Cancer Chameleons: How Some Aggressive Cancer Cells "Hack" Chemotherapy

Every year, cancer kills more than 500,000 Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and remains the number two cause of death worldwide. And while research has developed diagnostic tools and therapies that make early diagnosis and aggressive treatment more effective than ever, cancer still kills in part because of drug resistance.

But why do cancer cells become so resistant to treatment? Read on to learn more about what's happening in the cell during cancer development, as well as during chemotherapy, and the exciting new discovery that could shape the way people treat aggressive cancers.

How Mutations Drive Cancer Growth

How Mutations Drive Cancer Growth

While there are hundreds of types of cancers, which can affect virtually any tissue in your body, they all start as a result of genetic mutations. Our cells naturally have genetic safeguards that protect against uncontrolled growth. Some genes serve as "guards" or checkpoints and prevent the cell from moving into the next phase of growth if there's something wrong. Others proofread DNA after synthesis to find and correct errors. Still others help the cell carry out planned cell death (apoptosis) if it's no longer healthy, making room for other healthy cells to grow.

Mutations in any of the genes that slow growth, proofread DNA or allow for apoptosis can contribute to cancer. As one safeguard breaks down, such as the ability to proofread DNA, the cells develop mutations even more quickly. Over time, this allows the cells to divide faster and faster, causing cancer.

How Chemotherapy Targets Cancer

How Chemotherapy Targets Cancer

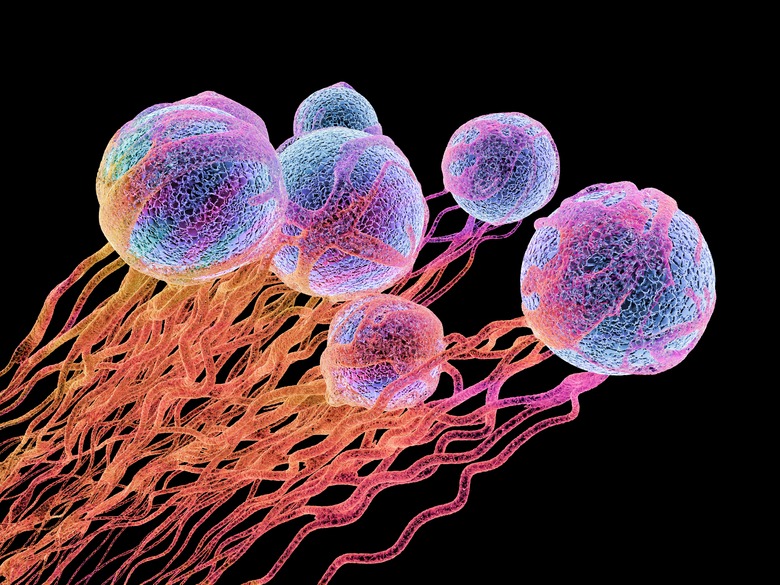

Many chemotherapy agents work with a simple rationale: By targeting the cells in the body that grow the fastest, you naturally target cancer cells. Chemotherapy drugs might stop cells from dividing properly, trigger apoptosis or help "starve" the cancer cells by preventing them from developing their own blood supply.

A chemotherapy drug might disrupt one of dozens of pathways for cancer growth. That's why doctors often recommend a mix of chemotherapy drugs to disrupt several pathways at once and why cancer cells can become resistant to a chemotherapy drug, if they develop a mutation that allows it to "bypass" that pathway.

So Where Do Cancer "Chameleons" Come In?

So Where Do Cancer "Chameleons" Come In?

Since mutations allow cancer cells to bypass chemotherapy drugs that would otherwise stop cell growth in its tracks, there is a strong selective pressure for cancer cells who can "shape-shift" to become resistant to chemotherapy.

What scientists are now discovering, though, is just how much they can shift, and how they do it.

New research, published in Developmental Cell in 2018, analyzed the genetics of thousands of samples of small-cell lung cancer, which is a type of cancer that's particularly aggressive because of its resistance to chemotherapy, to look for trends and patterns The researchers found that the cells lacked a gene called NKX2-1, a gene that would normally guide cells as they develop into healthy lung cells.

When the researchers dug deeper into how the loss of NKX2-1 might work in lung cancer, they found that the cancer cells actually shifted to take on the characteristics of stomach cells, to the point that the cancer cells secreted digestive enzymes.

What Does It Mean for Cancer Treatment?

What Does It Mean for Cancer Treatment?

The researchers speculate that this is a new way for cancer cells to gain chemotherapy resistance by hiding in plain sight, disguised as another type of tissue. Think about it: If doctors prescribe chemotherapy for lung cancer, then cancer cells that can "hide" by looking like stomach tissue have a better chance of evading chemotherapy. Understanding just how cancer cells shape-shift might allow researchers to create better drugs to target them.

However, there's still a lot people don't know. Can several types of cancer shape-shift in this way? Which other genes are involved? How easily can those shape-shifted cells mutate yet again to stay resistant?

While it may take years to answer those questions, every discovery brings us closer to understanding all that goes on in our cells during cancer, and the best way to work toward cures.

Cite This Article

MLA

Tremblay, Sylvie. "Cancer Chameleons: How Some Aggressive Cancer Cells "Hack" Chemotherapy" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/cancer-chameleons-how-some-aggressive-cancer-cells-hack-chemotherapy-13711546/. 18 June 2018.

APA

Tremblay, Sylvie. (2018, June 18). Cancer Chameleons: How Some Aggressive Cancer Cells "Hack" Chemotherapy. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/cancer-chameleons-how-some-aggressive-cancer-cells-hack-chemotherapy-13711546/

Chicago

Tremblay, Sylvie. Cancer Chameleons: How Some Aggressive Cancer Cells "Hack" Chemotherapy last modified August 30, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/cancer-chameleons-how-some-aggressive-cancer-cells-hack-chemotherapy-13711546/