A Killer Is Back: Here's Everything You Need To Know About The Record-Breaking Measles Outbreak

One of history's longest-enduring illnesses is rearing its ugly head again in the United States, decades after a safe and effective vaccine emerged and 19 years after the disease was declared eliminated.

It's only April, but already this year the country has seen 555 cases of measles, the second-highest number of cases in 25 years. With eight more months to go in 2019 and no signs of the disease slowing down, public health officials around the country are worried.

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio has declared a public health emergency. The declaration ordered residents of the Williamsburg neighborhood, where there have been more than 250 cases since September of 2018, to get vaccinated immediately. He warned that anyone who doesn't comply could face consequences, including $1,000 fines and school closings.

New Jersey, Washington and California have also been hit especially hard. In other parts of the world, countries including Ukraine, Madagascar, India, Pakistan and Yemen are also experiencing record numbers of cases.

While the measures may seem extreme, officials feel they must crack down on a disease so easily spread. Measles is wildly contagious — stick a patient in a room with people who are not yet vaccinated or not immune to the disease, and up to 90 percent of them would contract the disease. And if that patient coughs or sneezes in that room? Someone else could walk in up to two hours later and still pick up measles. What's more, that patient could spread the disease for four days before they even realize they're infected.

Once infected, measles usually starts with symptoms similar to a common cold, like a fever, cough and fatigue. A few days after that comes the rash — it's dry, itchy and often covers the entire body in tiny red spots. Today in the U.S., many patients recover without lasting effects. But in some cases, especially in parts of the world lacking medical resources and treatment, measles can lead to serious complications including hearing loss, pneumonia and encephalitis, or swelling of the brain.

Wait, I Thought No One Got Measles Anymore?

Wait, I Thought No One Got Measles Anymore?

You thought wrong. But it is less of a problem than it used to be, thanks to a vaccine that started being distributed in the United States in 1963. Before the vaccine, measles killed millions of people over several centuries and continents, often during massive outbreaks where invaders who had developed a resistance to the disease introduced it to new communities.

Contact with Europeans led to a measles outbreak that decimated Hawaii in 1848, killing as much as one third of the population. Fiji also lost a third of its population in just six short months in 1875, after a Fijian chief brought it back to the islands following a trip to Australia. Cuba was hit even worse in 1529, when an outbreak spread by Spanish colonizers killed two out of every three native people (many of whom had already survived smallpox, another killer the conquistadors brought with them).

Officials in the U.S. first started tracking measles in 1912. Over the next 10 years in the States, about 6,000 people died of measles each year. Prevention improved over the next few decades in the U.S., but in the years before the vaccine debuted, it was still infecting millions and killing hundreds of U.S. children each year. Globally, about 2.6 million died around the world each year.

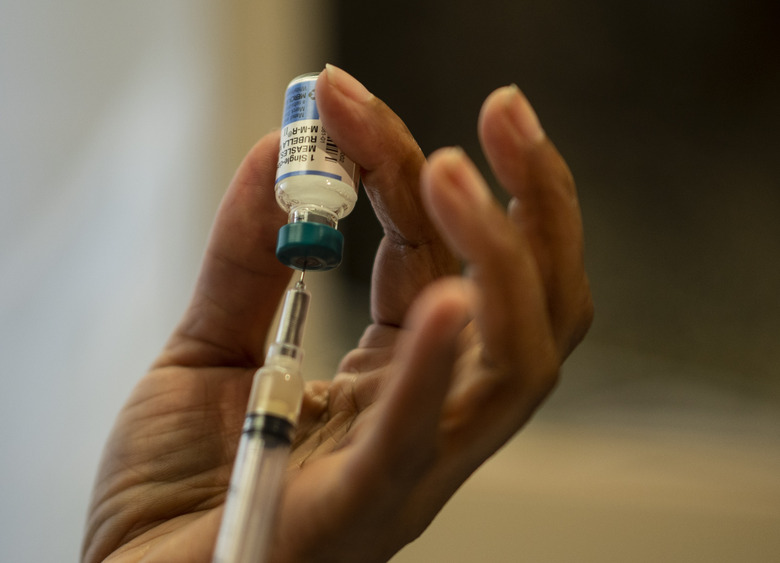

Then, scientists developed a vaccine and began distributing it in 1963. It changed everything. Global public health campaigns to vaccinate children within a year of their birth drastically cut back on the number of measles cases each year. In 2000, about 72 percent of the world's kids got a dose of the vaccine by their first birthday, and by 2017, that number jumped to 85 percent. The Center for Disease Control estimates that vaccination push is responsible for an 84 percent drop in measles cases and the prevention of more than 20 million deaths worldwide from 2000 to 2016.

Sooooo ... Why is it Back?

Sooooo ... Why is it Back?

In many parts of the world, poverty, civil unrest and insufficient medical resources have made it difficult for children to be vaccinated, making outbreaks more common.

In other developed countries, though, such as the United States and Israel, some people are opting out of vaccinations. You might be asking yourself, why would anyone do that? Great question. Anti-vaxxers, as they are becoming colloquially known, give several reasons to choose not to vaccinate their children, ranging from religion to completely debunked claims that vaccines cause autism. Others believe that vaccines contain too many toxins.

When it comes to the measles vaccine, herd immunity is important. When less than 90 percent of the population gets immunized, outbreaks turn from hypothetical scenarios to very real disease and death. That means that none of the reasons vaccine skeptics give are good enough to justify exposing anyone to a disease that still kills more than 100,000 people each year.

Even if vaccines did contribute to autism (which they absolutely do not!), autism doesn't kill. As for toxins, the FDA has ruled that any seemingly unsafe ingredients in vaccines are in amounts low enough to cause no harm.

Measles, on the other hand, is bringing record-breaking amounts of harm to kids both in the U.S. and around the world. Know your facts about the power of immunization in case you run into someone who might have false information — sharing them could just save a life.

Cite This Article

MLA

Dragani, Rachelle. "A Killer Is Back: Here's Everything You Need To Know About The Record-Breaking Measles Outbreak" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/a-killer-is-back-heres-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-record-breaking-measles-outbreak-13718359/. 17 April 2019.

APA

Dragani, Rachelle. (2019, April 17). A Killer Is Back: Here's Everything You Need To Know About The Record-Breaking Measles Outbreak. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/a-killer-is-back-heres-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-record-breaking-measles-outbreak-13718359/

Chicago

Dragani, Rachelle. A Killer Is Back: Here's Everything You Need To Know About The Record-Breaking Measles Outbreak last modified August 30, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/a-killer-is-back-heres-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-record-breaking-measles-outbreak-13718359/