What Are The Functions Of A Liver Cell?

The challenge with liver cells is that they get lonely very fast, making them very temperamental when they're outside the body. "Liver cells have been notoriously finicky," MIT engineering professor Sangeeta Bhatia, M.D., told Forbes Magazine in March 2009. She adds, when you take liver cells out of the body, "The cells are dying immediately, and function is lost on the order of hours." Researchers posit that they can use liver cells to create new livers for more than 16,000 patients on the liver transplant list, to develop vaccines for hepatitis C and malaria and to create better toxicity tests for new drugs–if only these liver cells would cooperate!

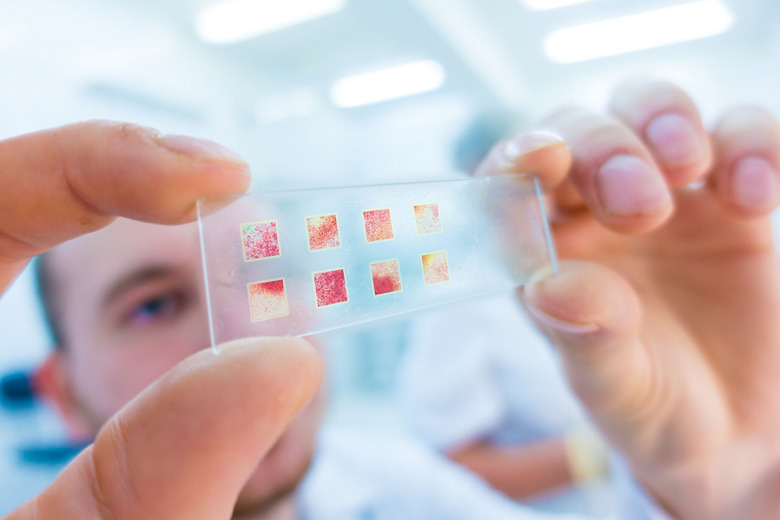

Hepatocytes

Hepatocytes

It's no secret that liver cells are socialites that know how to throw a party. They like to have a number of supporting cells around them at all times. Hepatocytes (also called parenchymal cells) are the head honchos. These popular cells make up 70 to 80 percent of the liver's cytoplasmic mass and are involved in synthesizing protein, cholesterol, bile salts, fibrinogen, phospholipids and glycoproteins. In other words, hepatocytes ensure that our blood coagulates so we don't bleed to death, that cell communication is tip-top and that we are able to carry fats in the bloodstream. Other functions of the hepatocytes include the transformation of carbohydrates (from alanine, glycerol and oxaloacetate), protein storage, start of the formation and secretion of bile and urea, and detoxification and excretion of substances. Thanks to these main cells, we are able to fight off disease, produce waste, transport materials throughout the body and process everything from drugs and insecticides to steroids and pollutants.

Liver Endothelial Cells (LEC)

Liver Endothelial Cells (LEC)

Another type of liver cell is the endothelial cells. Since they do not have tight membranes, these cells act as "scavengers" of nearby cells– ollecting and circulating hepatocytes in the blood, for instance. They're also chiefly responsible for transporting white blood cells and other material from the blood to the liver and for increasing the immune system's tolerance of the liver. They can absorb ligands, which serve as biological markers and binders for pharmaceutical drugs. When stimulated, endothelial cells secrete cytokines, which is a form of cellular communication signal.

Kupffer Cells (KC)

Kupffer Cells (KC)

Kupffer cells are located within the sinusoidal lining of the liver and hold a quarter of the liver lysosomes. The lysosomes digest and dispose of dying cells, unnecessary proteins, bacteria and foreign microbes. If stimulated, kupffer cells secrete mediators of the immune response system, and they can perform a complex array of functions–from disarming foreign substances to removing damaged red blood cells from circulation. In a way, the kupffer cells are like bodyguards and assassins for the hepatocytes, protecting them from invaders and cell refuse.

Hepatic Stellate Cells (HSC)

Hepatic Stellate Cells (HSC)

Think of the hepatic stellate cells as the liver's reserve army. Most of the time, this 5 to 8 percent of the liver's cells just sit around in an inactive "quiescent" state, storing vitamin A and a number of important receptors. Yet when activated (by an event like liver injury), the cell promotes ion movement, the production of antibodies, genesis of natural killer T-cells and the proliferation of chemical responses to stress. Researchers believe that hepatic stellate cells play a key role in releasing collagen scar tissue and encouraging liver scarring.

Other Cells

Other Cells

Other cells hanging out in the liver include epithelial cells of bile duct, endothelial cells of blood and lymphatic vessels, smooth muscle cells of arteries and veins, nerve cells, fibroblasts and inflammatory cells. This matrix of cells all working together is what really facilitates functionality in the liver. By cooperating, they can filter the blood, store vitamins and minerals, excrete harmful toxins, produce bile, transport materials, form compounds that help coagulate the blood and metabolize carbohydrates, fats and proteins.

Significance

Significance

The functions of liver cells are very significant in medical research today. Currently, scientists are examining transplanted hepatocytes in hopes that they'll find their way to an injured liver, repair, remove waste and reproduce–thus negating the need for donor livers. Hepatocytes are the focus of hemophilia research as well, since they play such a key role in blood coagulation. They're also looking at how hepatocyte death and stellate cell proliferation contribute to inflammation, fibrosis and even cancer. Endothelial cells are being studied to search for ways to target liver injury with pharmaceutical drug treatments. Endothelial cells also promote early liver and pancreas formation, so unlocking the key as to how these cells work together to grow a new organ will answer many questions in the years to come.

Cite This Article

MLA

Fusion, Jennn. "What Are The Functions Of A Liver Cell?" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/functions-liver-cell-5106552/. 13 March 2018.

APA

Fusion, Jennn. (2018, March 13). What Are The Functions Of A Liver Cell?. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/functions-liver-cell-5106552/

Chicago

Fusion, Jennn. What Are The Functions Of A Liver Cell? last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/functions-liver-cell-5106552/