Why Are There Buffers In Fermentation?

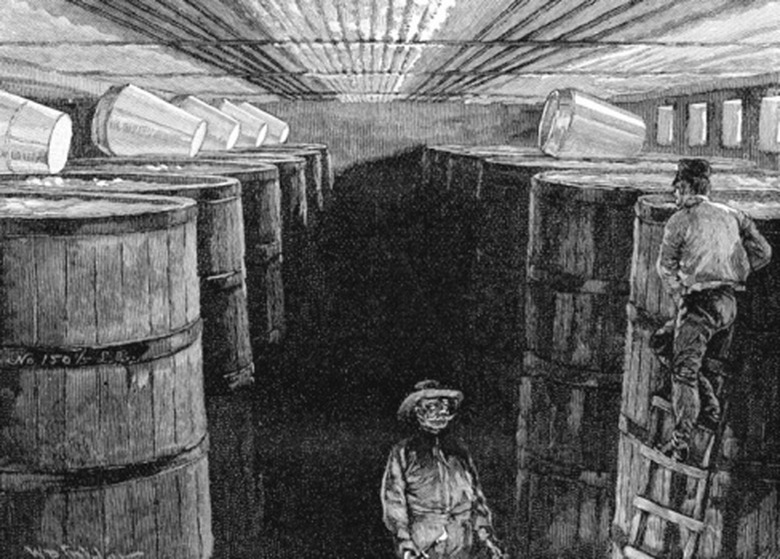

Humans have used ethanol — in wine, beer and other alcoholic beverages — as a recreational drug since prehistory. More recently, ethanol has also become important as an alternative fuel. Whether for human consumption or combustion in cars, ethanol is produced using yeast, microbes that ferment sugars and release ethanol as a waste product. Buffers are added during this process to help stabilize the pH.

pH

pH

Maintaining stable pH or hydrogen ion concentration is crucial to obtaining a good yield from fermentation. That's because the yeast that ferment the sugars are living organisms, and their biochemistry only functions well within a certain pH range, just like yours. If you were dunked in a bath of sulfuric acid, for example, it would either kill you or injure you badly. The same holds true for the yeast: if the pH is so high or low that it falls outside their tolerance range, it could inhibit their growth or even kill them.

Carbon Dioxide

Carbon Dioxide

The fermentation process in the yeast bears some similarities to the fermentation process that takes place in your muscle cells when they are short on oxygen — when you are sprinting, for example. Your cells release carbon dioxide and lactic acid from fermentation; yeast, by contrast, release carbon dioxide and ethanol. That carbon dioxide, in fact, is why you use yeast to make bread rise; the trapped gas creates expanding bubbles in the dough.

Carbonic Acid

Carbonic Acid

In a fermentation vat, the concentration of CO2 in the solution is higher than normal due to the fermentation activity. Much of this excess CO2 bubbles off. It also acidifies the solution, however, because dissolved CO2 combines with water to create carbonic acid. If the solution became too acidic, it could inhibit yeast growth. Yeast prefer a pH in the 4 – 6 range, so bakers, brewers and other industries relying on fermentation use buffers to keep the pH within an optimal range.

Function of Buffers

Function of Buffers

As the pH rises, the rate at which the buffer compound loses hydrogen ions (protons) increases, and although more of the buffer compound has lost its protons, the pH of the solution only changes slightly. When the pH falls, the reverse process occurs; a larger fraction of the buffer molecules have accepted protons, and again the buffer moderates the change in pH. Basically, the buffer compound helps to "soak up" excess acidity or alkalinity. The pH will only start to change significantly once most of the buffer compound has been neutralized or "used up."

References

- Handbook of Food Science, Technology and Engineering: Fermentation, Principles and Microorganisms

- Biomass Handbook: Industrial Fermentation of Ethanol

- Dakota Yeast: Fermentation of Baker's Help

- "Chemical Principles: The Quest for Insight"; Peter Atkins, et al.; 2008

Cite This Article

MLA

Brennan, John. "Why Are There Buffers In Fermentation?" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/there-buffers-fermentation-8377513/. 24 April 2017.

APA

Brennan, John. (2017, April 24). Why Are There Buffers In Fermentation?. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/there-buffers-fermentation-8377513/

Chicago

Brennan, John. Why Are There Buffers In Fermentation? last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/there-buffers-fermentation-8377513/