Why Humans Haven't Gone Back To The Moon Since 1972

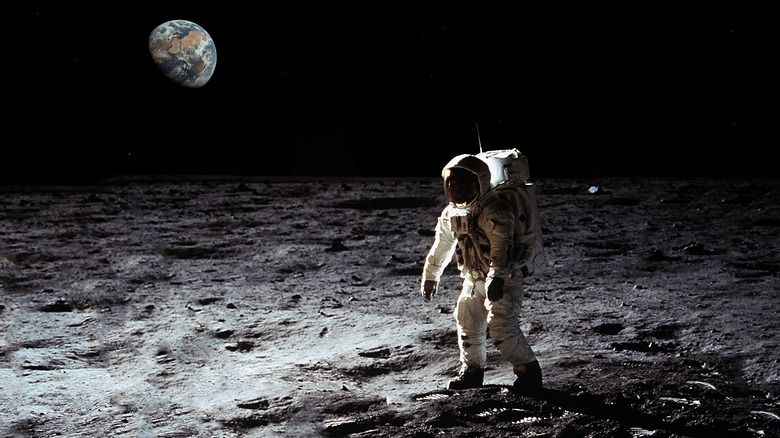

The Apollo 11 moon landing is one of the most iconic moments in human history. Commander Neil Armstrong's words, "That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind," are among the most famous ever spoken. The impact of the first moon landing reverberated around the world; it seemed as if the human species had entered an era of infinite possibility, one in which our civilization would extend to worlds beyond our own. Following the Apollo 11 landing in 1969, the United States conducted five more moon landings over the next three years, but after Apollo 17 in 1972, it stopped.

It has now been over half a century since a human being last walked on the moon. To this date, only 12 people have ever accomplished the feat, all of them American men. What happened to our aspirations of a lunar society? If we managed to land on the moon 50 years ago, surely we have the power to do it now.

Lack of technology or skilled astronauts isn't the issue. In reality, our lunar ambitions were spoiled by the same things that spoil most of life: money and politics. These concerns, coupled with the challenging climate of the moon and the rise of space stations as our primary outposts for cosmic research, have prevented another lunar landing. However, new plans have recently been revealed that seem to indicate we'll be back on the moon before too long.

Going to the moon is really, really expensive

The primary obstacle impeding a return to the moon is the budget. As you can imagine, a journey of over 200,000 miles costs a pretty penny, especially when you have to break out of Earth's atmosphere in the process. The Apollo program cost the United States $25.8 billion. Adjusted for inflation, that's over $260 billion dollars today. At the peak of its spending in 1965, NASA used more than 4% of the total U.S. federal budget, with more than three-fifths of that money going to the Apollo program.

The decline in NASA's budget actually began before the first moon landing occurred, falling steeply between 1965 and 1970. Congress was slashing the agency's funds to prioritize the Vietnam War and economic problems at home. There were originally supposed to be two more moon landings: Apollo 18 and Apollo 19, but in 1970, NASA cancelled both missions due to lack of adequate money. Today, less than 1% of federal spending goes to NASA. The agency's budget for 2025 is projected to be $25.4 billion.

The moon can be a dangerous place

Landing a human on the moon isn't just expensive; it's also a very dangerous endeavor. The fatal breakdowns of the space shuttles Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003 highlighted the fact that life is on the line every time a human takes flight, and put NASA under much greater scrutiny.

Not only is the journey to the moon a dangerous undertaking, the destination brings a horde of its own problems. The moon's heavily-cratered surface makes landing any craft challenging. Even worse, the surface of the moon is completely covered in regolith, a loose soil that gives rise to lunar dust. The dust is electrostatically charged from the solar radiation that bombards the moon, causing it to levitate slightly above the ground. Lunar dust contains sharp particles of silicate that can damage space suits and vacuum seals on equipment. Concerningly, all 12 astronauts who walked on the moon developed hay fever–like symptoms from exposure to the regolith.

Most of what NASA does regarding cosmic exploration today can be accomplished with unmanned technologies, eliminating the risk of death. Robotic rovers have been used to study the surfaces of both the moon and Mars. Meanwhile, space probes have drawn our attention all the way to the edge of the solar system.

Other space exploration projects have taken priority

NASA and other space agencies must carefully decide how to allocate their limited funds, and currently, other projects take priority over a return to the moon. The most notable of these projects have been space stations. Less than six months after the last man walked on the moon, NASA's first space station, Skylab, went into operation, remaining in orbit for almost a year. This was followed by the Space Shuttle program, which ran from 1981 to 2011, and most recently, the International Space Station (ISS), which began operation in 1998. The ISS is used for numerous experiments, and has become the primary outpost for humans beyond Earth.

The ISS is scheduled for decommission in 2030, but that doesn't mean space agencies will switch their attention to the moon. Far from it ... literally. NASA plans to contract a private company to build a replacement space station while the agency pursues an even more ambitious goal: deep space exploration. This pursuit has given rise to a number of lofty initiatives, including space stations beyond low Earth orbit and developing artificial gravity so that astronauts can stay in space for longer periods without significant health issues. Achieving these goals will be very expensive, and considering that the moon has been the most explored celestial body, it makes sense to invest in a bigger picture.

The Space Race is over

Understanding why humans haven't set foot on the moon in half a century requires an understanding of why we went there in the first place. Although the Apollo program made important discoveries, its objective wasn't really about science. The Cold War pitted the United States against the Soviet Union in a high-stakes arms race, with each country seeking to demonstrate technological superiority over the other. This soon led to the Space Race, based on the idea that whichever country could reach beyond the planet first would have cemented their position as the world's foremost superpower.

In a 1961 speech to Congress, President John F. Kennedy laid out a definitive goal for the Space Race: putting a man on the moon. In Kennedy's words, "No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind." It was that speech, and the desire for global glory, that truly led humans to the moon. NASA itself even states on its website that "The primary objective of Apollo 11 was to complete a national goal set by President John F. Kennedy."

Once that goal was achieved, putting a man on the moon no longer held much importance in the eyes of politicians or the public, whose priorities had turned to the civil unrest that gripped 1960s and '70s America. Congress ceased all funding for the Apollo program in 1974 on the grounds that its purpose had been accomplished.

There are plans to return to the moon ... eventually

In 2017, NASA revealed the Artemis program, a mission to not only return to the moon, but to build towards a sustained human presence into the future. Artemis missions will be conducted with a new type of space capsule, named Orion, which is designed to sustain a crew for up to three weeks, and powered by the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket. The mission has four planned stages, beginning with Artemis I, an unmanned test of Orion and the SLS, and culminating with Artemis IV, which will establish Gateway, the first space station to orbit the moon.

Unfortunately, the Artemis program has faced numerous delays, largely related to issues with the SLS, which was already in development before Artemis was announced, yet didn't actually launch until 2022. Artemis I was completed in the same year, but it resulted in damage to Orion's heat shield. The launch of Artemis II, a manned mission that will circle the moon, was subsequently pushed back from 2025 to 2026. Artemis III, which will be the first mission to actually put a human on the moon since Apollo 17, was also pushed back a year to 2027.

Despite delays, Artemis seems all but certain to put humans on the moon before 2030. Why that specific year? The U.S. is looking to move fast because there's another Space Race taking shape. China has announced plans to put its own astronauts on the moon by 2030, and if anything can motivate the government to push us to the moon, its competition.