Is An IQ Test Really An Accurate Measure Of Intelligence?

Can you actually quantify a person's intelligence? It's a question that has consumed the minds of psychologists, educators, employers, and politicians alike, all with their own motives. Various methods of intelligence testing have been proposed, but none have gained more attention than the intelligence quotient, or IQ, test. IQ attempts to measure a person's intelligence relative to a specific sample group by administering a series of multiple choice tests and adding up the scores.

To calculate IQ, test administrators take the cumulative score and divide it by the test subject's age before multiplying the result by 100. A score of exactly 100 represents the average score for the sample group, and any score within 15 points of 100 is considered the normal intelligence range. Scores below 70 are seen as indicators of mental disabilities, while scores over 130 are considered gifted. There is technically no limit to how high someone can score on an IQ test, but the highest results on record fall between 200–250.

People have been hired, fired, and even killed for their IQ scores, but in truth, these scores offer a very poor assessment of intelligence. There isn't even a consensus on the meaning of IQ. The pursuit of quantifying intelligence is controversial in its very nature. In seeking to measure individual intellect, there is also an inherent effort to rank one's fellow human beings. IQ tests can be a dangerously biased means of judgment, and that goes back almost as far as their origins.

The basis of IQ tests

The first modern IQ test was created in 1905 by French psychologist Alfred Binet, who had been contracted by the French government to help identify students who were likely to struggle in school by establishing a baseline for each child's intelligence level. Binet and his colleague Théodore Simon devised a 30-question test that focused not on typical academic subjects, but rather on generalized concepts of intelligence like memory and attention. They created different questions to suit a range of ages from 3–13 years, with younger students facing simpler tasks like repetition and older students dealing with more advanced concepts like sentence structure, abstract terms, and spatial reasoning.

The Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale soon gained international attention. In 1912, German psychologist William Stern released his own version of the test, which coined the term "intelligence quotient." Around the same time, intelligence tests gained traction in the United States thanks to the work of educator Henry Herbert Goddard. Goddard was the superintendent of the New Jersey Training School for Feeble-Minded Girls and Boys, and he created his own version of Binet and Simon's test to assess the potential of his students. Goddard's work became immensely influential amongst American psychologists and educators, and he went on to assess not just children in public schools, but immigrants at Ellis Island as well. Goddard was the first person to use intelligence tests as evidence in court cases. The more widespread the practice became, the more stock people put into it, which, unfortunately, they really shouldn't have.

The problems with IQ tests

The concept of intelligence testing has been deeply flawed from the get-go. Before William Stern coined the term "intelligence quotient," psychologists referred to "general intelligence" or the "G factor," hypothesizing that every person's intellectual potential is built upon this pre-set level of intelligence. Binet and Simon designed their original test to determine students' G factors, however, to this day, there is no accepted definition for what general intelligence actually means, and it's hard to trust a test that doesn't even know what it seeks to determine.

IQ tests are good at identifying a few strengths and weaknesses, but not intelligence as a whole. They are typically useful in assessing things like a person's memory capacity and how quickly they can grasp certain subjects, making them useful in some academic settings. However, IQ tests are not able to assess judgment and decision-making skills. An IQ score can't predict how a person will react to conflict, or their ability to work with others, and it ignores personality traits associated with intelligence like empathy and open-mindedness. These traits are essential for success in a collaborative society, yet many workplaces still rely on IQ tests to judge employees.

Another major flaw with IQ tests is a lack of standardization. There are over 200 different versions of the IQ test, each of which could be influenced by the biases of its creators. These biases extend to the point that IQ tests have been used to advance racist, xenophobic, and ableist agendas.

In the wrong hands, IQ tests can be dangerous

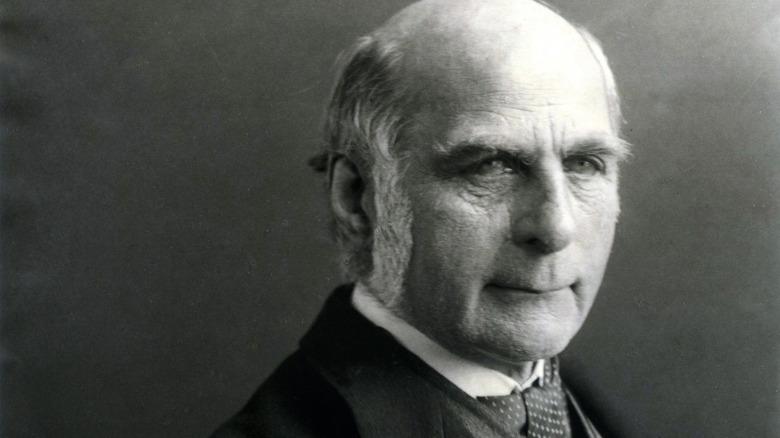

Alfred Binet was highly influenced by the English psychologist Sir Francis Galton, who was the very same man that coined the term "eugenics," the idea that intelligence is directly connected to race. Like craniology and phrenology before it, eugenics is a pseudoscience with deeply racist roots, but IQ test scores have been used on several occasions to justify it.

During WWI, the United States military implemented an IQ test created by American Psychological Association president Robert Means Yerkes, an avid believer in eugenics. Over 1 million soldiers took the test to determine where they should fit within the military hierarchy. The test questions leaned heavily on a knowledge of American culture, so unsurprisingly, immigrants who had recently arrived in the country (mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe) had the worst scores. This was used to justify a belief that those ethnic groups were inherently inferior.

In the most horrific cases, IQ tests have been used to justify forced sterilizations and murder. In 1924, the state of Virginia legalized the forced sterilization of people deemed "feeble-minded," and IQ tests were routinely used in this pursuit. In Nazi Germany, the government even legalized the murders of children who performed poorly on IQ tests. The legacy of Nazi atrocities helped steer IQ testing away from eugenics, but the issues of bias remain. With such a flawed and dangerous legacy, it may be time to move beyond our obsession with IQ.