5 Ancient Ruins Discovered In The Most Unlikely Places

In June 2024, construction workers building a new lane on Federal Highway 105 in the Sierra Alta region of Hidalgo, Mexico, uncovered something unexpected— the base of a 1,375-year-old pyramid. According to a press statement from Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History, the foundation would have supported a complete pyramid in its day, typical of those built by Mesoamerican civilizations like the Mayans and Aztecs for ceremonial or religious purposes.

The structure appears to date to a pre-Hispanic settlement built by the Metztitlán kingdom, a multi-ethnic state that inhabited the region and that warred against — and managed to stay independent from — Aztec rule until the 16th century. While excavating the site, experts discovered 10 archaeological mounds and hundreds of ceramic and shell artifacts, providing historians a unique view into an area that was previously thought devoid of such pre-Hispanic remnants.

The finding underscores a blunt reality about the nature of ancient discoveries: They're often made by pure chance (see our list of six fossils that were hidden in plain sight for some excellent examples of this fact). And if an ancient pyramid can surface during the construction of a highway, it makes you wonder just how many other discoveries have been stumbled upon in this haphazard way. Here's a list of some of our favorites, ranging from ancient Mayan temples to underground cities.

An ancient Mayan city buried in Google Search results

Some accidental finds don't happen by digging through the dirt but by digging through the digital records of the internet. Such was the case when Tulane University anthropology doctoral student Luke Auld-Thomas discovered a massive ancient Mayan city in Campeche, Mexico, in 2024.

"I was on something like page 16 of a Google search and found a laser survey done by a Mexican organization for environmental monitoring," Auld-Thomas told the BBC. LIDAR, a laser-powered remote sensing methodology, is often used to look for structures in densely-forested regions. Auld-Thomas had come across such a survey of the Campeche region whose granular archaeological details had escaped the environmental group that had initially carried out the survey. The details of the buried city, which researchers are calling Valeriana after a lagoon located in the area, were published in the journal Antiquity in late 2024. Valeriana may have been home to as many as 50,000 inhabitants from A.D. 750 to 850 and included large buildings like temple pyramids, plazas, and a ball court, all connected by houses and other structures stretching over 10 square miles. There were also ritual structures that may have hosted Mayan sacrifices during the city's lifespan.

"Lidar is teaching us that, like many other ancient civilizations, the lowland Maya built a diverse tapestry of towns and communities over their tropical landscape," paper co-author and Thomas' advisor, Marcello Canuto, told Tulane University. Valeriana is yet more evidence that researchers are nowhere close to being able to say they've discovered all of the ancient Mayan settlements that exist.

An underground city in your basement

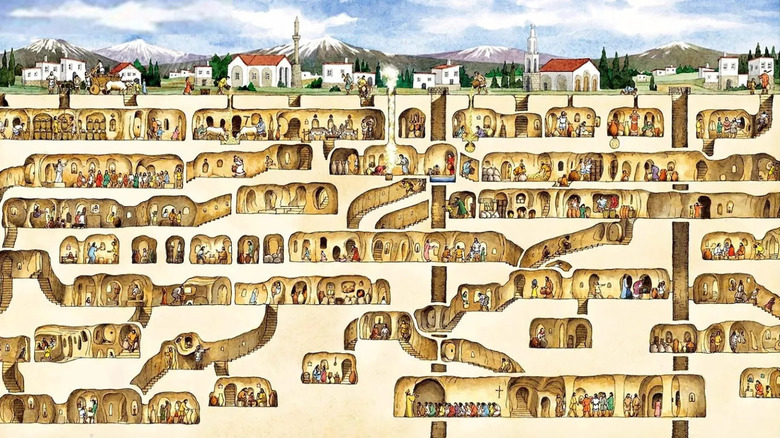

Due to its unique geographic position and rich cultural history, it's little wonder that modern-day Türkiye contains a treasure trove of ruins that crop up in the most random of ways. There's perhaps no better example of this than the discovery made by a local man in the Anatolian city of Nevşehir in 1963 when he was renovating his basement. After several of the man's chickens vanished down a small opening in the wall created during construction, he decided to investigate, eventually finding a tunnel with no end.

The man had found one of several hundred entrances to the underground city of Derinkuyu — a subterranean structure featuring an astonishing 18 levels that reach 280 feet down into the earth. The city was an engineering marvel that included rooms for sleeping and food storage as well as schools and even spaces for worship. While its origins are still up for debate, it's thought that the first tunnels were made by the Hittites around 1200 B.C. Later inhabited by the Phrygians, Persians, and Seljuks — each of which added to the city over the years — Derinkuyu would come to house some 20,000 individuals during the Byzantine Empire's rule.

But why build a city underground? The region's warring empires and factions were reason enough, and its inhabitants used it as a safe haven from invaders, like when the Byzantine Empire's Christian citizen-subjects weathered attacks from Muslim Arabs during the Arab-Byzantine wars from A.D. 780 to 1180. In the 20th century, Greeks living in Anatolia similarly used it for protection during the Greco-Turkish War before abdicating the city as Türkiye was gaining its independence in the 1920s. Hundreds of smaller underground cities exist in the region, and it's believed that they are all connected via a vast tunnel network.

A solar panel farm reveals a mysterious and violent history

Sometimes, when you're pushing into the future, you find the past. While the Spanish energy company Acciona Energía was surveying a site for a new solar panel farm in 2021, it came across the remains of a Copper Age fortress dating back 5,000 years. The fortress covers nearly 140,000 square feet, making it twice as large as the only other structure in Spain that features similar identifying characteristics. The fortification meant business, too, featuring 25 semicircular towers, three concentric walls, ditches, and a single point of entry less than 28 inches wide.

But perhaps the most intriguing thing about Cortijo Lobato — the name of the archeological site containing the fortress — is the mysterious burial it contains. Near the structure's second defensive ditch, archaeologists found what may be the remains of a Roman legionary who was buried face down with a dagger placed on his back. The burial is intriguing for several reasons, the first being that the soldier was buried there roughly 2,700 years after the structure had been abandoned in 2450 B.C. The single grave is shallow and holds the skeleton of a man in his late 20s or early 30s. The presence of a still-sheathed pugio dagger on his back (a Roman legionary standard-issue weapon), along with the fact that he was buried face down, indicates that it was a dishonorable burial.

Thousands of years before the shrouded events of the legionary's fate, the fortress experienced a violent end. Researchers discovered evidence of a devastating fire in the structure's inner doors that spread to several different areas and indicate an intentional burning. Paired with the presence of an abundance of arrowheads at the site, it's possible that a large-scale assault breached the defense's walls and led to the fortress's fiery destruction.

Byzantine shipwrecks under Istanbul

In 2004, Turkish State Railways began construction on its Marmaray rail project, a metro line that would join the European and Asian sides of Istanbul via a tunnel under the Bosphorus Strait. While examining the project's future construction site in the city's Yenikapi neighborhood in November of that year, archaeologists noticed some engraved wooden pieces beneath layers containing artifacts from the early Turkish Republic and the Ottoman Period. Deciding to expand the excavation site to learn what they were, researchers discovered something astonishing — dozens of phenomenally-preserved shipwrecks as well as the famed Theodosian Harbor from the city's Byzantine era.

The largest of Constantinople's four primary commercial harbors from the fourth to seventh century, Theodosian Harbor was a crucial center for maritime trade and shipbuilding. In total, researchers discovered 37 Byzantine shipwrecks dating from the fifth to the 11th century, providing them a new window into the slow shift from shell-based to skeleton-based shipbuilding techniques in the Mediterranean from A.D. 500 onward.

Exactly how the ships got there is a bit of a mystery that continues to elude historians. It was first proposed that 25 of the 37 vessels had sunk in a storm that wracked the Istanbul coastline, but researchers have also suggested another culprit — a tsunami. Studies have shown that some of the harbor's sediment layers may have been formed by such an event, triggered by earthquakes in A.D. 557. Apart from providing valuable insight into maritime life in Constantinople, the ships and the associated sediment layers serve as the first solid evidence of tsunamis occurring in Istanbul's Marmara Sea (for more on that watery phenomenon, check out our breakdown of when the last tsunami hit California).