Discoveries That Baffled Archeologists

Researchers across all branches of science have made some amazing discoveries, both on Earth and throughout the universe. However, those discoveries don't always come with a clear explanation. This is often the case with archeology, and numerous ancient finds have stumped scholars.

Studying the material remains of humans from prehistory through to the recent past, archeologists are committed to pursuing an understanding of the human civilizations and cultures that preceded the present day. Some of them even study animal or plant remains to learn more about Earth's natural history, extending into millions of years. To achieve this, they implement a range of technologies — such as carbon or radiometric dating, CT scanners, geographic information systems (like those used in topography), ground-penetrating radar, LIDAR, and optical microscopes.

Even with these technologies at their disposal, some of the artifacts left by our ancestors have continued to baffle archeologists through the present day. Here are just a few of the most mysterious and interesting discoveries.

Shroud of Turin

Discovered in 1354, the Shroud of Turin has been preserved in Turin, Italy, in the Cathedral of San Giovanni Battista since 1578, and is claimed to be the burial garment of Jesus Christ. Measuring 3 feet, 7 inches wide and 14 feet, 3 inches long, the faint images on the linen cloth look as if a man was laid on one half — from feet to head — so that the other half could be doubled over him, also from head to feet. Believers tout it as having been used for Jesus because markings on the cloth are seemingly consistent with his crucifixion wounds. However, it has been the subject of much debate because of doubts about its authenticity.

In the first known historical record, the Shroud of Turin was found in the hands of Geoffroi de Charnay, a famous knight. How it came into his possession, though, is unknown. After its discovery, a local bishop of Troyes condemned it as fake in 1389, and over the ages, scholars have used all manner of scientific methods to determine its authenticity or lack thereof. In 2018, a study published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences demonstrated that the blood stains couldn't have been from Jesus, since the way his blood would have flowed from his injuries doesn't match the markings on the cloth. More recently, researchers published a 2022 study in Heritage that concludes the cloth may be at least 2,000 years old (consistent with Jesus' time), based on the wide-angle, X-ray scattering method of testing.

Unfortunately, the archeological community may never know for sure who the cloth originally belonged to. Meanwhile, the Vatican is careful to refer to the Shroud of Turin as an icon instead of a relic to avoid taking a stance on its authenticity.

Stonehenge

Another long-known archeological find and one of the most famous places in the world, Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, has been an excavation site since at least the 1620s and is one of the oldest mysteries that scientists can't explain. The prehistoric monument was built in multiple stages, starting 5,000 years ago with an early henge. With an inner and outer bank, the circular ditch that encloses an area of about 100 meters in diameter was constructed around 3000 B.C., and is the earliest known major event related to Stonehenge.

Sometime around 2500 B.C., the small bluestones and large sarsen stones were erected in the middle of that circular area. The bluestones came from over 150 miles away, while the sarsens came from 15 miles away. The last known activity at Stonehenge occurred between 1800 and 1500 B.C., although that work appears to be incomplete. The entire timeline means that Neolithic builders were working at the site for about 1,500 years.

Since the Middle Ages, Stonehenge has been the subject of much research and speculation, and what archeologists and historians understand about the monument continues to evolve. King James I was the first to commission the site's excavation in the early 1600s, but it was professor William Gowland who stated for the first time in the early 1900s that the monument was built during the Neolithic period. Studies increasingly suggest that the stones were arranged to be a solar calendar; in 2024 and into 2025, scholars have focused on whether a rare lunar standstill could reveal Stonehenge's secrets.

Remains and tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose II

The discovery of the remains and tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose II, the fourth ruler of ancient Egypt's 18th dynasty, has been puzzling for archeologists for a long time. For some background, Thutmose II had a short reign from 1482 to 1480 B.C. After his death, his royal half-sister wife, Hatshepsut, ruled as queen regent from 1479 to 1458 for her stepson, Pharaoh Thutmose III, who became possibly the greatest military leader of the time.

What's baffling is that Thutmose II's original resting place wasn't in a cache next to the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut (Djeser Djeseru) near the Valley of the Kings — just one of many resting places for the dead in ancient Egypt — where it was found in 1881, alongside the mummified remains of other pharaohs. Instead, it's believed that his original tomb was located 1 to 1.5 miles away in an area now called Wadi Gabbanat El Qurud. It was found in 2022, but not identified until the 2024-25 excavation season, based on shards of alabaster jars inscribed with his name as well as other writing with Hatshepsut's name.

It's believed that Thutmose II was moved from the original tomb about 500 years after his death because it became vulnerable to flooding, being located at the bottom of a slope and under two waterfalls. However, there have always been questions about why Hatshepsut built her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, when her husband was buried elsewhere while she was buried in a Valley of the Kings tomb. With the original tomb seemingly discovered, a new question arises about whether his remains are also still there, in another tomb concealed behind a 75.5-foot mound of limestone and debris.

The Antikythera mechanism

Pulled from a shipwreck near the island of Antikythera in the Mediterranean in 1901, the Antikythera mechanism is one of the most puzzling and stunning discoveries archeologists ever found in Greece. The device was broken into pieces and covered in corrosion, understandably so since it was made of bronze and underwater for such a long time: The shipwreck happened sometime in the 1st century B.C. No other complex mechanism like this — containing materials used for gears and pulleys — is known to have existed in the ancient world, especially in 100 B.C., which is when researchers have dated its manufacture, plus or minus 30 years. In fact, mechanical clocks weren't built until over a thousand years later.

Now known as an ancient computer, archeologists and historians originally didn't know what the Antikythera mechanism was and largely ignored it; X-ray imaging found Greek inscriptions in the 1970s and 1990s, but they were too difficult to decipher. Research on the device didn't ramp up until the fragments were put through CT scans, revealing more hidden writings and inner workings that revealed its purpose as a way to accurately track the movements of celestial objects. Some of these writings were on its case, only parts of which were recovered.

But, while scientists have continued studying the Antikythera mechanism, they still haven't been able to identify exactly how it works because two-thirds of it is missing, and what they do have to work with is in 82 fragments. The closest that they have come is a model made in 2021. Even if they do learn how it functions, questions may still remain about its purpose; was it for teaching, a toy to play with, or something else?

Dead Sea Scrolls

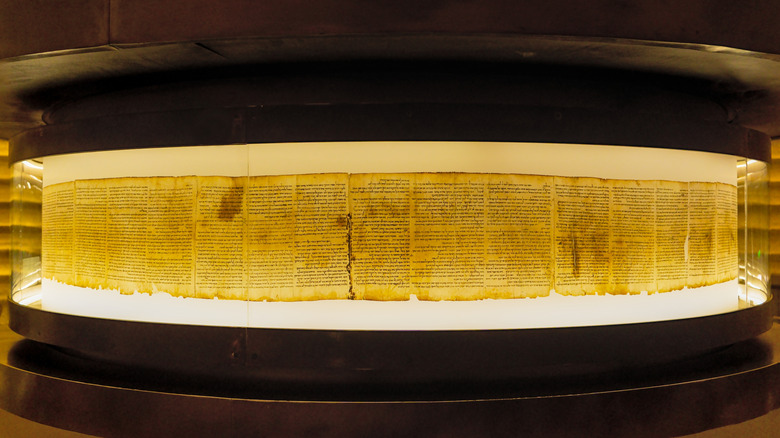

The Dead Sea Scrolls have been studied since their accidental discovery in late 1946 to early 1947 by some teenage shepherds near Qumran, an ancient settlement on the West Bank of the Dead Sea. While supervising goats and sheep, one of them tossed a rock into a cliff-side cave. He wasn't expecting to hear a shatter in return. Upon investigation, they came across a collection of clay jars, seven of which contained leather and papyrus scrolls. Word eventually spread about the discovery, and another 800 to 900 scrolls were found in nearby caves.

Researching the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars have determined that they date from between the 3rd century B.C. and the 2nd century A.D., and believe that the older manuscripts belonged to the Qumran community, which occupied the area from about 100 to 68 B.C. The scrolls contain fragments that represent almost the entire Hebrew Bible, which has allowed scientists to estimate that a stabilized version of the book existed by 70 AD. There are at least excerpts from every book in the Old Testament, while Isaiah is the only complete book to have survived and is dated to have been written in the 1st century B.C.

The mystery behind these scrolls, though, is that no one has been able to pinpoint who wrote them. While most of the texts are written in Hebrew — some in the ancient paleo-Hebrew alphabet — others are written in Aramaic and Greek. On top of that, the Copper Scroll is a standout among the hundreds of leather and papyrus papers because it features Greek and Hebrew letters, and uses unusual spellings and unorthodox vocabulary. These provide a list of silver and gold treasures along with a map of their underground locations, although none of the caches have been found.

Göbekli Tepe

First examined but dismissed in the 1960s, Göbekli Tepe is a megalith far older than even Stonehenge. The main excavation site is on a hilltop about 50 feet above the rest of the landscape — 6 miles from the ancient city of Urfa in southeastern Turkey. It features rectangular pits of pillars and stones standing in circular arrangements. Four more partially excavated circles on the hillside have a similar design: two large, 16-foot T-shaped megaliths in the center with slightly smaller stones surrounding and facing toward them. One of the circles is 65 feet across, and while some of the pillars are blank, others have animal carvings.

Anthropologists from the University of Chicago and Istanbul University initially believed Göbekli Tepe was just a deserted medieval cemetery. When German archeologist Klaus Schmidt read their report in 1994, though, he visited the site himself and began studying it. Geomagnetic and ground-penetrating radar surveys revealed at least 16 additional megalith rings still buried throughout 22 acres of land. On the 1 acre of excavated ruins, archeologists have determined that the giant carved pillars are about 11,000 years old.

Research has continued to reveal more about the property. For instance, the pillars were carved from a nearby limestone plateau, indicating that the area was once inhabited by specialized craftsmen, indicating that other hierarchical forms of human society were emerging at the time. Other researchers have suggested that Göbekli Tepe's pillars and their markings document a devastating comet strike that happened around 10,850 BC, and can be interpreted as a lunisolar calendar, potentially explaining how ancient people used the stars and planets. Plenty of mystery remains, including how it was crafted by people who didn't have metal tools or even pottery.

Bashplemi Lake tablet

A basalt tablet found near Bashplemi Lake in the Dmanisi Municipality of Georgia in 2021 has stumped archeologists; its engraved inscription contains 60 characters from an unknown language, and 39 of them are distinct. The area is known for having an abundance of ancient artifacts. A city gate, residential ruins, and paved streets have been uncovered, and archeologists have found ceramics from the 9th to 11th centuries, coins (mostly Georgian) dating from between the 11th and 13th centuries, silver and gold jewelry, and weapons and tools.

However, Bashplemi Lake has been overlooked as an archeological site since excavations started in the region in 1936. Named by the locals, it's located on a volcanic plateau between the Mashavera river's right tributaries, and the grayish tablet was discovered when the water level was at its lowest. Researchers have compared it to the size of a book, measuring about 9.5 inches long, 7.9 inches wide, and 0.3 to 0.7 inches thick with unprocessed edges and surfaces.

The inscription itself doesn't match with any other known language, but the symbols resemble those found in the Middle East and in areas such as Egypt, India, and West Iberia. Also, it was presumably made with a conic drill and a round-headed tool, indicating high-level craftsmanship. Although the scholars haven't pinpointed when the tablet was etched, they believe it was made during the Late Bronze to Early Iron Age, based on the dating of other artifacts in the region and the shapes of characters in the inscription.