Parasitism In The Tundra

The tundra is a cold, sparse environment. Tundras are typically flat areas that have been molded by ice and winter frosts. Tundra biomes lack trees and the plants that do live there have short growing seasons due to the harsh weather, low nutrients in the soil and little precipitation. The arctic tundra has a growing season of a mere 50 to 60 days a year with average temperatures in summer reaching 37 to 57 degrees Fahrenheit.

Types of Symbiotic Relationships in the Tundra

Types of Symbiotic Relationships in the Tundra

There are three main types of symbiotic relationships; parasitism, mutualism and commensalism. A parasitic relationship is when one organism benefits while the other is harmed, or maybe even killed by their interactions. A mutualistic relationship is when both organisms benefit from their interactions. Commensalism is when one organism benefits while the other organism is neither harmed nor benefits.

Parasitic Relationships in the Tundra

Parasitic Relationships in the Tundra

Despite the rough conditions, animals have not been able to escape parasitism in the tundra. Mosquitos (Culicidae), nematodes (Nemathelminthes), lungworms (Strongylida) and ticks (Anactinotrichidea) are common parasites. Though the summer is short, this warmer period allows time for parasite populations to boom. Parasites that live directly on or inside their hosts, like ticks and nematodes, are buffered by the extreme temperatures due to the host's body temperature helping them survive.

Mosquitos

Mosquitos

Mosquitos are common parasites across the globe. While arctic mosquitos don't carry diseases like their tropical cousins, they still cause harm by sucking an animals blood, which also potentially causes lesions. Seeing as there are so few animals in the tundra when mosquitos finally find a host, they can be relentless in their feeding.

The caribou (Rangifer tarandus) or other poor mammal being attacked must cease feeding to thwart their attackers. Researchers have found that this loss of feeding time results in population declines of the mammalian host.

Nematodes

Nematodes

Depending on the species, nematodes, a type of roundworm, can live in the digestive, respiratory or circulatory system of their hosts. Nematodes feed off the fluids or mucosa linings in the host's body. Nematodes typically spread to new hosts through the fecal-oral route. Nematode eggs hatch and develop in feces. Larval nematodes then enter their hosts while they are grazing on vegetation.

Ostertagia gruehneri is a common nematode for caribou and muskox (Ovibos moschatus). Researchers have found that ground temperature, rather than the air temperature, determine the larval nematode developmental time. Field studies revealed that under the right conditions larvae developed in three weeks, just in time for the new calves of the year to start grazing.

Lungworms

Lungworms

Lungworms are a kind of roundworm that lives in the lungs of their host animals. The protostrongylid lungworm, Umingmakstrongylus pallikuukensis, is a common parasite of muskox. This lungworm can reach up to 25.5 inches long. While these lungworms don't directly kill their muskox host, the burden of having parasites on their immune system may make them vulnerable to other diseases.

Like many parasites, U. pallikuukensis require multiple hosts to complete their lifecycle. Larvae hatch in the muskox lungs and crawl into the esophagus so they can exit with the muskox feces. The larvae then penetrate the body of the marsh slug, Deroceras laeve, and continue their larval development. Next, the new unsuspecting muskox host accidentally eats an infected marsh slug while grazing, allowing the lungworm to continue its lifecycle.

Ticks

Ticks

Ticks latch onto their hosts when they sense body heat, movement and vibrations. Ticks drink blood to survive and can cause significant health problems for the host such as anemia or by spreading disease. The winter tick, Dermacentor albipictus, is a problem species for moose (Alces alces) and caribou.

Many of the mammals that live in the tundra are migratory and move south for warmer weather and more food supplies in winter. This migratory behavior can assist the spread of ticks. The ticks latch on in the warmer southern regions then hitchhike north to spread to new animals.

Mutualism and Commensalism in the Tundra

Mutualism and Commensalism in the Tundra

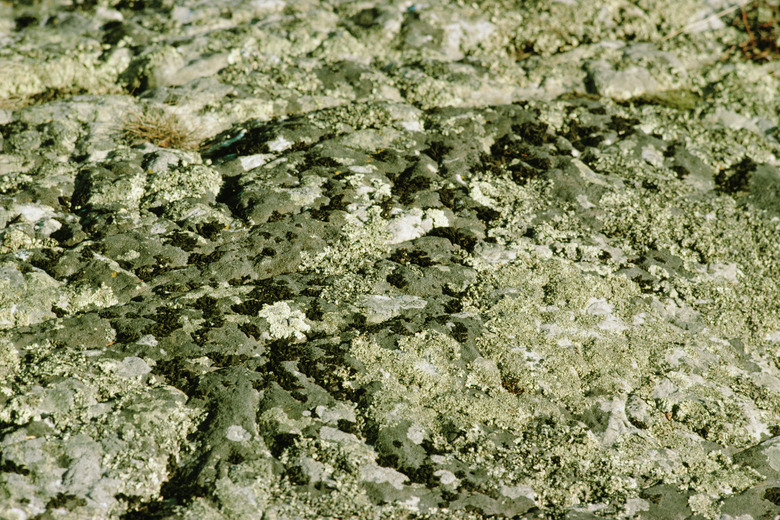

Not all relationships in the tundra have a negative impact. Lichens are an example of mutualism in the tundra. Lichens are not a plant or even a single organism but a combination of fungi and algae or cyanobacteria living as one. With m ore than 500 species in the Arctic, lichens are a vital food source for herbivores in the tundra.

The symbiotic relationship between polar bears (Ursus maritimus) and arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus) can be considered commensalism. Arctic fox will follow polar bears and scavenge on their leftover kills. This interaction doesn't harm the polar bear as they have eaten all that they desire while the arctic fox benefits by getting a meal.

References

- Berkeley: The Tundra Biome

- New England Complex Systems Insitute: Parasitic Relationships

- The Ohio State University: Life in the Tundra

- The University of Utah: Examples of Symbiosis

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention: How Ticks Spread Disease

- Universtiy of Pennsylvania: Parasites and Parasitic Diseases of Domestic Animals

- WWF: Ice Age Relics

- International Journal for Parasitology: A Walk on the Tundra: Host–Parasite Interactions in an Extreme Environment

- National Geographic: Why the Arctic's Mosquito Problem Is Getting Bigger, Badder

- Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology: "Development of the Muskox Lungworm, Umingmakstrongylus pallikuukensis (Protostrongylidae), in Gastropods in the Arctic

- National Parks Service: Lichens of the Arctic

Cite This Article

MLA

Jerrett, Adrianne. "Parasitism In The Tundra" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/parasitism-tundra-4132699/. 31 July 2019.

APA

Jerrett, Adrianne. (2019, July 31). Parasitism In The Tundra. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/parasitism-tundra-4132699/

Chicago

Jerrett, Adrianne. Parasitism In The Tundra last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/parasitism-tundra-4132699/