them a host of animals and plant seedlings that would irrevocably change the environment the bird had so well adapted itself to.

The result? Within a century after its discovery, the dodo had disappeared from the face of the Earth. But because the dodo is one of a few animals in the historic record to have essentially vanished the moment it was discovered, much of the information surrounding its behavior, disappearance, and even the details of its taxonomic classification remains a subject of debate even today. Understanding the real reasons why it went extinct forces us to rethink the way we view human impact on the natural world. If there's one lesson to take from the dodo's fate, it's that human influence on ecosystems is rarely straightforward — and almost never harmless.

Debunking the myth of the dumb dodo

The dodo has long been caricatured as a sluggish, dim-witted bird, emblematic of evolutionary failure. But recent work from scientists like Leon Claessens, a professor of Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, has begun to reshape our understanding of this misunderstood creature. It's likely that the word "dodo" comes from the word "dodaersen," a name seen in early Dutch accounts of the bird that roughly equates to "fat backside." This is because the bird was remarkably large, weighing in at around 40 pounds and standing 3 feet tall.

"You basically just have a large ground-dwelling seed-eating organism that is large [and] rotund, so it can store a lot of food, and that also means that it makes it very, very sturdy and very resilient to climatic fluctuations," Claessens told the American Chemical Society. Another prevailing myth is that the dodo was exceptionally stupid, a misconception that likely stems from its trusting nature around humans. In reality, research indicates that the bird's brain-to-body size ratio was comparable to that of modern pigeons, which are known for their problem-solving skills and trainability. But much of the dodo's biology is shrouded in mystery. What we do know is that they had large olfactory bulbs for birds, meaning their brains prioritized smell compared to how most birds put a premium on sight.

Researchers from the University of Southampton further discredit the bird's unearned reputation, as summarized by one of the scientists, Mark Young, who says, "Was the Dodo really the dumb, slow animal we've been brought up to believe it was? The few written accounts of live Dodos say it was a fast-moving animal that loved the forest."

What really caused the dodo's extinction?

The extinction of the dodo bird is too often oversimplified, with many equating it to overhunting by early settlers. A closer examination reveals a more interesting and disturbing portrait, however, one involving an intricate web of factors. When Dutch settlers arrived on Mauritius in the 17th century, they initiated deforestation efforts to establish settlements and agricultural plantations. The pressure of habitat loss became one of several nails in the dodo's coffin, leaving them increasingly less space in which to live and reproduce.

But these early settlers didn't come alone; they brought seedlings for crops they wanted to grow and animals, too. The earliest reports of the island mention goats, chickens, pigs, and even macaques. Suddenly, these animals had found a new food source that lived and nested on the ground, making them and their eggs easy pickings, and accelerating their decline as a species.

Compounding these problems was the dodo's reproductive strategy. Unlike other bird species, it is believed to have only laid one egg at a time. A limited reproductive rate meant that any loss to these new animal predators would have had a significant impact on population recovery. And, while human hunting did contribute to their decline, the combination of habitat loss, the introduction of invasive animal predators (read about the invasive species that California is battling for a modern case study), and the dodo's low reproductive output ultimately sealed its fate. Less than a century after it was discovered — sometime in the 1680s or 1690s — the dodo had disappeared.

Could we revive the dodo?

Advancements in genetic engineering and a deeper understanding of the dodo's ecological role have sparked discussions about the potential for de-extinction and ecosystem restoration. In 2022, a team led by Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary paleobiologist at the University of California Santa Cruz, announced that it had successfully sequenced the dodo's genome using DNA extracted from well-preserved museum specimens. This has laid the groundwork for de-extinction efforts.

Building on this foundation, the biotech company Colossal Biosciences announced in early 2023 its intention to pursue the bird's resurrection, with the ultimate goal of reintroducing it into its native habitat on Mauritius. Shapiro has joined Colossal as its chief science officer, but emphasizes that these kinds of envelope-pushing technological advancements are not a get-out-of-jail-free card. De-extinction efforts like this are "not a solution to the extinction crisis," Shapiro emphasized in an interview with Scientific American. "Extinction is forever."

Beyond this, even if scientists are able to use the genome to bring the bird back, it wouldn't be the dodo that once existed. They would need to edit what are called primordial germ cells in pigeon eggs with the dodo's genome, creating what is essentially a brand-new animal with the genetic instructions of a dodo. Whether or not that is the "same species" is a debate that continues to rage in scientific communities. Complicating matters further is the issue of whether or not we should be spending the resources being put into the de-extinction of existing endangered species.

What the dodo taught us about conservation

The dodo's extinction serves as a stark reminder of the unintended consequences human actions can have on the environment. More than a historical curiosity, its disappearance helped shape the field of modern conservation by demonstrating how habitat destruction, invasive species, and overexploitation can rapidly drive species to extinction. Today, these same threats endanger countless other animals — just check out our list of 12 animals on the brink of extinction for a sober and necessary reminder of that fact. The lessons learned from the dodo's fate continue to influence global conservation strategies.

One of the most important takeaways is the role invasive species play in ecological collapse, a problem not at all unique to the dodo. The Stephen Island Wren and the Guam Kingfisher are perfect examples of this, both of which suffered massive species member loss at the hands of invasive predators. And coming to a better understanding of the dodo's role in its ecosystem also appears to be crucial for informed conservation efforts.

"Dodos held an integral place in their ecosystems," Dr. Neil Gostling, an evolutionary-developmental biologist, told the University of Southampton regarding recent efforts to better understand its biology and ecological role on the island of Mauritius. "If we understand them, we might be able to support ecosystem recovery in Mauritius, perhaps starting to undo the damage that began with the arrival of humans nearly half a millennium ago." While de-extinction remains controversial, there is a consensus that the real priority should be preventing extinctions before they happen. Thankfully, there are plenty of efforts underway around the globe to help the species that need it, leading to things like the comeback story of one of North America's most endangered mammals.