The Oil Immersion Lens Needed To View Bacteria

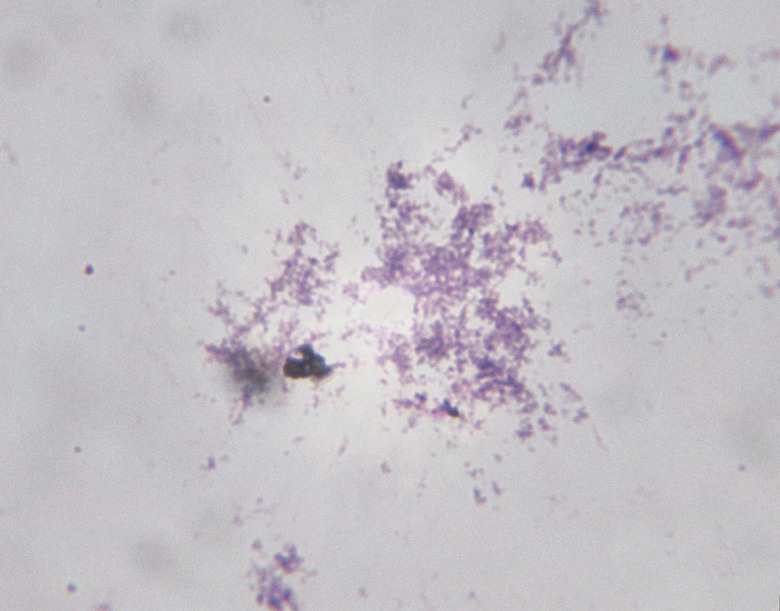

The light microscope is an essential tool of the bacteriologist. Bacteria are simply too small to see unaided. Some bacteria are so small, in fact, that they can't even be seen with a powerful light microscope without a little help — a little help in the form of an oil immersion lens. The lenses that require oil immersion are all classified as high magnification objectives.

Magnification of the Eye

Magnification of the Eye

Your eye contains surfaces that bend light to bring it to focus on your retina. The position of a spot of light on your retina depends upon the angle at which the light enters your eye. Your eye focuses light from two different angles at two different spots. The separation of the spots depends upon the difference in the angle. If two spots are close enough together that they stimulate the same cells on your retina, you won't be able to tell them apart. That's why you can't see bacteria: the angle between light coming from the two sides of a bacterium is so tiny that your eye blends it in with other light.

How a Microscope Works

How a Microscope Works

A microscope is like an extra lens in front of your eye. The whole purpose is to magnify the angle of light coming from an object, so the microscope acts like one big magnifying glass, bending light to make it appear as if the object is spread out. But using one big lens for the job would create dim and distorted images, so a microscope uses a couple of small lenses: an objective close to the sample and an ocular, or eyepiece, close to your eye. Each of those lenses has its own magnification. The magnification of the entire microscope is the product of the magnification of both lenses. A 10X ocular — one that magnifies by a factor of 10 — with a 20X objective gives an overall magnification of 200X.

Bending Light

Bending Light

Light bends when it transitions from one surface to another. Two things are necessary: the light needs to strike the interface at an angle, and the "density" of the two materials needs to be different. This is not actually density by weight, but a kind of optical density called the index of refraction.

The higher the magnification, the greater the angle of light the objective must collect from the sample. Normally, bacteria are in a drop of water contained in a glass slide, and light bends as it leaves the slide. This has the effect of making a cone of light coming from the bacteria spread to an even larger cone. At high magnifications the cone of light must get large — so large that it can miss the lens altogether. That's where oil immersion comes in.

Oil Immersion Lenses

Oil Immersion Lenses

The light cone from a glass slide spreads out for two reasons: because it's at an angle with respect to the surface and because the index of refraction of the air is lower than the index of refraction of the glass. Oil has the same index of refraction as the glass, so the cone of light does not spread out too much. Instead, light stays at the same angle until it reaches the objective lens.

The objective lens must be specially designed to focus on a sample through the oil, but many lenses are designed this way. Generally, objective lenses of 60X or greater might use oil — and they certainly will by the time you reach 100X. Because oculars are typically 10X, oil is necessary for viewing bacteria at a magnification of 1000X.

Cite This Article

MLA

Gaughan, Richard. "The Oil Immersion Lens Needed To View Bacteria" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/oil-immersion-lens-needed-bacteria-19559/. 24 April 2017.

APA

Gaughan, Richard. (2017, April 24). The Oil Immersion Lens Needed To View Bacteria. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/oil-immersion-lens-needed-bacteria-19559/

Chicago

Gaughan, Richard. The Oil Immersion Lens Needed To View Bacteria last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/oil-immersion-lens-needed-bacteria-19559/