Relationships Between Mitosis In Eukaryotic Cells And Binary Fission In Prokaryotes

A cell, in the natural world, is the smallest physical unit that manifests all of the properties associates with life itself, such as metabolism (using molecules from the external environment to derive energy for everyday processes such as growth and repair), a well-defined physical container, the maintenance of chemical balance and reproduction.

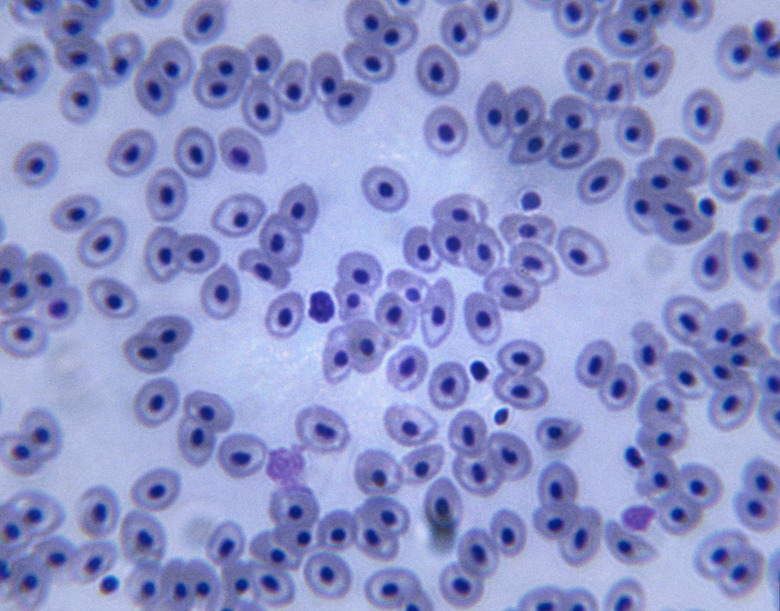

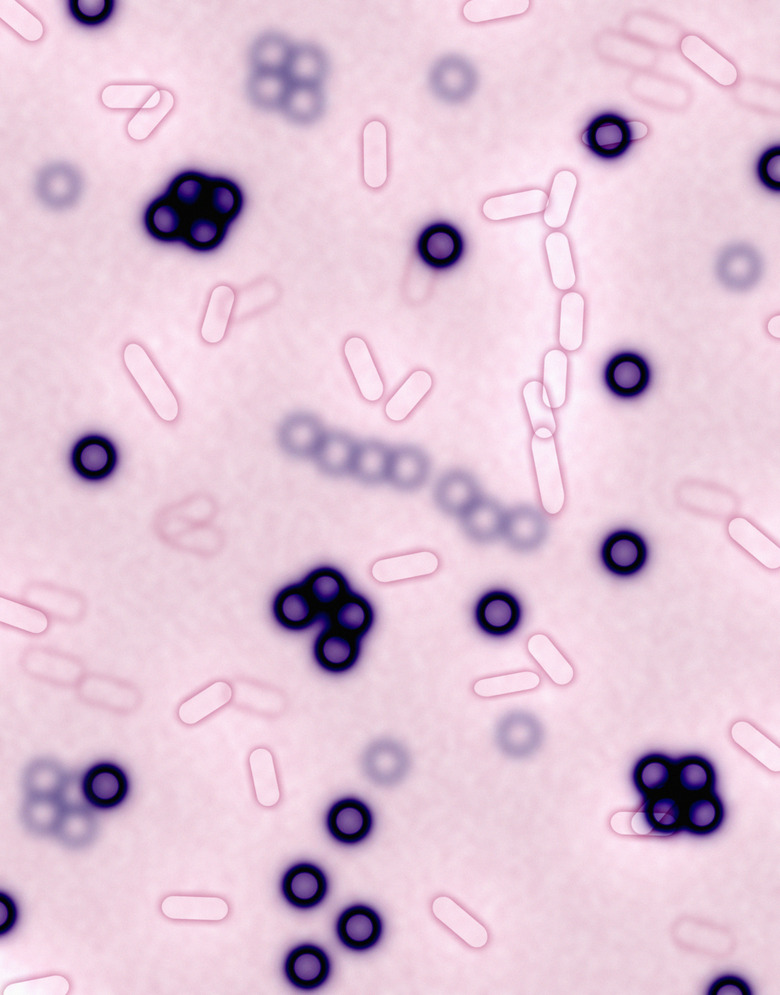

Living things can be divided into _prokaryotes, which are simple, usually one-celled organisms that include bacteria and the organisms in the Archaea domain, and the markedly more complex and diversified eukaryotes_, which are almost all multicellular and include animals, plants, protists and fungi.

The ways that these types of cells reproduce are similar, but very distinct.

Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells

Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells

All cells include four components:

- A cell membrane, also called the plasma membrane, consisting of a phospholipid bilayer.

- Cytoplasm, or cytosol, a gelatinous matrix that provides substance in which other cell components can operate.

- Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), the organism's genetic material.

- Ribosomes, the sites of protein synthesis.

Prokaryotes lack a nucleus, which in eukaryotes holds the DNA and is the site of mitosis, or replication of the genetic material. This genetic material is organized into chromosomes.

Prokaryotic Cell Division

Prokaryotic Cell Division

When prokaryotic cells divide, this, with rare exceptions, implies division of the entire organism and hence reproduction. This process is called _binary fission_, and it's straightforward. It's preceded by an overall enlargement of the cell and its few components, and replication of its DNA, which usually consists of a single ring-shaped chromosome.

When the cell splits in two, the result is two daughter cells that are identical to the parent cell and to each other. This kind of reproduction is asexual, meaning that no change in DNA occurs from generation to generation unless chance mutations, or random alterations, occur.

The Eukaryotic Cell Cycle

The Eukaryotic Cell Cycle

Eukaryotic cells begin their life cycle, also called the cell cycle, in interphase, which includes three phases of its own: _G1_ (first gap), S (synthesis) and _G2_ (second gap). The chromosomes are replicated, or duplicated precisely, in the S phase.

The cell then enters the shortest, but most important, phase: _M phase_, also known as mitosis. This is where the nucleus is divided into two identical daughter nuclei, a process that is immediately followed by the division of the cell itself, or cytokinesis.

Mitosis in Eukaryotes

Mitosis in Eukaryotes

Mitosis can be divided into five phases:

1. Prophase, when the replicated chromosomes become more condensed in the nucleus and the nuclear membrane dissolves. 2. Prometaphase, when chromosomes begin to migrate toward the middle of the cell. (Some older sources omit this stage and divide chromosomal migration between prophase and metaphase.)

3. Metaphase, when chromosomes line up precisely on a line through the middle of the nucleus. 4. Anaphase, when chromosomes are pulled to opposite sides of the nucleus. 5. Telophase and Cytokinesis, when chromosome become less condensed, and nuclear membranes form around the daughter nuclei.

Mitosis is followed immediately by cytokinesis, and the cell cycle begins anew.

Meiosis, the type of cell division that produces sperm cells in males and egg cells in females, is responsible for genetic diversity as it produces non-identical daughter cells. It occurs only in an organism's gonads (testes in males, ovaries in females).

Similarities Between Binary Fission and Mitosis

Similarities Between Binary Fission and Mitosis

Binary fission and mitosis both produce identical daughter cells. Although prokaryotes do not have a cell cycle, both of these processes are preceded by cell growth and adaptations geared specifically toward enabling the division of the genetic material and the entire cell, including replication of the ribosomes.

Binary fission usually occurs very rapidly compared to mitosis. Some E. coli bacteria divide every 20 minutes, whereas a eukaryotic cell cycle may take as long as an entire day.

Cite This Article

MLA

Beck, Kevin. "Relationships Between Mitosis In Eukaryotic Cells And Binary Fission In Prokaryotes" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/relationships-between-mitosis-eukaryotic-cells-binary-fission-prokaryotes-10604/. 9 April 2019.

APA

Beck, Kevin. (2019, April 9). Relationships Between Mitosis In Eukaryotic Cells And Binary Fission In Prokaryotes. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/relationships-between-mitosis-eukaryotic-cells-binary-fission-prokaryotes-10604/

Chicago

Beck, Kevin. Relationships Between Mitosis In Eukaryotic Cells And Binary Fission In Prokaryotes last modified August 30, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/relationships-between-mitosis-eukaryotic-cells-binary-fission-prokaryotes-10604/