Methods To Create Opals In A Lab

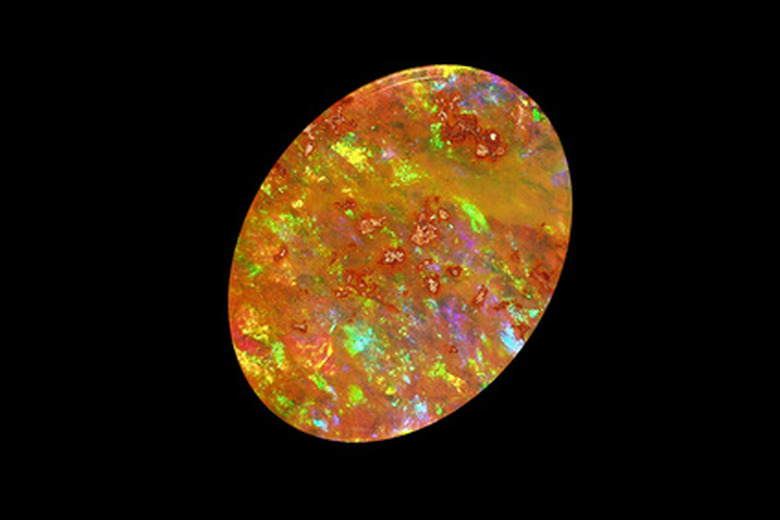

Opal is made of hydrated silica, or silicon dioxide. Its water content varies. Natural opals come in two varieties. Common opals are a single color, and they can be transparent, white, red or black. The other variety, gem-quality opal, is called precious opal. Precious opals are known for their play of color, the rainbow that shimmers as it is turned in the light. Researchers who work on creating opals in the lab try to capture this elusive quality and recreate the beauty of natural precious opals. Three categories of opals are created in the lab: imitation, synthetic and artificially grown.

Imitation Opals

Imitation Opals

The only requirement for a material to be a successful imitation opal is to look like natural opal. John Slocum invented an imitation opal known as Slocum Stone, or opal essence, in 1974. The stone is made of glass with bits of metallic foil that create the fire that is characteristic of opal. Opalite is another imitation that is made of plastic. It is softer than natural opal and exhibits lizard-skin iridescence, a scale-like pattern that is close to the appearance of natural opal but is still noticeably different.

Synthetic Opals

Synthetic Opals

The basic process of opal synthesis consists of three stages. First, scientists create tiny silica spheres. Next, they arrange the spheres in a lattice pattern to imitate the structure of precious opal. Finally, they fill the pores of the structure with silica gel and harden it. The process can take more than a year. The result is a hydrated silica product that exhibits iridescence and has a similar appearance to that of natural opal. The most difficult part of opal synthesis is recreating the rainbow fire of natural precious opal. Pierre Gilson created the first synthetic opal in 1974, and the early attempts had bands of iridescence rather than sparkles. Researchers adjusted the process and created lizard-skin iridescence.

Len Cram’s Opal Growing Method

Len Cram's Opal Growing Method

In the 1980s, the opal photographer and historian Len Cram began experimenting with new ways to grow opals. After hearing stories of opalized skeletons and fence posts around opal mines, Cram doubted the traditional explanation of opal formation. Others hypothesized that silica filled in pockets in the ground and hardened into opal over hundreds of years. Cram believed that opals grew more quickly. He thought that opals formed from chemical reactions involving compounds in the dirt. Cram has created his own process for creating opals based on this theory. He mixes opal dirt with liquid electrolytes, and within months he grows opals that are visually indistinguishable from natural opals.

Cite This Article

MLA

DeLee, Danielle. "Methods To Create Opals In A Lab" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/methods-create-opals-lab-7330256/. 24 April 2017.

APA

DeLee, Danielle. (2017, April 24). Methods To Create Opals In A Lab. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/methods-create-opals-lab-7330256/

Chicago

DeLee, Danielle. Methods To Create Opals In A Lab last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/methods-create-opals-lab-7330256/