What The T. Rex Really Sounded Like Is More Terrifying Than Jurassic Park Could Imagine

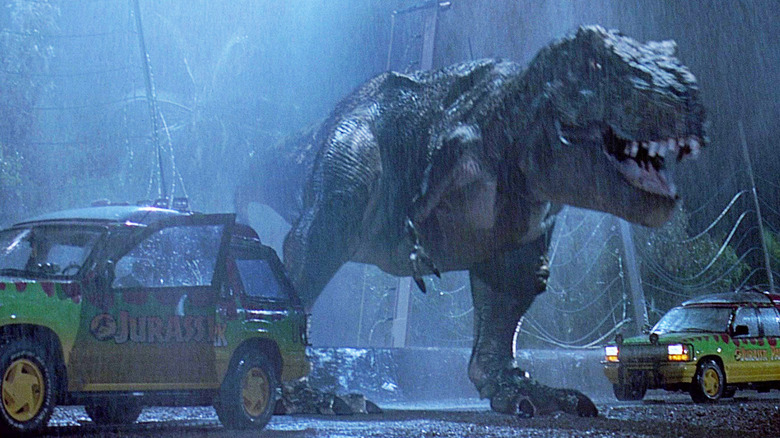

"Jurassic Park" has remained so influential since its 1993 debut that it's shaped our collective perception of dinosaurs ever since. Unfortunately for scientists who would much rather the public had a more accurate understanding of the prehistoric beasts that once roamed Earth across three distinct time periods, Steven Spielberg and his team took a lot of creative liberties with the dinos showcased in the film.

For instance, the large velociraptors that menaced Joseph Mazzello's Tim Murphy and Ariana Richards' Lex Murphy were actually based more on the Deinonychus genus of dinosaurs. In reality, raptors were much smaller than in the movie, and if we're being real sticklers, the "velociraptors" shown in "Jurassic Park" should probably have had feathers (yes, I'm aware that the dinosaurs in the movie are supposed to be genetically modified versions of their extinct forebears).

One other aspect of the movie that wasn't necessarily all that accurate was the Tyrannosaurus rex's roar. Of course, we can be a little forgiving here, seeing as the movie was trying to create an immersive theatrical experience and no human has ever heard a T. rex for themselves. Were the T. rex alive today, we would have no trouble determining how the mighty beast sounded. But it turns out that even with a lack of fossils preserving the sound-producing tissue of dinosaurs, scientists don't need the dinosaur to be alive in order to get a pretty good idea of how the T. rex might have sounded.

Fossils can't tell us how dinosaurs sounded

In "Jurassic Park," the T. rex roar is nothing short of thunderous. The result of mixing and editing together various animal vocalizations, sound designer Gary Rydstrom ultimately settled for a heavily edited combination of sounds from a baby elephant, an alligator, and a tiger to create the final version of the T. rex roar in "Jurassic Park." This was, however, a completely fanciful take on the sound of a T. rex, which not only would have sounded much different, but likely didn't roar anywhere near as much as the movie makes out.

Since most of the sound-making parts of a dinosaur's body were made up of cartilage and soft tissues such as muscle, it means that they didn't become fossilized in the way that their bones did. As such, we have no real-world examples to go off when it comes to imagining how a T. rex might sound, though some fossils do provide hints about how the dinosaurs produced sound.We know, for example, that a hadrosaur by the name of Parasaurolophus tubicen, had a long crest protruding from the back of its head which contained six hollow tubes and almost certainly acted as a resonating chamber.In order to get some idea of the noises a T. rex might make, however, scientists have to look at non-extinct animals to use as proxies for the giant reptiles that were wiped out in one of Earth's five major mass extinctions.

The T. rex's low rumble is more terrifying than a roar

When it comes to the T. rex, scientists have turned to crocodilians to understand what sounds the giant dinosaur might have made. Crocodilians are a group of reptiles that form part of the Archosaur lineage, which also includes dinosaurs and birds. The animals in this group, which includes alligators, crocodiles, and caimans, actually produce a strong rumble while keeping their mouths closed, and scientists theorize that it's possible the T. rex could have done the same, though in a much more impressive capacity.

Professor Julia Clark of Texas University has been carrying out research in this field, looking at not just crocodilians but dinosaurs' other evolutionary cousins, birds. In BBC documentary, "The Real T-Rex," Clark is shown using the call of the Eurasian bittern and a rumble produced by a Chinese alligator and pitching them down to create an approximation of what the T. rex might have sounded like. The ominous reverberation is arguably even more terrifying than the T. rex roar of "Jurassic Park," and as the pitch continues to drop, it approaches infrasound, a form of sound where the waves vibrate so slowly humans struggle to hear them.

As the paleontologist explained to the BBC, "[T. rex] wouldn't have [roared], especially not just before attacking or eating their prey. Predators don't do that." Instead, they would have produced this low rumbling sound by inflating the soft tissues of their throats, though Clark does note that the dinosaur could have used open-mouth calls in other situations. Otherwise, it's highly likely that the real T. rex emitted this menacing rumble while stalking the Cretaceous period.