The Topography Of Deserts

Topography plays an influential role in the formation of deserts: many of the world's great drylands form downwind of formidable mountain barriers, their aridity deriving from the uplift's rain shadow. The terrain map and elevation of deserts can be quite varied, from vast cobble flats to mobile dune seas, and from bone-dry arroyos to lofty mountains.

Read more about abiotic factors of a desert ecosystem.

Desert Flats

Desert Flats

Many of the world's deserts exhibit vast swaths of flat or gently rolling country cloaked in sparse vegetation. This type of elevation in deserts may derive from any number of geologic processes.

The flat valleys of the Great Basin of North America, which encompasses the majority of the continent's true deserts, derive from extensive faulting and are separated by corresponding parallel mountain ranges. The "regs" of the Sahara Desert are windswept gravelly flats.

In some elevation of deserts, as in some of the drier portions of the Sonoran Desert, a so-called "desert pavement" covers level terrain, comprised of tightly packed, relatively even stones. Such pavements are believed to form over great periods of time as wind action forces fine dust under surface stones, where it accumulates and gradually elevates the cobble above the underlying bedrock.

Mountains and Hills

Mountains and Hills

The planet's deserts exhibit notable relief. Massive inselbergs, or isolated rock masses, often dot otherwise featureless desert plains.

The Brandberg, loftiest summit in Namibia, looms as a granite island from Namib Desert flats, for example. Layers of durable rock may resist erosion much longer than more yielding substrates, forming flat-topped buttes and mesas as outliers. In the fault-block deserts of North America's Great Basin, lofty north-south mountain ranges can exceed 12,000 feet in elevation.

Erratic drainage of such desert uplifts form alluvial fans at their flanks, as occasional torrents pile rubble at the mouths of valleys. A series of alluvial fans that coalesce into a large, sloping pedestal fringing the mountains form what are called "bajadas." High mountains within desert biomes often create isolated zones of cooler temperatures and far greater precipitation, allowing for the development of forests and grasslands that form a striking contrast with the sere lowlands.

Watercourses

Watercourses

The surface drainage of deserts can be limited or nearly non-existent. Streams may be dry for months or years. The sculpting of landscape by moving water, therefore, is often limited to the action of brief bouts of heavy rainfall.

Bleak, often steep-edged watercourses that are dry for much of the year are common to arid deserts and go by any number of regional names: "wash" or "arroyo" in the U.S. Southwest and Mexico, "wadi" in North Africa, "nullah" in India. These steep-edged features are easily spotted on a terrain map.

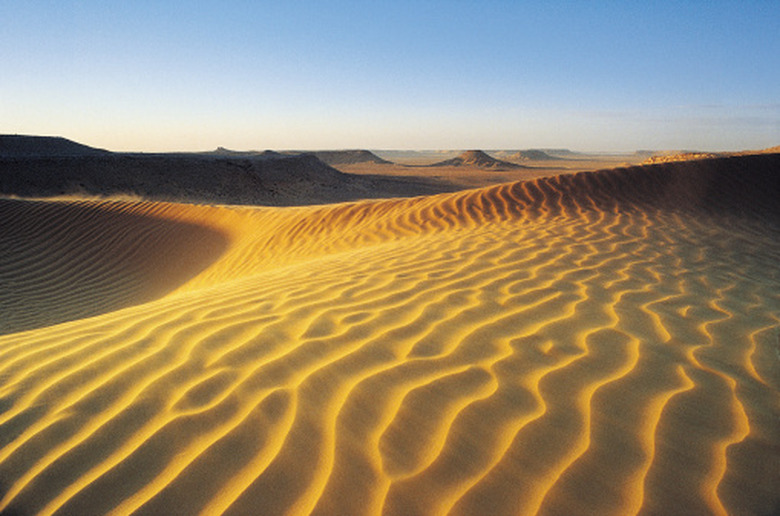

Dunes

Dunes

Prevailing winds may render tracts of deserts into open sand in areas where precipitation and groundwater are too scanty for vegetation development. Dunes commonly accumulate on the windward edge of uplifts, downwind of sand reservoirs like ephemeral watercourses and lakebeds. Massive, ever-shifting dune seas, called ergs, are some of the most striking topography in deserts like the Sahara, the Namib, the Arabian and the Simpson in Australia.

A big erg exists in North America's Sonoran Desert, covering much of the El Gran Desierto section. The interaction of terrain and wind creates numerous kinds of dunes (as you can see on many terrain maps), from crescent-shaped barchans to radiating star dunes.

Read more about how to make sand dunes for a school project.

References

- "A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert" (Phillips, Comus eds.); Desert Soils; Joseph R. McAuliffe; 2000

- PBS – Africa: Explore the Regions – Sahara

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration: ASTER – Brandberg Massif

- "Deserts"; James A. MacMahon; 1997

- "A Dictionary of Geography"; W.G. Moore; 1968

- "Cactus Country"; Edward Abbey; 1973

Cite This Article

MLA

Shaw, Ethan. "The Topography Of Deserts" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/topography-deserts-8178249/. 22 November 2019.

APA

Shaw, Ethan. (2019, November 22). The Topography Of Deserts. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/topography-deserts-8178249/

Chicago

Shaw, Ethan. The Topography Of Deserts last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/topography-deserts-8178249/