5 Organisms That Are Insanely Hard To Kill

Humans may be the dominant species on Earth, but the planet is also teeming with species whose strength and resilience make us look pathetically weak. The longest-lived animals on Earth can live beyond 10,000 years, and one species, the immortal jellyfish, appears to be capable of infinite regeneration. However, these incredible lifespans are all for naught if the animal is killed by a predator or some other environmental hazard. Resistance to attacks is a whole other story, and some organisms have managed to become nearly impossible to kill.

From animals that live in the most hostile environments on Earth, where no human could hope to survive, to plants that gardeners try desperately to eradicate without success, the natural world boasts survivalists of many kinds. These species offer scientists a unique lens into survival techniques that could potentially help humans venture into new extremes. Now, it's time to meet five of these resilient warriors that, try as their enemies might, refuse to bow out.

Giant African land snails

The giant African land snail has gained a reputation as one of the most destructive invasive species around the world. It originated in East Africa, but has since spread to other continents through the pet trade and as accidental cargo in international shipments. The species is aptly named for its size, reaching up to 8 inches in length, with shells the size of a human fist.

Giant African land snails are voracious eaters, known to feed on more than 500 different plant varieties. Their propensity to decimate local plant populations makes them a major threat to the environment and the ultimate nightmare for gardeners. They can also carry pathogens that threaten human health, including salmonella and rat lungworm. Due to these threats, the United States government has made it illegal to own, sell, or transport any giant African land snails, but for those members of the species that have already invaded new environments, eradicating them is a nearly impossible task.

These formidable snails can survive in a wide range of climates, and have proven extremely stubborn. The only way to guarantee eradication is to kill each snail one-by-one, which requires substantial effort. Crushing the snail will kill it, but this also triggers it to release hundreds of eggs in the process, vastly increasing the problem. Some farmers have even resorted to using flamethrowers against giant African land snails, an incredibly risky approach in dry environments. The only surefire way to safely kill these creatures is to drown them in bleach for at least 24 hours.

Cockroaches

Cockroaches are infamous for being nearly indestructible. Many works of science fiction have depicted cockroaches as survivors of apocalyptic events, in some cases even taking over the world in our absence. Although these depictions are exaggerated for dramatic effect, they stem from truth, as cockroaches have a number of traits that make them extremely hard to kill. For starters, cockroaches are able to regenerate their limbs with ease, allowing them to recover from serious injuries. They are also highly resilient to pesticides, a trait that appears to be growing stronger as they build up resilience to these chemicals.

Cockroaches are famed for their resilience to the effects of nuclear radiation on the environment, being able to withstand up to 15 times more radiation than we can. However, the idea that they could thrive after a nuclear apocalypse is highly exaggerated, and no living thing can survive the direct blast of a nuclear bomb.

Perhaps the most impressive survival trait of cockroaches is their ability to defend against microbial attack. It's no stretch to say that cockroaches are widely considered gross, thanks in no small part to the fact that they often live in very unsanitary conditions and eat rotting foods. This exposes them to countless pathogens, but their cells respond by secreting powerful antimicrobial peptides that greatly reduce the threat of disease.

Bindweeds

Many gardeners can tell tales of their battles with bindweeds. These perennial vines are members of the morning glory family, producing lovely little pink and white flowers. However, they grow at an alarming rate, with roots and tendrils that twist around neighboring plants to rob them of water, sunlight, and nutrients. They form subterranean mats of roots that can spread out as far as a 25 foot radius around the plant, and reach as deep as 20 feet below the soil surface.

Bindweeds are native to Eurasia, but are now found throughout almost all of North America as well, likely being introduced to the continent in the early 1700s as an accidental inclusion in shipments of seeds. As an invasive species, bindweed has had a devastating impact on native plants, as well as on the agricultural industry. The fast-growing vines can outcompete any other plant, reducing farm yields by as much as 80%.

Bindweeds are incredibly difficult to eradicate. In order to actually kill the plant, the entire root system must be removed from the soil. This requires great care, as any root fragments left in the ground will sprout new bindweeds. The roots are resistant to all but the strongest chemical weedkiller, and the only effective way to kill them organically is to block the entire plant from receiving light for at least a year. Even then, bindweed can still return to wreak havoc; each plant also produces over 500 seeds, which can lie dormant for as long as 60 years before sprouting.

Gram-negative bacteria

Each year, more than a million people die from antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections, largely thanks to something called Gram-negative bacteria. These are named not for the unit of measurement, but rather for the Danish scientist Hans Christian Gram, who developed a test used to determine the structure of bacterial cell walls. Gram-negative bacteria are characterized by having a resilient, double-layered outer membrane, which prevents them from absorbing anything from the outside, including antibiotic medications.

Probably the most famous examples of Gram-negative bacteria are salmonella and E. coli, both common culprits in cases of food poisoning. Another example of Gram-negative bacteria is Yersinia pestis, which causes plague, and has led to several of the worst disease epidemics in human history, most notably the black death in the 14th century. Several other life-threatening diseases, including cholera, typhoid fever, meningitis, pneumonia, and sepsis, can all be caused by Gram-negative bacteria, making these resilient microbes one of the biggest public health threats in the world.

Treating diseases caused by Gram-negative bacteria is immensely challenging because they simply refuse to be killed. Thanks to that near-impenetrable outer membrane, Gram-negative bacteria are resistant to most antibiotics, and swiftly build resistance to new medications. Doctors often treat Gram-negative bacterial infections by combining antibiotics or using older treatments that modern bacteria don't get as much exposure to. However, the medical world still lags far behind this threat; It is common for patients with such infections to end up in intensive care, and mortality rates are frighteningly high.

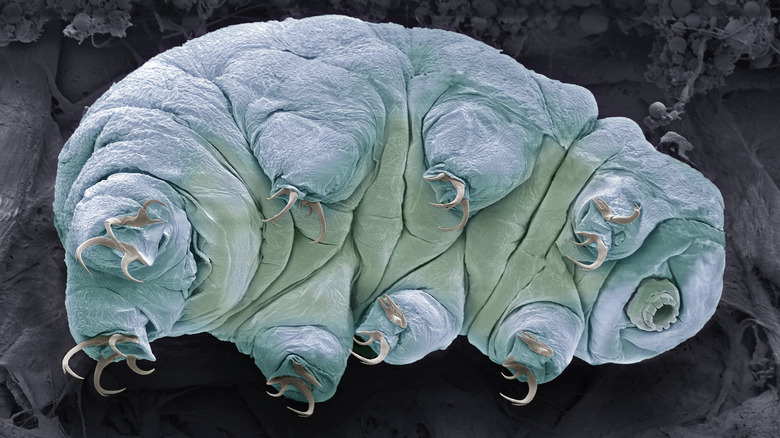

Tardigrades

Tardigrades are the ultimate indestructible organisms, displaying feats of survival that boggle the mind. Also known as water bears due to their snout-like faces, tardigrades are only about half a millimeter long. You can't see them with your naked eye, and yet they are all around you, being one of the only animals that live on every continent, including Antarctica. There are over 1,000 different species of tardigrade, some of which are aquatic and some of which are terrestrial.

Tardigrades have been found on Himalayan peaks nearly 20,000 feet above sea level and in ocean trenches more than 15,000 feet below sea level. They can survive temperatures from boiling to almost absolute zero, and can go as long as 30 years without eating or drinking. Tardigrades are so resilient that scientists decided to send them into the vacuum of space ... and they still survived.

There are two keys to tardigrades' indestructibility. Firstly, their bodies produce a unique protein that shields their DNA from radiation. Secondly, when environmental conditions turn extreme, tardigrades enter a state of cryptobiosis, also known as the tun state. When this happens, the tardigrade forces all of the moisture out of its body and rolls up into a ball. Its metabolism can slow by as much as 99% during this time, and tardigrades can remain in the tun state for decades until conditions improve, when they spring into action once more.