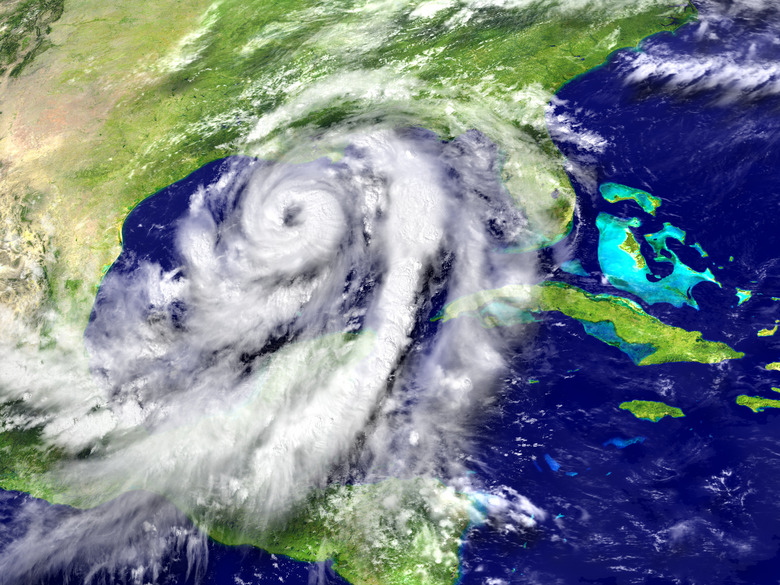

How Long Does It Take For A Hurricane To Travel Over Land?

A category 5 hurricane reaches destructive wind speeds, as high as 157 miles per hour, but once it makes landfall, its forward speed may only be 10 mph. The forward speed of a hurricane does not equate to its wind speed, it represents the pace at which it travels across the landscape. Hurricanes can also include the destructive effects of storm surges that inundate coastlines; inland flooding from heavy rainfall and tornadoes spawned by the ferocity of the storm. The longer that hurricanes remain over land can amplify these destructive effects, but generally only to a limited extent.

TL;DR (Too Long; Didn't Read)

Hurricane strength gets rated based on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale , a 1 to 5 rating founded on its sustained wind speed. Category 1 and 2 hurricanes have wind speeds that range from 74 to 110 mph. Category 3, 4 and 5 hurricanes cause the most damage with wind speeds that range from 111 to 157 mph or higher.

Forward Speed

Forward

Speed

As powerful and dangerous storms that form over tropical waters and can strike land areas in their path with deadly force, hurricanes bring with them extremely high, sustained winds above 74 mph and possibly reaching upwards of 157 mph. Forward speeds of hurricanes generally average from 10 to 35 mph, depending on the latitudes, with the fastest-moving storms occurring at the highest latitudes. For example, hurricanes impacting New England, for instance, tend to move more quickly than hurricanes striking Cuba. Hurricanes can also remain stationary for a while, as did Hurricane Mitch over Honduras in 1998.

Landfall Signals Death Knell

Landfall

Signals Death Knell

Although there are extremely rare exceptions, landfall equals the ultimate demise of most hurricanes. Hurricanes weaken over land because they are fueled by evaporation from warm ocean water, which dry land surfaces do not provide. After only a few hours over land, hurricanes begin rapidly to deteriorate, with wind speeds decreasing significantly. If they remain over land long enough, they are eventually absorbed into other weather systems or dissipate entirely.

Land Mass Size

Land Mass Size

The time it takes a hurricane to travel over land depends partially on the size of the landmass involved. Hurricanes appear to race through small island groups, such as the Cayman or Virgin Islands, with extreme swiftness, simply because the islands don't encompass a great deal of land.

Hurricanes tend to track across Florida relatively quickly also, since it is a peninsula surrounded by water on three sides. In contrast, because of the extensiveness of the North American continent, hurricanes on northward tracks striking the central Gulf Coast spend longer time over land. Hurricanes can strike multiple land areas — particularly islands or peninsulas, such as the Bahamas, Florida and the Outer Banks — and regain strength again over the ocean after each brief encounter with land.

Significant Variability

Significant

Variability

All told, the time it takes a hurricane to travel over land can vary from multiple days to mere hours. Depending on myriad meteorological factors, certain hurricanes may barely move over land or even stall entirely; Hurricane Mitch sat over Honduras for nearly a week, causing catastrophic loss of life. Hurricanes may also combine with non-tropical weather systems, such as fronts or troughs of low pressure, producing drenching rains for an extended period, as did Hurricane Agnes in the Mid-Atlantic in 1972.

Some hurricanes never make landfall entirely, merely skirting coastlines so that their eyewall remains entirely at sea. Depending on the girth, distance from land and intensity of such storms, coastal land areas may experience anything from light rain bands and higher-than-normal tides to damaging floods and intense storm surges. And hurricanes don't necessarily travel over land at all. Many never make landfall, completing their entire life cycle — from formation to dissolution — over the open ocean, such as powerful Hurricane Linda in the Eastern Pacific in 1997.

Cite This Article

MLA

Harris, Amy. "How Long Does It Take For A Hurricane To Travel Over Land?" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/long-hurricane-travel-over-land-12327531/. 23 April 2018.

APA

Harris, Amy. (2018, April 23). How Long Does It Take For A Hurricane To Travel Over Land?. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/long-hurricane-travel-over-land-12327531/

Chicago

Harris, Amy. How Long Does It Take For A Hurricane To Travel Over Land? last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/long-hurricane-travel-over-land-12327531/