What Life Was Like During Yellowstone's Last Major Eruption

Around 640,000 years ago, a catastrophic volcanic eruption rocked what is now Yellowstone National Park, reshaping the landscape in ways that still define the region today. Known as the Lava Creek eruption, this event was so massive that it ejected nearly 250 cubic miles of volcanic material, hundreds of times that of the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens that covered over 370 square miles of land in ash and dust. When the eruption was over, a vast caldera — a large depression in the ground left by an explosion that collapses the mouth of a volcano — was left in its place, spanning an astonishing 50 by 30 miles.

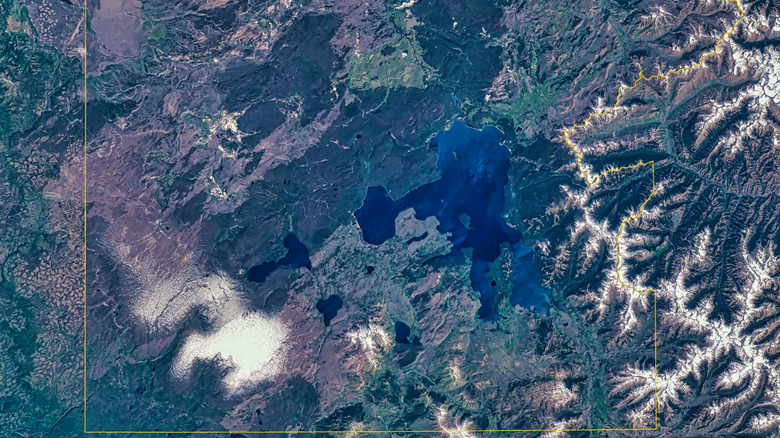

Many know Yellowstone National Park as the beautiful natural paradise that over 4 million people flock to annually to experience, according to the U.S. National Park Service. But Wyoming holds a terrifying secret below Yellowstone — a massive volcanic system whose eruptions have the potential to reshape the climate on a global scale.

These kinds of eruptions don't happen very often. The last major volcanic events before the Lava Creek eruption at Yellowstone, which is one of the top five most dangerous supervolcanoes in the world, happened 1.3 million and 2.1 million years ago. But just because such events don't come around very often doesn't mean they're a complete impossibility. Modern human civilization wasn't even around during the Lava Creek eruption, so it's difficult to conceptualize what such an explosion would have looked like from the perspective of someone living in the area — but it's worth considering. And what science can tell us about the event gives us insight into not only the likelihood of it happening again, but what we would have to do to adapt to just such an eruption today.

The immediate aftermath of the Lava Creek Eruption

So, what happened during the Lava Creek eruption? Well, it's a little more complicated than just a single explosive event taking place. Scientists have recently found evidence for ash flow deposits called ignimbrites that change the timeline and nature of the eruption. Ignimbrite samples taken at Sour Creek dome, located in eastern Yellowstone, indicate that up to four minor eruptions took place before the big one. However, this could also be evidence of the presence of multiple vents that also produced volcanic material during the eruption, so scientists are still debating what happened exactly.

Whatever the case, when the main Lava Creek eruption tore through Yellowstone 640,000 years ago, the region became unrecognizable within a matter of hours. Rivers of molten rock scorched the landscape while massive pyroclastic flows — deadly clouds of superheated gas, ash, and debris — raced across the terrain at up to 100 miles per hour. These flows left substantial volcanic deposits, which are now called the Lava Creek Tuff, which today forms the north wall of the eruption's caldera. While it's difficult to say what radius of land would have been directly impacted, given the size of the caldera the eruption formed, anything within 50 to 100 miles would have likely been devastated, and plant and animal life would have been virtually wiped out due to the extreme heat and suffocating ash.

Registering at an 8 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (the highest number on the scale there is), the column of material ejected from Yellowstone would have reached at least 16 miles into the sky, with atmospheric winds carrying the debris over a significant portion of the North American continent — deposits from the eruption have been found in places as far away as Louisiana.

Lava Creek's effects on the global climate

The Lava Creek eruption would have reshaped the surrounding ecosystems in an instant. In the immediate blast zone, the landscape would have been left a barren, smoldering remnant of forests, boiled streams, and hardened lava. Despite the seemingly irrevocable destruction, areas on land covered by lava flows can bounce back relatively quickly, thanks to a process called primary succession. Primary succession is when plants and animals retake an area sterilized by lava or glacial flows. Given sufficiently wet conditions, forests can even develop in these areas within as little as 150 years, an instant in geological time.

The broader impact that such a supervolcano eruption is going to have is on the climate. However, it's almost impossible for scientists to estimate just how much the global climate would be affected in the event of a Lava Creek–like eruption. Despite this, researchers can look to eruptions in recent history for clues. When Mt. Pinatubo in the Philippines erupted in 1991, for example, the sulfur dioxide it emitted did lead to temporary changes in global temperature, cooling the Earth's surface by as much as 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit over the following three years. And that eruption was 1,000 times smaller than the largest-known eruption to ever take place at Yellowstone, the Huckleberry Ridge eruption 2.1 million years ago.

Recent studies suggest that even eruptions as powerful as Yellowstone's might not trigger as extreme a cooling effect as previously thought. In 2024, researchers from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies used computer modeling to simulate an eruption on the scale of the Toba eruption in Indonesia 74,000 years ago — the largest eruption in the past 2.5 million years. Even this scale of an eruption, they predict, would only change global temperatures by roughly 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit.

Could Yellowstone erupt again?

Yellowstone's supervolcano remains active, but that doesn't mean an eruption is imminent. The region experiences frequent earthquakes, ground deformation, and hydrothermal activity, all signs that the two magma chambers beneath Yellowstone are still active. However, these geological processes are normal and there is currently nothing happening that has given scientists cause for concern. It's also important to note that geological activity doesn't run on a schedule, so even though there has been an average period of 700,000 years between major eruptions at Yellowstone, there's nothing to say that frequency will always be the same. What's more, the last time Yellowstone did erupt 70,000 years ago, it was a relatively peaceful lava flow, not an explosive, cataclysmic happening, proving that not all volcanic events have to be devastating.

More reassuringly, the infrastructure needed to keep an eye on this geological activity has only gotten better over the years. Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, a team of experts from multiple agencies across nine states in the region, closely monitor seismic activity, satellite data, and more to detect any significant changes that might indicate an eruption is on its way.

But if another significant Yellowstone eruption were to occur, the consequences would be severe, given that human civilization has built up around the supervolcano in the many thousands of years that have passed since it last erupted. However, that civilizational progress has also led to the development of volcanic monitoring and early-warning systems that provide crucial data to help keep people informed and safe. Despite the devastation that the Lava Creek eruption wrought, it was just another chapter in Earth's ever changing geological story. For more on the planet's volcanic history, learn why Europe's supervolcano could be a ticking time bomb.