Two Types Of Cilia In A Paramecium

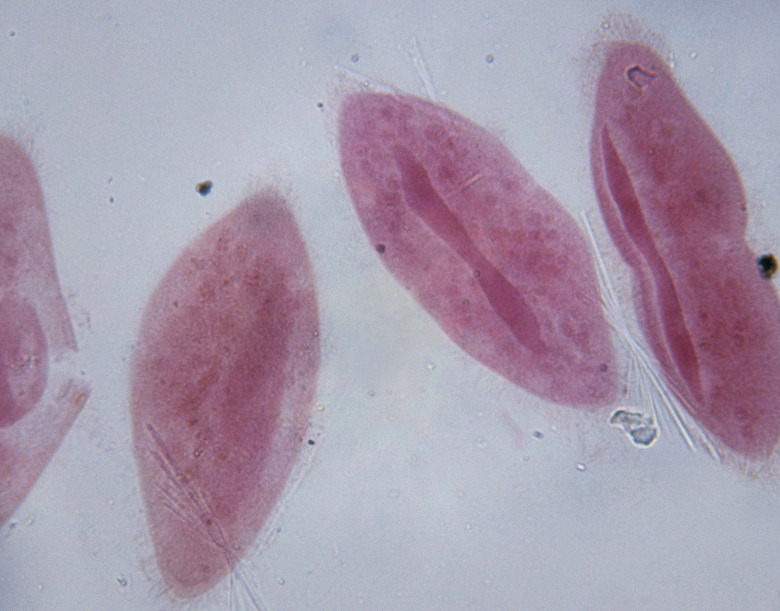

Paramecia are single-celled microorganisms that live in freshwater and marine environments. They belong to the phylum Ciliophora, the ciliated protozoa. A cilium is a short, hair-like structure that protrudes from an organism's cell membrane. A paramecium has thousands of cilia that rhythmically beat, providing a way for it to move around and to sweep food into its oral groove. Scientists have discovered that different biochemical motors power the cilia function in the paramecium.

My Little Paramecium

My Little Paramecium

Paramecia come in many species and range in length between 50 and 330 micrometers — roughly one-thousandth to one-hundredth of an inch. The cell membrane, or pellicle, is covered throughout with cilia. Paramecia eat bacteria, algae and other tiny creatures by ingesting them via a cilia-covered oral groove that runs from the front of the cell to the midpoint. The paramecium swims around by beating its cilia in unison, but the cilia surrounding the oral groove beat to a different rhythm.

Cilium Structure and Types of Cilia

Cilium Structure and Types of Cilia

The structure of a cilium is a bundle of microtubules, known as an axoneme, that is attached to a basal body on the cell surface. A microtubule is composed of about 13 protofilaments, long cylinders that align side by side to form the microtubule's hollow tube shape. An axoneme contains nine outer pairs of double microtubules and two central singular microtubules. Various bridges connect the members of both microtubule arrays and connect the two arrays to each other. Proteins known as molecular motors cause cilia to beat.

Molecular Motors

Molecular Motors

A cilium beats because certain molecular motors change shape. The motors draw energy from adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, the universal energy storage biochemical. When a chemical reaction liberates a phosphate group from ATP, the molecular motors within the connecting bridges between axonemes pivot. The result is that one microtubule moves relative to another and pull cilia into motion. While the cilia structures that propel a paramecium are identical to the structures that sweep food into its mouth, the two actions use different molecular motors and operate at different frequencies and strengths.

Experimental Evidence

Experimental Evidence

In 2013, researchers at Brown University led by graduate student Ilyong Jung manipulated the viscosity of the liquid surrounding paramecia. Starting with water, they increased the density of the liquid up to seven-fold. They found that higher viscosity slowed down the swimming cilia but hardly affected the feeding cilia. Doubling the viscosity cut the swimming action by about half, but even with a seven-fold increase, the feeding cilia slowed down by only about 20 percent. Because all the cilia share the same structure, only a difference in the molecular motor can account for the results. Work continues to determine the exact underlying mechanisms.

Cite This Article

MLA

Finance, Eric Bank, MBA, MS. "Two Types Of Cilia In A Paramecium" sciencing.com, https://www.sciencing.com/two-types-cilia-paramecium-18998/. 6 August 2018.

APA

Finance, Eric Bank, MBA, MS. (2018, August 6). Two Types Of Cilia In A Paramecium. sciencing.com. Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/two-types-cilia-paramecium-18998/

Chicago

Finance, Eric Bank, MBA, MS. Two Types Of Cilia In A Paramecium last modified August 30, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/two-types-cilia-paramecium-18998/