Tools Used By Early Explorers

It's hard to imagine going anywhere today without a GPS unit, a PDA or at least directions from a reputable map, but early explorers did it without modern equipment as they courageously forged their way to uncharted lands. Despite the fact that exploration was often prompted by a lust for gold or riches, or to conquer people and acquire land, often in the name of religion, early explorers nevertheless used tools that were state-of-the-art at the time, but now seem crude compared to the electronic devices available in the 21st century. Read on to learn more about the tools early explorers used.

Stars and the Astrolabe

Stars and the Astrolabe

Phoenician explorer-navigators sailed from the Mediterranean along the coast of Europe and Africa, keeping land in their sights. If they ventured further out to sea, they relied on the "Phoenician Star," now known as Polaris, to guide them. In the event that the stars were obscured by clouds and bad weather, they opted to head back to the safety of land. The astrolabe was invented later, possibly by the Greeks around 200 B.C.E., and was initially used by astrologers and astronomers to "take a star" when measuring angles and altitude of the Sun to establish latitude. Using an astrolabe to fix location required a clear view of the horizon and a steady hand. Unfortunately, when used aboard ships, the rolling of the seas and pitching of a ship could result in erroneous readings and measurements.

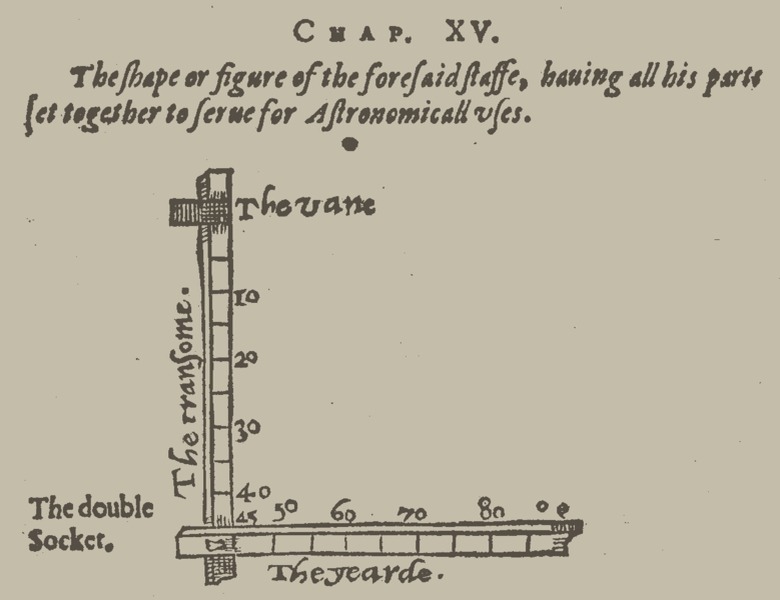

Cross-staffs and Back-staffs

Cross-staffs and Back-staffs

The cross-staff was a simple instrument used for measuring the distance between Polaris and the horizon. It was basically two wooden pieces, one long and one a much shorter cross-piece. The longer section was marked off by a graduated scale that measured how high the sun or Polaris was in the sky. Two major drawbacks of the cross-staff were that the explorer had to stare directly into the sun to use it and was blinded, and the device was virtually useless in cloudy weather. Also, a rocking ship interfered with the accuracy of any measurements taken. In the late 16th century, John Davis invented the back-staff, which was used with the observer's back to the sun. By sighting the horizon, the sun was reflected onto a horizontal slit made of brass, and by making adjustments to the sliding vane, more accurate altitude and latitudinal measurements could be made.

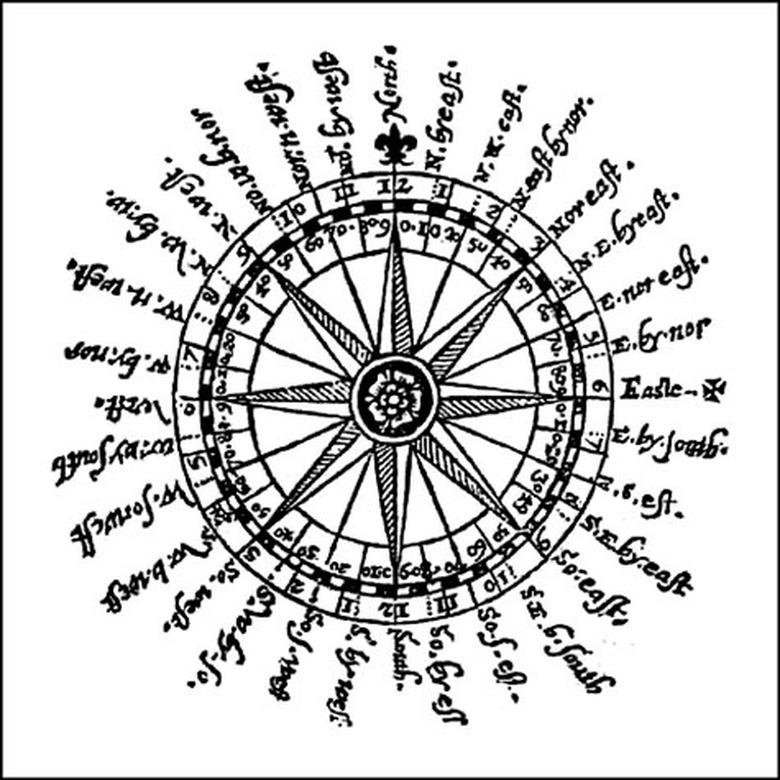

Lodestones and Compasses

Lodestones and Compasses

One of the first ways explorers located north was to use a lodestone, a magnetic rock suspended on a string or poised on a piece of wood. Sometimes needles were magnetized by a lodestone and hung on a string to indicate true north. Eventually, the Venetians devised a compass that indicated the four directional points and used a magnetized needle. Explorers on land and sea began using compasses, which were a fairly reliable means of finding direction, except when land masses interfered with the needle's magnetic properties. Navigators needed to know not only the direction they were heading, but how fast they were traveling in order to estimate where they were. So, in combination with the compass, explorers at sea used a chip log, a floating board on a knotted rope, that they tossed overboard, and made calculations on their ship's speed by timing how long it took to reel in the board and measuring how much rope had been reeled out.

Sandglasses and Chip-logs

Sandglasses and Chip-logs

Around the 10th century A.D., the sandglass, or hourglass, was invented to mark the passage of hours. Early explorers, especially those at sea, needed to mark not only the length of their watches, but also the time it took to reel in and out the rope attached to the chip log. Sandglasses, most often filled with pulverized shells, marble or rocks instead of sand to avoid clumping, measured different increments of time, usually an hour, but 30-second sandglasses were also needed for timing the chip-log.

The Quadrant Device

The Quadrant Device

Another simple device used by early explorers from medieval times on for measuring altitude and latitude was the quadrant. The quadrant was a quarter-circle wedge of wood or metal with a scale of 0-90 degrees marked along its outer edge. A rope or string weighted on one end with a plumb bob hung down from the tip of the quadrant; an explorer or navigator looked through a small pinhole in the center, sighted the sun or star, and read the degree indicated by the plumb bob. The height of large objects, mountains or hills could be determined using a quadrant, as well as the angle of the sun or Polaris.

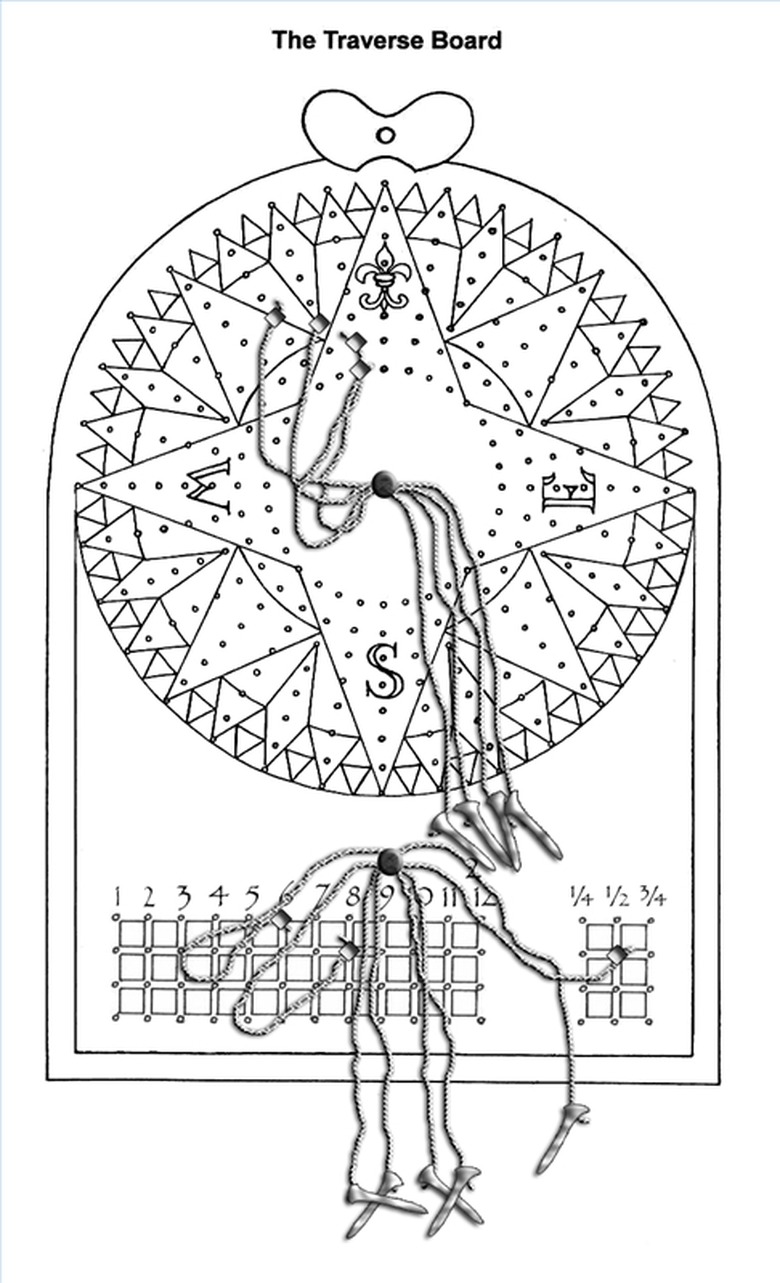

The Traverse Boards

The Traverse Boards

Probably invented some time during the 1500s, traverse boards were used in navigation and early exploration to record all the information gathered from a sailor during his four-hour watch. The board kept track of how far the ship had traveled, the direction it had been heading, and the speed it had made. The wooden traverse board used a system of holes and pegs for the user to indicate these points over a four-hour period of time, so that at a glance anyone else on the ship could know what had transpired. At the end of the watch, the information was transferred and given to the captain of the ship, who then transferred it to the ship's log at the end of each day. Using the information gathered on the traverse boards, the navigator aboard ships could track the progress of the sea journey on any maps available to him at the time.

Cite This Article

MLA

Osborne, Mary. "Tools Used By Early Explorers" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/tools-used-early-explorers-5389774/. 23 April 2018.

APA

Osborne, Mary. (2018, April 23). Tools Used By Early Explorers. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/tools-used-early-explorers-5389774/

Chicago

Osborne, Mary. Tools Used By Early Explorers last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/tools-used-early-explorers-5389774/