How Space Permanently Damages Astronauts

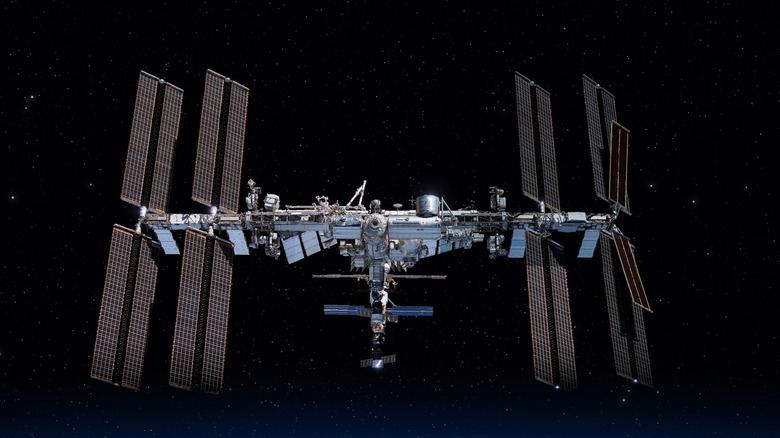

Travelling to space is just about the most epic thing a person can do, but it does come with some pretty serious consequences. There is a reason that Earth is the only place in the entire universe known to harbor life: It takes a very specific set of circumstances for an organism to survive, and space checks none of the boxes. Thanks to incredible technological advancements, we've been able to create survivable environments beyond Earth's surface, like the International Space Station (ISS) and the Space Shuttle Program, but these spaces are still a far cry from terra firma, and that presents a number of risks.

In space, astronauts are deprived of Earth's gravity, its atmosphere, and its magnetic field, which shields the planet's population from cosmic radiation. Life on the ISS lacks many of the amenities we typically rely on. There is limited space for exercise, the small sleep stations require sleeping upright, and NASA has banned astronauts from eating a number of foods on the ISS, leaving narrow options.

Staying healthy in space is a challenge, but re-adapting to life on Earth can be even tougher. Upon returning home, astronauts experience issues with balance that can leave their legs unstable for over a week. They also experience sleep issues, since the lack of a day-and-night cycle in space ruins a person's circadian rhythm. These are only the short-term issues though. The long-term consequences of space travel can be far more damaging.

Microgravity causes muscle and bone loss

Astronauts are not entirely weightless on the International Space Station. As it circles Earth in low orbit, the International Space Station is in a constant state of freefall, which creates a state of microgravity on the craft. However, the station's gravitational field is only 89% as strong as our planet's, and that 11% difference has a big impact on the human body. Microgravity places much less stress on bones and muscles compared to Earth's gravity, because they don't need to support as much weight. This is one of the rare cases in life where less stress is actually a bad thing, because without the need to resist gravity, bones and muscles quickly deteriorate.

Astronauts lose roughly 1% of their weight-bearing bone density for every month they spend in space. Upon returning to Earth, their weakened, brittle bones struggle to re-adapt to gravity, causing mobility issues and putting astronauts at a heightened risk of fractures. Recovering bone density takes a lot longer than losing it does, and astronauts who spend more than six months in space take years to return their bones to a healthy state.

In order to combat bone and muscle loss, astronauts must exercise regularly. Normal weight lifting isn't worth much in microgravity, so astronauts on the ISS use the piston-based Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED). Unfortunately, even with exercise, muscle and bone loss is inevitable because every second that an astronaut doesn't spend exercising is essentially like lying in bed.

Astronauts' hearts can shrink from weightlessness

When it comes to what NASA stands for and what it does, throughout its history, the organization has been researching the effects of space travel on the human body, and few experiments have provided more revelations than the Twins Study. Between 2015 and 2016, astronaut Scott Kelly spent 340 days on the International Space Station while his identical twin, Mark Kelly, himself a retired astronaut, remained on Earth. When Scott returned, researchers compared his condition to that of his brother and made the alarming discovery that Scott's heart had shrunk by 27%. This was due to the fact that, without Earth's gravity, the heart doesn't have to pump as hard to circulate blood, and just like the other underworked muscles in an astronaut's body, it shrinks. However, the shrinkage did not inhibit cardiac function.

Microgravity has other effects on the cardiovascular system as well. Here on Earth, the force of gravity naturally pulls our blood to our lower extremities, with the heart working to pump that blood back up. When the force of gravity is taken away, more blood pools in the upper extremities, causing astronauts to get puffy faces. Some astronauts return to Earth with hearts that show the same impacts as aging, like weakened muscles and irregular heartbeats. In some cases, these effects don't go away. Tending to astronauts' cardiovascular health is a top priority for space programs, and researchers have even begun sending bioengineered heart muscle samples to the ISS to better understand the problem.

Radiation exposure increases the risk of cancer

Space is teeming with ionizing radiation — radiation powerful enough to separate electrons from atoms. Cosmic radiation comes from stars, including the sun, and Earth is constantly being bombarded by particles originating from both inside and outside the solar system. Fortunately, Earth's magnetosphere, the magnetic field surrounding our planet and its atmosphere, shields us from most radiation; if not for it, the atmosphere would be obliterated by solar winds. But by going to space, astronauts abandon this protection.

When in low orbit, as they are aboard the ISS, astronauts still receive some protection from the magnetosphere, but it is far less effective at that altitude. Six months spent in space exposes an astronaut to approximately the same amount of radiation as taking 1,000 chest x-rays. Radiation exposure can cause cancer, as well as acute radiation sickness (ARS), which can cause a wide array of grisly effects, including loss of blood cells, electrolyte imbalance, extreme weight loss, and death.

It is very difficult to tell what the long-term effects of space radiation on astronauts are because the sample size is very small. Barely 700 people have been to space. Currently, astronauts do not appear to have especially high levels of cancer, but there are serious concerns that longer-term space flights, such as potentially traveling to Mars, could deliver a deadly dose of radiation.

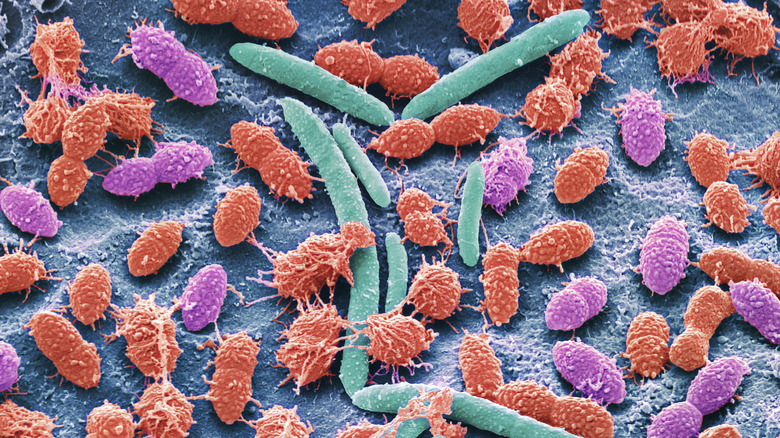

Long space flights change the gut microbiome

This might sound a little disturbing to hear, but you have an entire ecosystem of life thriving inside of your intestines right now. The human gut is home to trillions of microbes, including over a thousand different species of bacteria. These organisms have a symbiotic relationship with us, their hosts, playing an important role in digestion. They break down complex carbohydrates and fibers that our own body's can't process, they help cycle bile between the intestines and liver, and they fight against potentially harmful bacteria entering the gut, helping to keep the immune system strong. Space travel appears to change this microbiome, and scientists aren't entirely sure why.

When Scott Kelly returned from his 340 days in space, his gut microbiome showed a loss of Bacteroidetes bacteria, which play an important role in metabolism. However, it also showed heightened numbers of Firmicutes, a type of bacteria involved in breaking down complex nutrients. Other gut bacteria also decrease in space, with potential impacts on the mucous lining of the digestive tract and the ability to break down carbohydrates. Some researchers are still skeptical that space travel dramatically affects the gut microbiome because the research thus far has been limited, but unraveling this mystery will be essential if longer term space travel, such as journeying to Mars, is to become a reality.

Sterile environments weaken the immune system

Space travel doesn't just shift the gut microbiome — it weakens the entire immune system. Spacecraft such as the International Space Station are designed to be as sterile as possible, but it turns out they may be too sterile. Astronauts on the ISS have high occurrences of skin rashes and cold sores, and those who previously had chicken pox can have the virus reactivate in the form of shingles. More than half of the astronauts who participated in NASA's Apollo program got sick within a week of their return to Earth. A fresh study suggests that these detrimental effects result from a lack of biological diversity aboard spacecraft.

Research published in the journal Cell in February 2025 showed that surface swabs from the ISS contained very few microbes, the majority of which had been shed from the astronauts' skin. In order to maintain a robust immune system, the body needs to be exposed to a diverse array of microbes, training it to face the widest range of threats possible. However, aboard the ISS, astronauts receive none of the microbes found in Earth's soil and water. In order to strengthen astronaut immune systems and cut down on the rates of infections, it may be necessary to make the ISS a little bit dirtier.

Isolation has a psychological impact

Space travel doesn't just affect the body – it also takes a serious toll on the mind. Everyone experienced the effects of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, but for astronauts, that's what every day in space is like. The International Space Station is only designed for a crew of six, while the rest of humanity hangs out 250 miles below. The average ISS mission lasts for six months, during which time an astronaut's only means of communicating with their family and friends is via the internet.

Astronauts have to get along with their fellow crew members, who often hail from completely different countries, while sharing very limited space. They can't go outside for some fresh air and a walk, and their options for exercise are very limited. From the ISS, astronauts experience the sun rising and setting not once, but 16 times per day, which can make it difficult to get adequate sleep. As if all that weren't enough, the ISS is also an incredibly loud place. Living aboard the station is like living next to a highway at rush hour. Noise levels as great as that can further disrupt sleep and take an overall toll on mental health. To combat these issues, astronauts practice mindfulness, have self-care breaks in their schedule, and receive periodic care packages from home to keep their spirits up.