How To Tell Male From Female Crickets

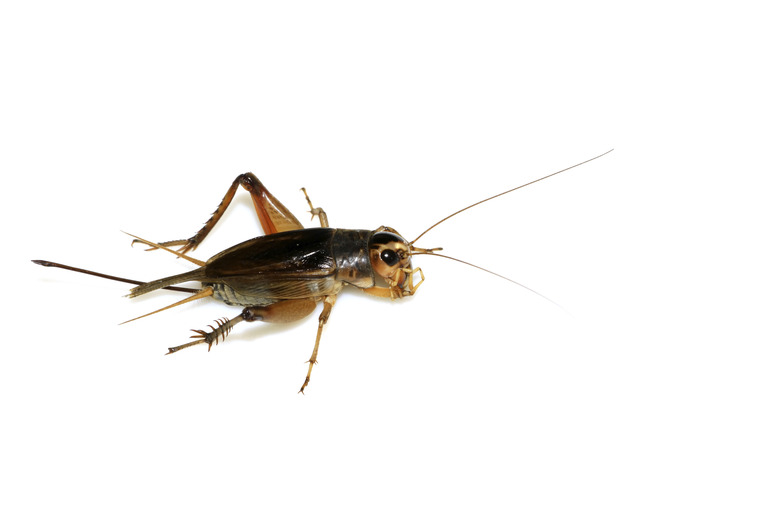

Cricket anatomy is similar to grasshoppers and katydids – all of these insects are members of the order Orthoptera. Orthopterans have chewing mouthparts and three sets of legs, with the back two being longer and stronger to help them jump. Compared to katydids and grasshoppers, crickets' bodies generally appear more flattened and are often brown, but sometimes tree crickets are green with white wings. A key way to tell male and female crickets apart is by looking at their anatomy and listening to their call (or lack thereof).

Male Cricket Calls: Anatomy

Male Cricket Calls: Anatomy

Male crickets use chirping sounds to attract females for mating. They make these chirping sounds by rubbing together specialized structures on their forewings called tegmina. On their forewings, they have a row of teeth on one side, called a file, and on the other a structure called a scraper. Rubbing these together in sequences causes vibrations at different frequencies.

Crickets in the suborder Ensifera have wing cells that capture and transmit the tegminal sounds. The two main types of these wing cells are called harp and mirror. The harp is the largest cell and the main transmitter of sound. Mirror cells are secondary and assist with producing high-frequency noises. Cross-veins that run over the harp and mirror cells also change the frequency of the sound.

Each species of cricket has evolved different structural wing variations to produce distinct calls. However, both male and female crickets have the same earlike structures to hear these sounds called a tympanum. Strangely, cricket's ears are not located where you would expect them to be. Instead of on their heads, their tympanum are on their legs, just below their knee joints.

Male Cricket Calls: Behavior

Male Cricket Calls: Behavior

Some cricket species use holes in leaves or burrows to amplify their calls, making them louder and travel further. For example, male mole crickets from the family Gryllotalpidae are flightless and use their powerful forelegs to dig small burrows in the ground. The male cricket then sits in his chamber, continuously calling at dusk then waiting for a flying female to find him. Unusually among crickets, female mole crickets can also make calling sounds with their wings, but they are quieter than the males.

Female Cricket Ovipositor

Female Cricket Ovipositor

An ovipositor is a long tubular structure located on the posterior of the abdomen that many species of insects use to lay eggs. In crickets, the ovipositor is between two cerci. The cerci look like short antennae and work similarly, helping crickets navigate their environment. Both male and female crickets have cerci, but only a female cricket will have an ovipositor between them. Katydids also have ovipositors, except theirs are flattened while crickets' are rounded.

Female crickets insert their ovipositor into moist substrates, like soil, to lay their eggs in a protected space. Often the length of a cricket's ovipositor in relation to their body varies with the climate they live in. Compared to crickets that live in warmer regions, crickets in cooler areas with long winters tend to have longer ovipositors so they can lay their eggs deeper. One exception to this rule is first-generation female crickets in cooler climates, who have shorter ovipositors than second-generation female crickets. Presumably, this is because their eggs don't have to overwinter, so they don't need to lay them as deep in the soil.

Cricket Nymphs

Cricket Nymphs

Crickets have an incomplete metamorphosis development cycle - this means that after hatching from their eggs, the juveniles, called nymphs, look like small versions of the adults, except they lack genitalia and sometimes wings. As they grow, they repeatedly shed their exoskeleton in a process called molting. The time between each molt stage is termed an instar. It is not until they reach their later instar and adult stages that male and female crickets are easily differentiated.

Cite This Article

MLA

Jerrett, Adrianne. "How To Tell Male From Female Crickets" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/tell-male-female-crickets-7692270/. 30 September 2021.

APA

Jerrett, Adrianne. (2021, September 30). How To Tell Male From Female Crickets. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/tell-male-female-crickets-7692270/

Chicago

Jerrett, Adrianne. How To Tell Male From Female Crickets last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/tell-male-female-crickets-7692270/