What Are Convection Currents?

One of the first things you probably learned in physics class was the law of conservation of mass, which at the most basic level means that mass can neither be created nor destroyed. The same applies to energy. All of the energy that exists in the entire universe arose from the Big Bang, but it has since spread far and wide because, while energy cannot be created, it can be transferred in many ways, one of the most important being convection currents.

Convection currents are a means of transferring thermal energy — the type of energy that causes things to change temperature. Thermal energy can be transferred from molecule to molecule in three ways: radiation, conduction, and convection. Radiation is the transfer of energy via electromagnetic waves, which is best exemplified by the sun heating our planet. Conduction is the transfer of energy between solids, like when you burn your hand on a hot pot or pan. Convection fills in the rest, transferring energy through both liquid and gaseous matter.

In the simplest terms, convection is the transfer of heat through currents in a fluid. Consider a tea kettle. When you put the kettle on the stove, the water at the bottom, closest to the burner, heats up first. Hot water is less dense than cold water — same for air and other fluids — which causes it to rise to the top of the kettle. The rising hot water pushes cold water from the top of the kettle down, so that it too heats up.

Convection currents cycle air in the atmosphere

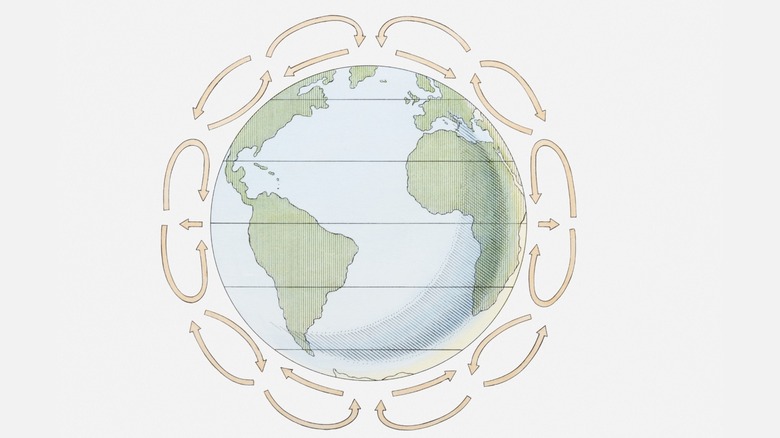

Convection is a term that comes up often in weather reports, and it is essential to understanding what happens in Earth's atmosphere. Air is constantly moving around Earth, a phenomenon known as atmospheric circulation. This circulation is the direct result of convection currents, which carry warm air from the region around the planet's equator towards poles. This occurs in atmospheric subdivisions known as wind cells.

Between the equator and 30th parallels (both north and south), there are two bands known as Hadley Cells. Between the 30th parallels and the poles are another pair of cells known as Ferrel or Mid-latitude Cells. Finally, there are cells at each pole. Each of these cells is a convection current, cycling warm and cool air. Because each cell is essentially an enclosed system, air from the equator never actually reaches the poles, hence the temperature extremes associated with those higher latitudes.

Wind, clouds, and storms are all shaped by convection

If you've ever been caught in the rain, or had your cap whisked away by the wind, you can blame convection currents. As currents carry warm air upward, they leave pockets of low pressure behind. Cold air currents then rush in to fill those low pressure pockets, and we feel that movement in the form of wind. The more extreme the pressure difference is, the stronger the wind blows.

Convection currents also play a role in forming clouds, specifically the fluffy-looking cumulus and cumulonimbus clouds. These are created when convection currents lift air from close to Earth's surface up to higher altitudes. This process of convection can cool the air so much that water vapor within it condenses into clouds. Rising cumulus clouds are well-known warning signs of thunderstorms, which are also influenced by convection currents. Storm clouds swell continuously as long as convection currents continue to push hot air upwards. It is only after rainfall cools the air below that this cycle stops and the clouds dissipate.

There is even a specific type of rainfall associated with convection currents known as convective precipitation. It occurs when cumulus clouds accrue enough cloud droplets to condense into precipitation. Because of the high amounts of energy being cycled through convection currents, convective precipitation tends to come in short, heavy spurts. If you've ever been through a summer thunderstorm, you've experienced this effect of convection currents firsthand.