How The Elements Are Classified On The Periodic Table

The periodic table, which contains all the naturally occurring and mad-made chemical elements, is the central pillar of any chemistry classroom. This method of classification dates to a textbook from 1869, written by Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev. The Russian scientist noticed that when he wrote the known elements in order of increasing atomic weight, he could easily sort them into rows based on similar characteristics. Amazingly, the similarities were so distinctive that Mendeleev was able to leave spaces for several undiscovered elements in his periodic classification.

Periodic Organization

Periodic Organization

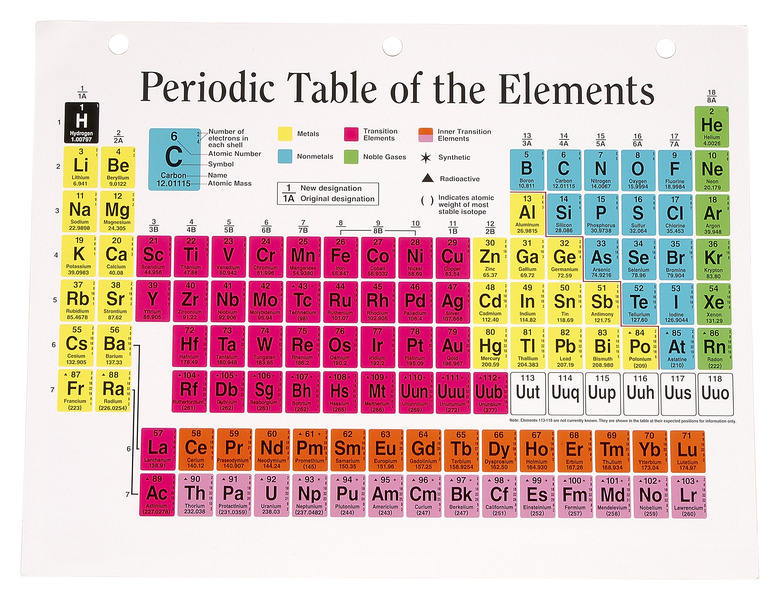

In the periodic table, an element is defined by its vertical group and horizontal period. Each period, numbered one through seven, contains elements of increasing atomic number. Unlike Mendeleev's original list, the modern periodic table is based on atomic number, or the number of protons in an element's atomic nucleus. The proton number is a logical choice for organizing the elements, since protons determine the chemical identity of an atom, while atomic weight varies with different atomic isotopes. Eighteen columns are in the periodic table, usually referred to as groups. Each group contains several elements that have similar physical properties due to their underlying atomic structure.

Scientific Rationale

Scientific Rationale

The atom is the smallest division of matter that maintains its identity as a chemical element; it is of a central nucleus surrounded by an electron cloud. The nucleus has a positive charge due to the protons, which attract the small, negatively charged electrons. The electrons and protons are equal in number for a neutral atom. The electrons are organized into orbitals or shells due to the principles of quantum mechanics, which limit the number of electrons in each shell. Chemical interactions between atoms usually affect only the outer electrons in the last shell, called the valence electrons. The elements in each group have the same number of valence electrons, making them react similarly when they gain or lose electrons to other atoms. The electron shells increase in size, causing the increasing period size of the periodic table.

Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metals

Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metals

The far left side of the periodic table includes two groups of highly reactive metals. With the exception of hydrogen, the first column consists of the soft, shiny alkali metals. These metals have only one electron in their valence shell, which is easily donated to another atom in chemical reactions. Because of their explosive reactivity in both air and water, the alkali metals are rarely found in their elemental form in nature. In the second group, the alkaline earth metals have two valence electrons, making them slightly harder and less reactive. However, these metals are still rarely found in their elemental form.

Transition Metals

Transition Metals

The majority of elements in the periodic table are classified as metals. The transition metals lie in the center of the table, spanning groups three through 12. These elements are solid at room temperature, except mercury, and have the metallic color and malleability expected of metals. Because the valence shells grow so large, some of the transition metals are excerpted from the periodic table and appended to the bottom of the chart; these known as the Lanthanides and Actinides. Many of the transition metals near the bottom of the periodic table are rare and unstable.

Metalloids and Nonmetals

Metalloids and Nonmetals

On the right side of the periodic table, a rough diagonal line divides the metals on the left from the nonmetals on the right. Straddling this line are the metalloids, such as germanium and arsenic, which have some metallic properties. Chemists categorize all elements to the right of this dividing line as nonmetals, with the exception of group 18 on the far right. Many of the nonmetals are gaseous, and all are notable for their tendency to gain electrons and fill their valence shells.

Noble Gases

Noble Gases

Group 18, on the far right side of the periodic table, is composed entirely of gases. These elements have full valence shells, and tend to neither gain nor lose electrons. As a result, these gases exist almost exclusively in their elemental form. Chemists classify them as noble or inert gases. All the noble gases are colorless, odorless and nonreactive.

Cite This Article

MLA

MacIntosh, Mary. "How The Elements Are Classified On The Periodic Table" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/elements-classified-periodic-table-11404105/. 24 April 2017.

APA

MacIntosh, Mary. (2017, April 24). How The Elements Are Classified On The Periodic Table. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/elements-classified-periodic-table-11404105/

Chicago

MacIntosh, Mary. How The Elements Are Classified On The Periodic Table last modified August 30, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/elements-classified-periodic-table-11404105/